Leslie R., a recent Brooklyn high school graduate, still thinks about the February afternoon that three people were shot outside her campus.

She watched police gather at the scene from a window inside the Williamsburg Charter High School. Her brother, a ninth grader with no cellphone, had already left the building. She had no way to ensure he was safe.

“You shouldn’t have to worry about that,” she said. “You shouldn’t have to worry about somebody being shot, or somebody dying.”

Students and educators at the school continue to reel from that day, when violence arrived at their doorstep. A teenager, who didn’t attend the school, allegedly shot two students and a staff member. All three of the shooting victims survived. But the trauma of the incident has lingered among members of the school community.

In the immediate aftermath, reporters flocked to the scene to interview students — carrying cameras and microphones — an ordeal students described as further traumatizing as they tried to make sense of the situation. Though the overwhelming attention has for the most part faded, the community continues to feel its impact. (Some students’ last names are being withheld to protect their privacy.)

The school bolstered security efforts, installing metal detectors and conducting bag checks after the shooting. It brought in additional counseling services. Teachers gave space for discussion in class. And in the months that followed, the community stood unified in pushing for changes that could help prevent other shootings from happening at local schools.

While gun violence at schools remains rare, it often occupies outsized space in the minds of children. Young people in New York City also feel the impact of shootings in their larger community. As of April, roughly 20% of shooting victims in New York City this year were under 18, NYPD data showed. And between 2018 and 2022, the number of teenagers arrested and charged with murder grew at a rate twice as fast as adults, according to the state’s Division of Criminal Justice Services.

As high-profile school shooting incidents have spurred national movements over the past decade — mobilizing students to advocate for change — that trend has continued on a smaller scale locally, as students call for action to help make their neighborhoods safer.

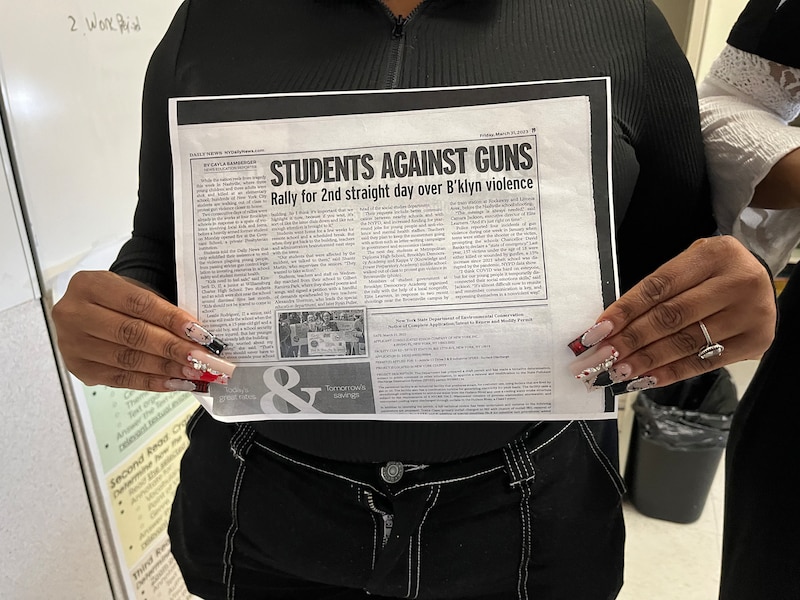

For Williamsburg Charter High School, that meant holding a rally, with students making signs and performing, as they called for local changes they believe could help make their community and others safer. So far, their efforts haven’t resulted in any concrete changes, but that hasn’t stopped further action from teachers and students. The school is planning to hold another rally in the fall, along with encouraging students to write letters to legislators in a continued push for policy changes in New York.

The city has taken some steps to address concerns about youth-related gun violence: holding weekly meetings between school administrators and local police precinct commanders, bringing violence interrupters to schools, and creating opportunities for discussions between students and NYPD officers. This year, though the number of shooting victims in New York City has dropped by nearly a quarter from more than 700 last year, young people still feel the urgency.

“After the shooting, in some students, it awakened a part of us,” Leslie said. “This is the world that we live in. This is reality. So what can we do now to help?”

Students push for change, even as fear lingers

After the shooting, the school transitioned to remote learning for seven days, followed by the week-long mid-winter break and a phased-in return. During that time, teachers Alexandra Sherman and Ryan Fuller felt an urgency to take action.

“Something like this can’t just happen and we go on as usual,” Sherman said. “As a community, we needed to heal emotionally.”

It began with a petition calling for an end to gun violence, along with concrete measures — like expanded partnerships between neighborhood schools and the NYPD and legislation to support school-to-school information networks. The petition also called for improvements to violence interrupter coordination in the community, streamlining communication between schools and the groups who work to de-escalate potentially violent situations. They also called for expanded funding for schools’ social-emotional support and after-school programs, and job opportunities for young people. The petition has since garnered nearly 4,000 signatures.

From there, Shante Martin, an assistant principal at the school, connected with New Yorkers Against Gun Violence to organize the rally in March.

“I feel like the students gave us a push,” she said. “Because they were really like, ‘We need to do something.’ They kept reaching out, they kept emailing us, and telling us that we have to do something so that we can move forward.”

Witnessing violence or tragedies can often spur young people into action, said Sara Suzuki, a researcher at Tufts University’s Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement.

For students who do get engaged, though, it’s critical they find support from their community, she said.

“The link between mental health and political activism can be negative, unless there is a supportive environment for the young person,” she said. “It’s not that if a young person gets engaged post-massive political event, that will automatically help them process that trauma or help them heal. It really needs to be in a supportive civic environment.”

At Williamsburg Charter High School, students encouraged one another to come to the rally, and to speak with social workers and other support staff, Martin said. To Sherman, the experience has brought the school community closer together. But the teacher still feels the aftereffects of the incident. She’s still on edge when hearing sudden loud sounds in her apartment.

The shooting weighs heavily on the students, too.

“That fear is still here,” said Arianna S., a recent graduate of the school. “Sometimes, we’ll be feeling wary about coming to school.”

Students seemed more subdued and anxious in the aftermath of the shooting, said Brittany Gozikowski, a social work counselor at the school. She saw a slight initial drop in attendance, too.

“A location where an incident took place can be triggering,” Gozikowski said in an email. “It can ignite overwhelming emotions that the body is naturally adapted to flee from. So that can look like skipping school, requesting to do learning remote, or finding a new school altogether. However, coming back to that space and finding it safe — finding a supportive community and people who care — that can be healing.”

She worked with some students and their families to “process the trauma,” she said. She helped them “take small steps toward eventually getting back in the building and not being hindered by anxieties.”

Anti-gun violence rallies in Bed-Stuy

At another school in Brooklyn, anti-gun violence rallies are an annual occurrence, featuring student poems and performances at Restoration Plaza in Bed-Stuy.

Middle schoolers at Launch Expeditionary Learning Charter School have been holding walkouts and rallies against gun violence for eight years — an act that has given Tiayana Logan, the school’s director of enrichment, a “renewed sense of hope.”

Students and school staff gathered in the plaza last month, sporting orange T-shirts calling for an end to gun violence.

Neighborhood violence impacts everything from student mental and physical health to academic performance, Logan said, adding students are constantly considering how they can stay safe moving to and from school.

“These are things that 10-year-olds and 12-year-olds are thinking about,” she said. “It’s our job as school officials, as teachers and leaders, to reassure them every day that they will be safe.”

Sonali Rajan, associate professor of health education at Columbia University’s Teachers College, noted the impacts of gun violence on mental health can be devastating.

“It’s not just individuals who are shot and killed with firearms,” she said. “But even for children who survive a school shooting, who witness gunfire, who regularly hear gunshots, who have lost a close friend or family member to firearm violence — these are examples of indirect experiences with gun violence that absolutely shape a child’s sense of stability and safety.”

Both short- and long-term intervention are critical in helping children and teenagers process a traumatic incident, particularly as students may face multiple, compounding incidents over their time in school, Rajan said.

Diamond Smith, an alumni of Launch and recent high school graduate, has been thinking deeply about gun violence and its impact on her community for years. She remembers a time before students at Launch had a plaza to host the rallies — when they gathered just outside the nearby Applebee’s to make their voices heard.

Smith was in sixth grade during the second rally, and since her time in middle school she has worked with Save Our Streets to help keep students safe from gun violence. To her, the anti-gun violence rally helped her understand what was happening in her community around her — a realization she equated to landing in a pool and needing to learn how to swim.

“I want to give kids a safe space,” she said of her work with SOS and as an after-school teacher for younger students. “Because out there isn’t always safe, maybe sometimes home isn’t safe, but you have somewhere to put all your emotions. When you come here, we’re here for you.”

Her time at Launch and with SOS helped crystallize her own goals beyond school. Smith, who will soon attend Albany State University in Georgia, hopes to help those who are struggling — first as a social worker, and eventually, as a lawyer.

“I want to do public service work. I feel like that is my path,” she said. “The gun violence work, the outreach, all of it — it made me realize that.”

‘The activist years’

Students at Williamsburg Charter High School watched in the weeks that followed the incident as more shootings occurred across the country — including one in Nashville that sparked national coverage. Seeing those incidents brought back memories of their own experience, and students said they empathized with the victims on a deeper level.

“It’s one thing to realize and know about it, and it’s another thing to experience it,” said Savannah F., a recent graduate. “It made me more aware of how much not only legislation is not doing enough for us, but also just how exhausted we are.”

It’s been challenging balancing advocacy work with their studies, college applications, and more — but it’s also helped fortify their interests moving forward. Leslie said she plans to work in government in some capacity after college to address systemic issues, including gun violence. For Arianna, this experience has given insight she’ll carry forward as she hopes to study psychology and work in counseling after graduation.

“I never envisioned having such a close connection to this topic,” Arianna said, noting their time in high school has also been disrupted by major incidents like the murder of George Floyd and the pandemic.

“It’s just mind boggling. We already didn’t have the best four years, because of COVID and everything in general. So we tried to make the best of it,” she said. “But I feel like the last four years have been the activist years.”

Julian Shen-Berro is a reporter covering New York City. Contact him at jshen-berro@chalkbeat.org.