Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to keep up with NYC’s public schools.

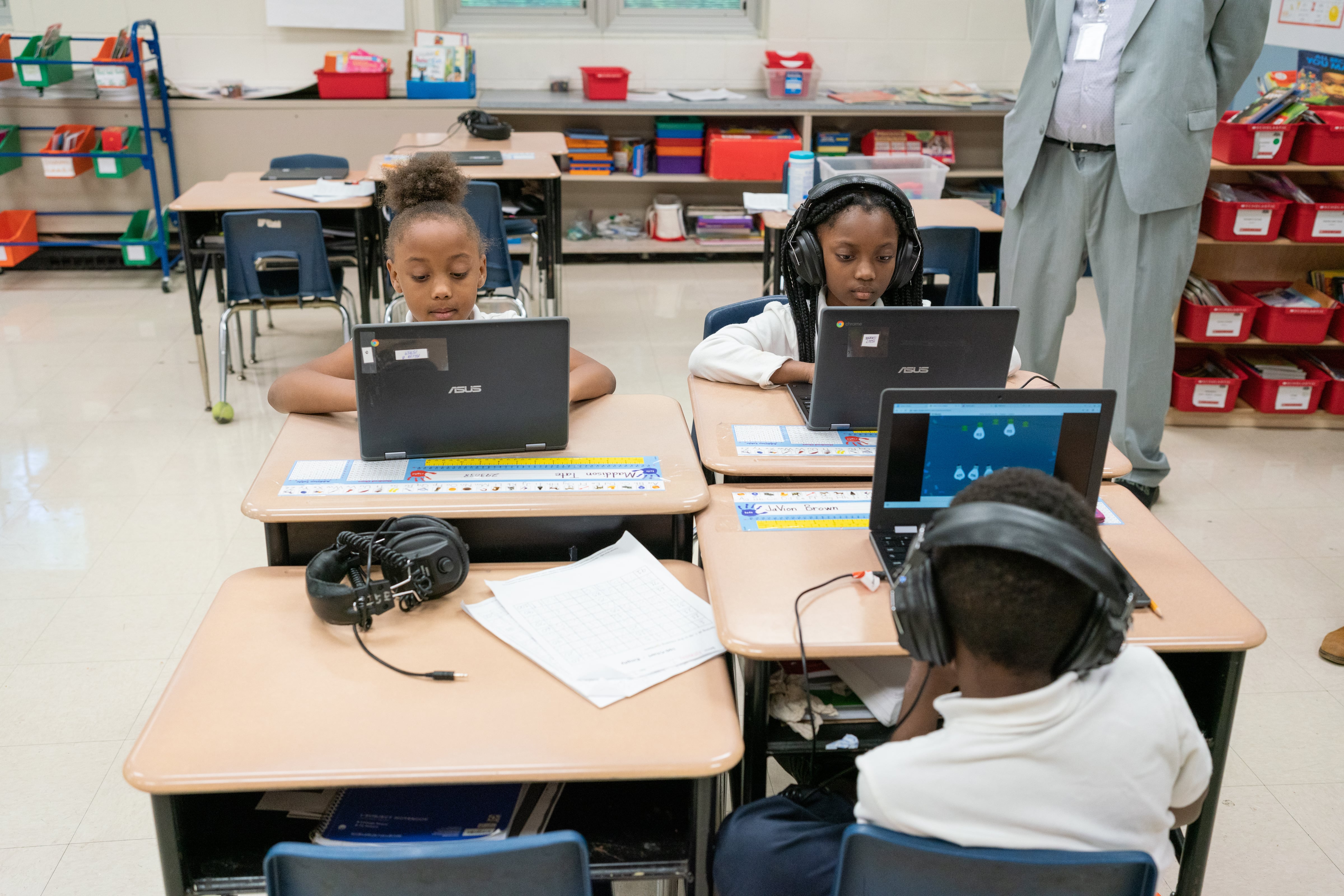

New York City’s fifth and eighth graders will have to take this spring’s state tests — for English, math, and science — on computers, giving schools a nine-month runway to prepare 140,000 students to make the switch from pen and paper.

A substantial amount of work may be ahead to ensure the transition goes smoothly. Of the third to eighth grade students, only 16,300 took computer-based tests last year, according to state data obtained by Chalkbeat. Though a big jump from the year before, when about 1,070 kids took the tests via computer, it’s still a fraction of the number of kids expected to take the tests on computers this school year.

In the 2024-2025 school year, all fourth and sixth graders will be required to take the tests on computers, and by spring 2026, third and seventh graders will join the mix, completing the shift to computer-based testing for all students. (There will be accommodations for students with disabilities who need to use paper, officials said.)

The New York State Education Department last year proposed spending $21 million to support the transition to computer-based testing for grades 3-8 for English and math and science for fifth and eighth graders, but the state’s final budget did not include the funding. Forty-eight states, including New York, have already started using computer assessments.

“It’s time we join the 21st century, and computer-based testing is how we do it,” Zachary Warner, assistant commissioner to the Office of State Assessment, said.

But some New York City teachers don’t think their schools or students are ready for the transition.

Teachers fear that without resources, such as updates to their building infrastructure, computer labs, and computer lab teachers, they won’t have the bandwidth in their academic day to support the needs their students will have as a result of the switch. Teachers also fear that students won’t perform as well on computers.

Officials from New York City’s education department declined to comment on the transition.

Computer-based testing will be more efficient, officials say

Warner said computer-based testing will be more efficient for teachers, allowing teachers to grade exams faster. Schools will also have more flexible and expanded testing schedules, which could avoid previous problems with tests being scheduled during Muslim holidays. (This year, for instance, Eid al-Fitr conflicts with the reading test.)

Eventually, computer-based testing could lead to computer-adaptive testing, which is where a test adapts to the student’s level of work and will produce harder or easier questions based on the student’s performance.

“With computer adaptive testing, we could meet students where they’re at, it would help those that are struggling and challenge those that are performing higher. This could make a real difference for all students,” Warner said.

NY’s computer-based testing has seen some glitches

The state’s move to computerized testing experienced a setback in 2019 with technical glitches that ultimately led to nearly 7,000 students’ exams not being properly completed. (New York City only had a limited number of schools affected at the time.)

The state acknowledged those problems in a 2022 memo, saying that changes have been made. The state is switching to cloud-based servers using Amazon Web Services. More than 230,000 students from over 1,000 schools statewide took computer tests in 2022 with no significant technical concerns while using the new cloud-based servers, officials said.

Studies also have shown that students tend to do worse on exams taken on a computer or a tablet than on one taken with pencil and paper. In one study, students in elementary and middle school performed worse on tests done by computer, though it varied by age and subject. Students from low-income families did worse in all subjects after transitioning to computer-based testing. But more practice with technology can lessen the impact.

Warner said the state will ensure students and teachers receive training as they prepare for the switch. “A kid will never sit down on the day of a test and [have] it be their first time in front of a computer,” he said.

Some NYC teachers fear schools aren’t ready for transition

The city bought 725,000 devices during the pandemic for remote learning, and many of those devices have since been used in classrooms across the city for some local periodic assessments. But some teachers see problems ahead for widespread computer-based testing.

Martina Meijer, a fourth grade teacher in Brooklyn’s District 22, said the experience they’ve had so far with iReady assessments her school administers has been “a complete disaster.” Only 16 of her 26 students have functioning devices, even though some students received devices from the city and the school has 20 computers available to fourth graders at the school.

“It takes about seven to nine school days to get all 26 students through one assessment test,” said Meijer.

Samantha Revells, a third grade teacher at Brooklyn’s New Lots School, said it takes about 45 minutes just to get her 25 students logged into their accounts in order to begin the testing process — that’s with the assistance of a paraprofessional and student helper.

Both Revells and Meijer said students tend to rush through computer-based tests versus paper tests.

“We have to monitor them so closely when they do computer-based exams, because if not they’ll just click and click because they become so impatient,” said Revells.

Meijer said computer testing also doesn’t work as well for some subjects. “Having students complete math problems on a computer versus paper discourages them from doing the annotation that we’ve taught them to do when working out a problem,” she said.

Meijer said her school’s electrical wiring also isn’t equipped to handle computer-based testing.

She said she was told that devices such as a Corsi–Rosenthal Box, a handmade air purifier, and a miniature refrigerator required too much power to use in her classroom. However, she’s expected to charge more than 30 devices.

She spent $100 on surge-protected power cords for her classroom because she feared cheaper cords could cause a fire.

“This switch isn’t helping teachers. It’s inefficient and it’s adding more work for us,” said Meijer.

Correction: This story initially said the state Education Department would allocate $21 million to support the move to computer-based learning. Ultimately, that money was not included in the state’s final budget.

Eliana Perozo is a reporting intern at Chalkbeat New York. You can reach her at eperozo@chalkbeat.org.