Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news organization covering public education in communities across America. Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to keep up with NYC’s public schools.

New York City’s elementary schools will be required to use one of three reading curriculums, a tectonic shift that education officials hope will improve literacy rates across the nation’s largest school system.

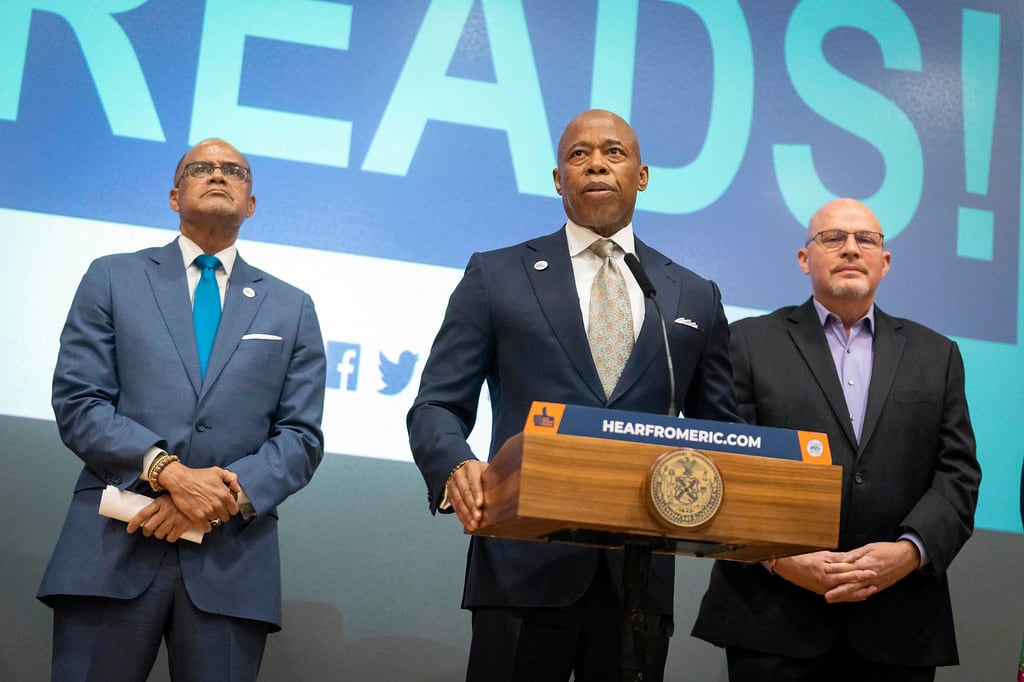

Beginning in September, elementary schools in 15 of the city’s 32 districts will be required to use one of three programs selected by the education department, Chancellor David Banks and Mayor Eric Adams announced Tuesday. By September 2024, all of the city’s roughly 700 elementary schools will be required to use one of the three. Chalkbeat first reported the plans in March.

The new mandate won support from the teachers union, whose leaders expressed faith in the city’s efforts to train thousands of teachers on new materials. Training for the first year is expected to cost $35 million, though city officials declined to provide an estimate of the effort’s overall price tag, including the cost of purchasing materials.

Meanwhile, the plan earned a strong rebuke from the union representing principals, who have long had wide latitude to choose which materials their teachers use. That freedom has allowed school leaders to use programs that vary widely in their approach and quality, Banks has argued.

The chancellor has frequently called for a more systematic approach, citing lagging reading scores. About half of the city’s students in grades 3-8 are not considered proficient readers based on state tests. The results are even more stark among certain subgroups: Fewer than 37% of Black and Latino reached that threshold and the numbers significantly are lower for students with disabilities and those still learning English.

“They aren’t reading because we’ve been giving our schools and our educators a flawed plan,” Banks said during the announcement at Brooklyn’s P.S. 156. He added: “It is really an indictment on the work that we do.”

Now, city officials will require one of three reading programs: Wit & Wisdom, from a company called Great Minds; Into Reading from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; or EL Education. They charged superintendents of each district to select their schools’ curriculum. Thirteen of the initial 15 districts are planning to use Into Reading. Some schools are already using these curriculums, and city officials did not say how many will have to switch.

All three curriculums have met quality expectations set by EdReports, an independent curriculum reviewer. And they also met the group’s standards for helping students build background knowledge by exposing them to more content in topics like science and social studies, something many experts say is an important ingredient for building reading comprehension skills.

But some of the curriculum materials have also faced criticism. A review from New York University found that Into Reading is not culturally responsive and “used language and tone that demeaned and dehumanized Black, Indigenous and characters of color, while encouraging empathy and connection with White characters.”

Asked about those findings, Deputy Chancellor Carolyne Quintana pointed to the education department’s own culturally responsive materials that can supplement the other reading programs “to better reflect the range of ethnicities and cultures that we have here in New York City.”

The new initiative builds on previous efforts to bolster literacy instruction, including a requirement that schools use city-approved phonics programs, which help students master the relationship between sounds and letters. Education officials have also launched programs to reach students with dyslexia, including a standalone school dedicated to students with reading challenges that will launch in the fall.

Adams, who has repeatedly pointed to his own struggle with dyslexia in school as a motivation for improving literacy instruction, acknowledged that the city’s efforts will take time to come to fruition, likely stretching beyond his administration.

“Is it going to be perfect? No,” the mayor said. “But dammit, we’re going to try.”

Retraining teachers in the shift from ‘balanced literacy’

City officials are pushing schools to move away from a framework known as “balanced literacy” which places a greater emphasis on exposing students to books of their choice to help them develop a love of reading rather than explicit instruction on foundational reading skills.

Balanced literacy was pushed into schools in 2003 under Chancellor Joel Klein and has enjoyed support from successive school chancellors.

But even as a growing chorus of experts have pointed to research showing the importance of teaching foundational reading skills, a balanced literacy program written by Lucy Calkins at Teachers College has remained in hundreds of elementary schools in recent years, an investigation by Chalkbeat and THE CITY found. (Calkins has revised her materials to include more of an emphasis on phonics.)

Many advocates felt relieved when Banks took the helm of city schools and issued a blunt assessment of balanced literacy and Calkins materials, arguing the approach “has not worked.” And literacy experts have widely cheered the city’s plans to mandate a smaller set of reading choices, effectively preventing schools from using balanced literacy programs like the one written by Calkins.

But a new curriculum alone is unlikely to dramatically improve student learning. Much of the plan will hinge on how effective the city’s training is and whether educators buy in to the changes. Meanwhile, curriculum shifts often take years to execute, and there is little time to train thousands of teachers who will be expected to transition to new materials beginning in September.

Education department officials are gearing up training efforts and will pay teachers extra this summer and during the school year to help them prepare, though it’s unclear how much training most teachers will receive before the rollout begins. They also noted each school will have access to more than three weeks worth of training and teachers will receive “job-embedded coaching.”

Michael Mulgrew, president of the teachers union, said he’s seen the city’s training plans come into focus in recent weeks and lent his support, flanking Adams and Banks during the announcement.

“It’s all hands on deck — everybody has to work together,” Mulgrew said in an interview, though he noted that many of his members are “pessimistic” about being forced to adopt new materials. “It should have never been a school system where every school was left on their own to do whatever they want.”

Having fewer curriculums will make it easier to provide teacher training, proponents of the change argue, since superintendents can focus on supporting schools with one curriculum instead of a hodge-podge. And if students switch schools, particularly students who live in temporary housing, they’ll be much less likely to start from scratch with a new program.

“Right now professional learning is like random skills led by fly-by providers,” said Evan Stone, executive director of Educators for Excellence, a teacher advocacy group that has pushed for more standardized curriculums. “Now teachers can become true experts in a core set of tools.”

Principals union worries about buy-in from schools

Still, the changes have met resistance from the city’s principal union, whose members’ freedom to choose instructional materials will be curtailed. And some educators have also expressed frustration that they will no longer be able to use approaches that they believe are working for their students. Other veteran educators have seen education initiatives ebb over time and worry they’re being asked to make a change that will ultimately be scrapped in a few years.

Henry Rubio, president of the Council of School Supervisors and Administrators, issued a statement criticizing the department for its lack of outreach in developing its plan, saying that his union repeatedly asked why city officials did not engage parents, teachers, and principals on the shift.

With superintendents choosing their district’s curriculum without giving schools a chance to evaluate them, Rubio cast doubt on whether the move will “earn essential buy-in within their communities.” He also worried that the timeline was too short for many principals, who have been focused on end-of-year activities and planning for summer school.

“This is a massive overhaul of how we teach children to read, and the DOE has provided little detail on how thousands of educators will be adequately trained by September,” Rubio said. “Perhaps more importantly, why have half the districts been given well over a year to adequately prepare while the other half are forced to rush through this vital training?”

Education department officials said there may be some exemptions to the mandate, but emphasized that they will be limited in scope and only apply to a small number of schools.

Some teachers are hoping their schools will qualify for exemptions. At P.S. 236 in the Bronx, the school has been transitioning to Wit & Wisdom from Calkins’ balanced literacy curriculum called Units of Study. Teachers there have been learning how to implement the new lessons, which include more difficult texts and less independent reading time when students read books of their choosing.

And while the school is not in the first wave of those expected to change curriculums, they worry that they’ll be forced to start fresh with a new program depending on what their superintendent selects for their district, even though they’re already using one of the city’s approved programs.

“That would be a lot of work and a lot of wasted effort,” said Susan Mackle, a second grade teacher.

The city is also planning to require more standardized curriculums in other parts of the system. About 178 high schools will begin using a standardized algebra curriculum called Illustrative Math. And early childhood programs will be expected to use a program called The Creative Curriculum.

Amy Zimmer contributed.

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.