Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to keep up with NYC’s public schools.

For Paul Trust, a Queens parent, the first day of summer school came with a surprise.

Last year, his three daughters couldn’t wait to head to Summer Rising, the city’s free summer program, each morning, he said. They enjoyed activities like a slime truck, which came to campus with a hands-on laboratory, and the water slides set up in the school yard.

But shortly after the girls began their program at a new site this year, P.S. 60 in Woodhaven, Trust could tell something had changed.

“By the end of the first day, they were like, ‘I don’t want to go back,’” he said. “It was just outright revolt.”

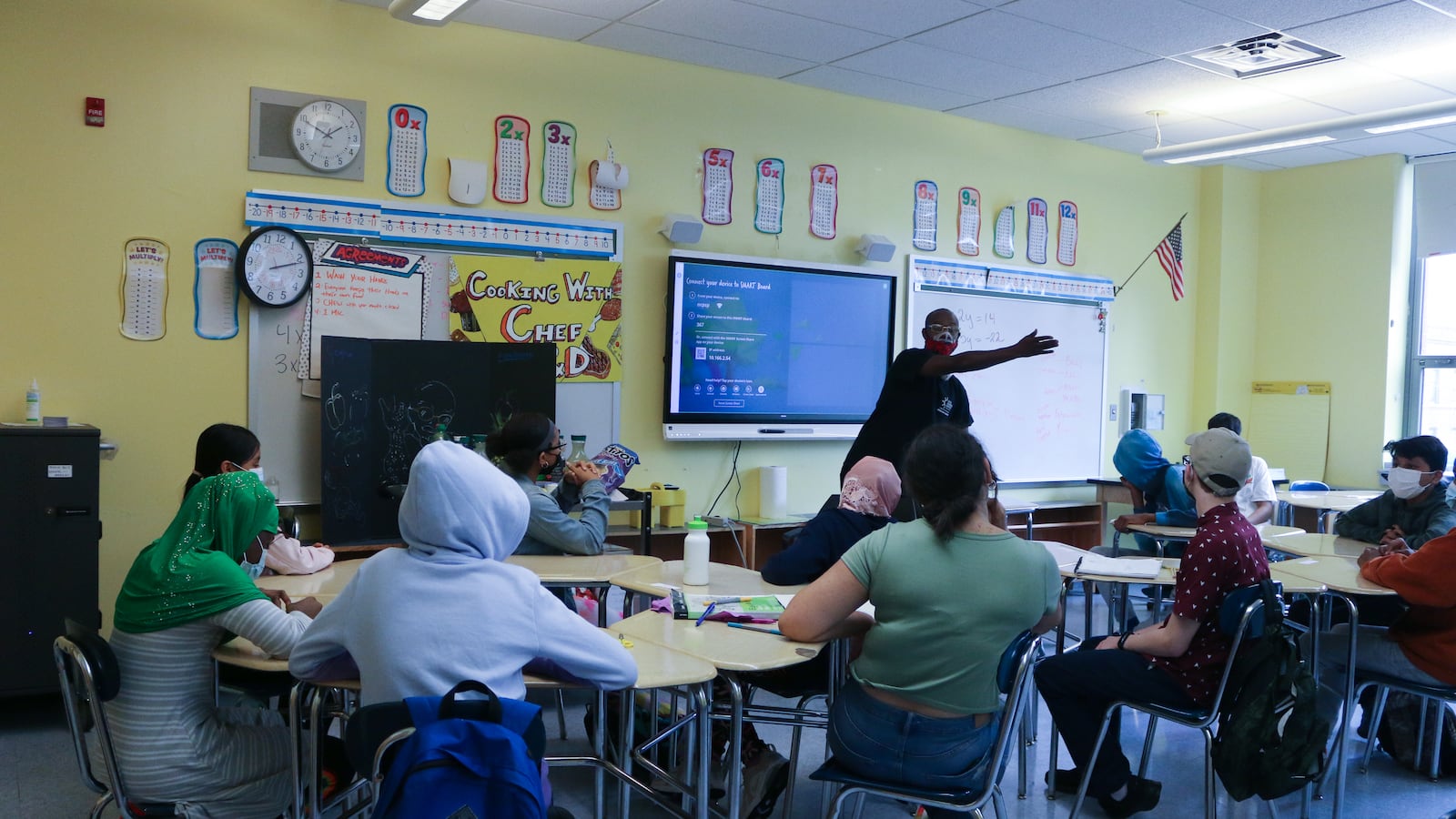

Summer Rising, which runs at hundreds of sites for six to seven weeks in July and August, has been wildly popular, providing students in grades K-8 across the five boroughs with academics in the morning and enrichment activities in the afternoon. It helped reframe what summer school could look like, no longer reserved just for academically struggling kids. This year, the city rejected roughly 45,000 applicants, after the 110,000 available seats were filled. (Some of those applicants eventually got spots as seats freed up, though others were left scrambling for child care.)

Most parents heap praise on the program for helping students learn over the summer months and assisting families with a free child care option. Many are also hopeful that the program will continue next summer even as federal relief money — which funds a big portion of the program — dries up this year.

But while Summer Rising continues to garner praise, some parents at multiple school sites told Chalkbeat they decided to withdraw their kids from the program this year. They cited morning assignments that bled into the activity portion of the day and a lack of activities or field trips — which some site providers said were affected by severe weather. The program’s success had in part relied on its blending of learning and fun, and some worried that balance had shifted for their children.

For Trust’s daughters, their time outdoors was limited to a small fenced yard, he said. Sometimes, they remained indoors all day.

“It seems like they just sucked the fun out of it,” he said.

Despite their complaints, Trust kept them in the program — but he said he was unsure whether he’d enroll them again if the program returned for another year.

It’s been difficult to find buses that can transport students for field trips, said Tanya Walker, a middle school programs director at Cypress Hills Local Development Corporation, a community-based organization that provides enrichment activities at some Summer Rising sites.

The overall program was successful this year, but Walker said that access to buses Monday through Thursday was limited, with few buses available on Fridays. While that issue wasn’t new, trips often fell on Fridays, as did weather-related problems this summer. Most of their sites this year were only able to do between two and three trips altogether.

“Two Fridays were rained out, and one Friday they had a heat wave, so they couldn’t do any outside activities,” she said. “Not being able to provide that experience really does change the momentum and the joy of summer camp.”

Nick Ferreira, senior vice president of youth development at the Child Center of NY, a nonprofit that provided afternoon activities at P.S. 60 and other sites, echoed that heat advisories and air quality concerns affected outdoor activities. He also said that sharing school sites across multiple programs and organizations could have limited outdoor time as well.

Most of their sites have been able to conduct roughly five field trips over the course of the program, he said

Citywide, however, schools this summer have seen more field trips across the board, increasing by about 1,000 trips to roughly 3,000 in total, according to the city’s Education Department.

“As summer comes to a close, we’re thrilled that students across New York City have engaged in critical academic recovery and exciting enrichment activities and field trips this year,” said Jenna Lyle, an education department spokesperson, in an emailed statement.

The city also made available a “full catalog of supplemental materials” to help teachers, Lyle said, highlighting Minecraft Education, coding and computer science, financial literacy, mindfulness, civics projects, and other project-based learning experiences.

Parents continue to report positive experiences

Established by former Mayor Bill de Blasio during the pandemic, Summer Rising has been funded largely through federal relief funds that are set to expire next year, leaving the fate of the program in doubt. At its inception, the program intended to help students transition back to school after remote learning. Mayor Eric Adams, who has voiced support for year-round school, has talked about the importance of the program to prevent what’s known as the “summer slide” when it comes to academics.

“Almost 40% of what children learn throughout the school year is lost during the summer months,” he said at a press conference in July.

“It doesn’t mean that the summer must be boring, but it means that part of the continuation of learning should continue throughout the summer months,” he said. “Those summer months of just doing nothing, just hanging out at the park or just going to the local corners to stand by, that does not happen in affluent communities.”

Education research has shown that students learn less during the summer months, but some researchers remain divided over whether they actually lose ground. Research does show that summer school programs can have a positive impact on kids.

For many families, the program has remained a valuable resource and positive experience.

John Haselbauer, a Brooklyn parent who enrolled his 8- and 11-year-old kids in Summer Rising again this year, praised the convenience of the program.

“It’s been great,” he said. “To be able to send kids and keep them occupied in the summer, rather than having to find some expensive camp, or having them stay home to watch TV or surf the internet.”

His kids have gone on field trips roughly once a week, Haselbauer said, and his oldest child found the academic portion of the day especially engaging and fun.

Leonari Jones said her 8-year-old son has loved his first summer in the program at Conselyea Preparatory School.

“By the time I pick up my son, he’s nice and tired,” she said.

Some parents withdraw from program

But despite positive experiences elsewhere, a Brooklyn parent at P.S. 139 said their children repeatedly spent all day indoors, complaining that the only programming involved watching television and playing in the gym.

Their one planned field trip — a visit to the Brooklyn Museum — was canceled on the day-of due to concerns over rain, the parent said.

The parent ultimately decided to withdraw their kids from the program, adding, “I didn’t want them to be miserable for the rest of the summer.”

Tajh Sutton, a Brooklyn parent leader, said she enrolled her 10-year-old daughter in Summer Rising for the first time this year. Initially excited, her daughter quickly soured on the program, as her days often began with individual worksheets and assignments that she didn’t find engaging.

Sutton said she understood the need for additional academic support in the summer months, but wished her daughter’s experience had involved more project-based learning and exploratory field trips or activities.

“I had transparent conversations with my daughter about why they had added so much academics in the summer, but it didn’t change the fact that she just wasn’t having a good time,” she said. “I know I can’t speak for everyone, but my daughter and her peers certainly didn’t respond well to it.”

Since she works remotely and had flexibility, she decided to withdraw her daughter from Summer Rising. She was happy to give it up for a family that needed the spot, she said, though she hoped the program could incorporate more fun into learning as well as bolster other supports for students, like mental health care and resources for vulnerable students.

“It’s not enough to just have somewhere for kids to go,” she said. “Yes, that’s important. It’s a dire need, and without it, the circumstances for families worsen that much more.”

She added: “But just because a child has somewhere to go, that’s not the whole story.”

Julian Shen-Berro is a reporter covering New York City. Contact him at jshen-berro@chalkbeat.org.