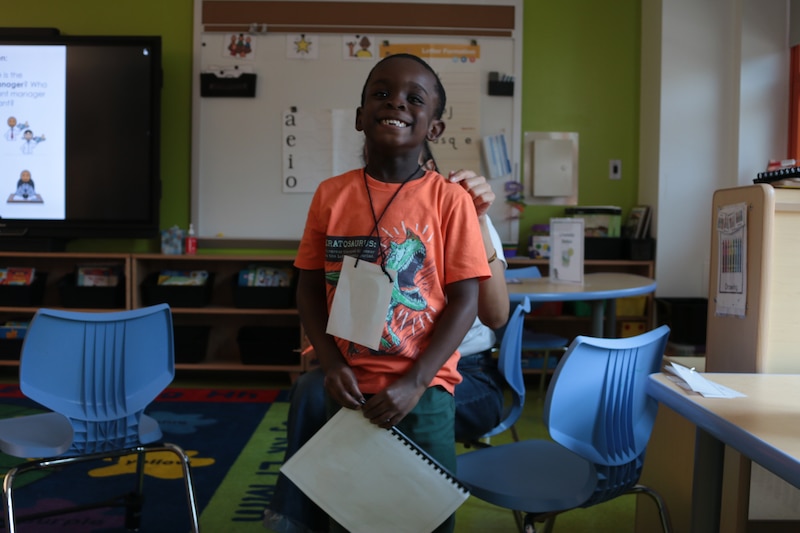

Outfitted with paper chef hats, a group of students at Brooklyn’s P.S. 958 were getting ready on a recent afternoon to launch a mock restaurant, wiggling on the classroom carpet in anticipation of their first wave of customers.

The students had been preparing since February, touring their surrounding Sunset Park neighborhood to learn what types of food were most prevalent before settling on a Mexican theme. The 3-, 4-, and 5-year-olds also studied different roles within a restaurant — including chef, host, server, and manager — before assuming one of those positions themselves.

It was no traditional end-of-year project for the school, which is wrapping up its inaugural year. As the students scampered to their stations and loaded up plastic trays of popcorn and water, the moment represented a test of the new school’s unusual mission: to serve any student in the surrounding neighborhood — ranging from typically developing children to those with more significant disabilities — and meaningfully integrate them in classrooms and other activities whenever possible.

All of the mock restaurant’s customers, who soon began trickling in, were students with autism from a neighboring classroom whose needs would have otherwise landed them in a separate school for students with more complex disabilities.

All city elementary schools are required to accommodate students with disabilities, but some 26,000 children attend District 75 programs, a citywide network of schools that exclusively serve students with more serious needs. Inconsistent or inadequate special education services have also helped drive thousands of additional families to private schools with tuition financed by the city, which involves a complex legal process that favors those with time and resources.

P.S. 958, however, is trying to keep children who may have higher needs closer to home, something a group of caregivers in Sunset Park have long pushed for. The school’s mission is in line with an effort by schools Chancellor David Banks to expand programs designed to include students with disabilities alongside their typically developing peers, part of a push to keep families from exploring private options.

P.S. 958 is wrapping up its first school year — serving 3- and 4-year-olds in prekindergarten, as well as kindergarten, in its own gleaming new building on Brooklyn’s Fifth Avenue. It will gradually expand to fifth grade in the coming years.

About half the school’s students have disabilities, more than double the citywide rate. A majority of the school’s students come from the surrounding neighborhood, and the school prioritizes local applicants in its admissions process, officials said, though some local parents said they hope the city does more to get the word out.

Emily Shapiro, the principal of P.S. 958, spent 20 years working in District 75, starting as a paraprofessional right out of high school. Those schools often provide crucial support that traditional elementary schools don’t offer, she said. But the students who attend often have to travel far outside their neighborhoods, which can make it difficult to forge bonds with other children in the neighborhood and attend after-school programs, and it can lead to lost instructional time thanks to the city’s notoriously unreliable yellow bus system.

“Once the kids leave the school building, they don’t see each other at the playground, or at the grocery store. Parents aren’t building relationships,” Shapiro said, adding that siblings typically can’t attend school together if one of them is placed in District 75. “The idea of being able to go to school in your neighborhood, that’s the number one most important piece of all of this.”

A new model for integrating students of all abilities

One way the school is working to include a more diverse group of students is by hosting programs that are more typically found in schools that only cater to students with disabilities. P.S. 958, for instance, is the first elementary school outside District 75 to host an AIMS program, short for Acquisition, Integrated Services, Meaningful Communication, and Social Skills.

The AIMS program is designed for students with autism who have significant behavioral, communication, or social delays. It involves small group instruction and a bevy of dedicated staff, including a certified behavior specialist, special education teacher, speech teacher, and paraprofessional.

In a traditional District 75 program, those students might have more limited contact with their typically developing peers. At P.S. 958, they were the first set of customers to test out the mock restaurant their classmates next door were setting up.

As they filtered into the classroom, the AIMS students largely needed assistance from classroom aides and iPads with picture-to-speech software to communicate snack orders. But the interactions let them practice conveying their needs, and the students running the restaurant were also learning how to work with peers who may not pick up on typical social cues, such as making eye contact.

P.S. 958 is starting small, enrolling 59 students in its first year — including six in the AIMS classroom. As the school grows to serve students from 3-K through fifth grade in the coming years, the school plans to grow the AIMS program, too.

To be sure, some District 75 schools, which often share buildings with other schools, also give students opportunities to interact with their typically developing peers, such as shared physical education classes or sports teams.

But frequent opportunities for meaningful inclusion are rare, especially when it comes to academics, according to educators and advocates. There are often signals that inclusion isn’t a priority: District 75 students can be forced to use separate entrances to school buildings or may struggle with equal access to school facilities.

There can also be downsides to segregating children with more intensive needs. Some families and educators say those programs can be chaotic or may represent little more than holding grounds, especially for children with more intense emotional or behavioral issues. Still, it can be difficult to tease out the impact of inclusive classrooms and it may not always be effective for students with disabilities to learn in general education classrooms.

Some observers said the P.S. 958 model is promising and stressed that the city should do more to get the word out about schools that have inclusion programs.

“What you really want is [P.S.] 958’s everywhere,” said Jenn Choi, an advocate who helps families navigate the city’s special education system, noting that meaningful inclusion is rare.

“Inclusive doesn’t mean ‘I let you in here.’ Inclusive means ‘I’m going to help you when you’re here,’” she said. “I don’t hear that message very often.”

So far, about 15% of students enrolled at P.S. 958 likely were initially recommended for more restrictive settings than what the school offered — such as those with very small class sizes and intensive support that can be offered through District 75. And while Shapiro said the school is not yet equipped to handle any student who might want to enroll, they’ve had success working with families who were initially slated for more specialized programs but wanted to give P.S. 958 a shot.

Commitment to inclusion runs throughout the school

Fahyolah Antoine, a special education teacher who helped plan the mock restaurant project, said she’s been impressed with the school’s commitment to inclusion. “What I really appreciate is how special education is put on the forefront, rather than the backburner,” she said. “Sometimes it can just feel like it doesn’t get the attention it needs and deserves.”

For example, students from the AIMS program may participate in academic programs with their peers in other classrooms. In one instance, the school placed a less verbal student in a classroom with more verbal students for phonics — lessons that teach children the relationships between sounds and letters.

“Because the other students are saying, ‘A-Apple-Ah,’ and using their voice, he’s starting to do it,” Shapiro said. “Putting him in a classroom with other peer models, who are using those skills is more motivating, I think, than having a speech therapist sitting next to you” practicing the same lesson.

Staff are also intentional about grouping students of different ability levels for other activities, like recess and music. Students also do not sit with their regular classes during lunch, giving students of a wider range of ability levels the chance to interact with each other.

Parent Ivelisse Castro said those types of interactions have been a big help for her daughter, Chloe. The 3-year-old, who has a learning disability, struggled to coordinate her movements without falling down, and she often screamed or whined rather than using words to articulate her feelings.

In Chloe’s pre-K classroom, which includes children with and without disabilities, “she’s picking up habits from them, how to express herself better, how to speak better,” Castro said. “She can have a conversation with you now — it’s an amazing feeling.” She was relieved to find a school that could meet Chloe’s needs just down the block from her home.

The school also makes time for service providers such as speech and occupational therapists to regularly consult with teachers. Through a creative scheduling arrangement, therapists conference with educators multiple times a week, eventually discussing each of the school’s students — including those without disabilities.

They’ve collaborated on issues such as deploying adaptive seating for students who struggle to focus in traditional classroom chairs. (The school also has a dedicated space where students with sensory issues can receive extra help.)

“In other schools, there isn’t structured time for this,” said Cara Kantrowitz, an occupational therapist. “Here, it’s built into everyone’s schedule.”

Back at the mock restaurant, the mood at times resembled the frenetic energy of a professional kitchen, as one child was momentarily overwhelmed with orders.

“I need servers! I need servers!” he shouted. “I need their popcorn!” With plenty of adults on hand to keep students on track, the popcorn orders made their way back to the tables on small paper plates.

Antoine, the special education teacher, noted that the students running the mock restaurant also include a mix of students with and without disabilities. The teachers worked to let students tap into their strengths and interests in deciding what roles to take on.

After students had a chance for seconds, it was time for the next class period. As a handful students from the AIMS classroom filed out, the children running the mock restaurant offered a sendoff.

“Thank you — come again!”

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.