The case manager’s office at Harlem’s Mid-Manhattan Adult Learning Center was crowded, primarily with Senegalese men in their late 20s and 30s.

Fatou Kane, the school’s community coordinator, picked up the student sign-in sheet that February afternoon, and with the aid of Patrick Duff, the case manager, started triaging the students’ problems.

Some of the men had received a blue New York benefits card in the mail and had questions about it. They thought it was an immigration document. Another student wanted a school identification card. Others were there to register.

The men were among the 101,200 asylum seekers who have arrived in New York City since spring of 2022. They found their way to the adult learning center, mostly by word-of-mouth and community outreach by the school. But the center is straining to help them: They’re funded by headcount, not the vast and complicated needs of the newly arrived asylum seeking-students. The school is scrambling to provide them with clothing, child care, health insurance, and meals, while also helping them navigate the complicated immigration and legal system.

The center’s principal, Gloria Williams, has been pleading for more assistance. At a Harlem town hall on asylum seekers last year, she described how her school has seen a dramatic increase in recently arrived migrants. She described their desperation, and how students would fight over applesauce thrown out by the day care program the school hosted for students’ children.

“If you are feeding a 3-year-old, it’s what we will call ‘mooshie’ food, you know, stews and applesauce and all of that,” Williams said. “But my students, they eat it because they’re hungry, and they’re not in secure food situations.”

The Mid-Manhattan Adult Learning Center, which is part of the Education Department’s Alternative School District 79, provides free classes for students 21 years and older who don’t have a high school diploma.

There are eight adult learning centers across the five boroughs with numerous satellite sites. The school is one of two adult education centers in Manhattan and offers programs, such as English language classes, GED prep, and numerous technical certification courses. Mid Manhattan’s zone is 119th Street and above.

This year, Mid-Manhattan Adult Learning Center saw a 40% increase in student enrollment, jumping to nearly 3,700 students compared to about 2,600 the year before. The biggest registration jump was for English as a second language courses, according to enrollment data.

The school staff members have learned to be multilingual and multifaceted in their knowledge of NYC social services, becoming the bridge for thousands of new asylum seekers.

According to school officials, about a decade ago, 75% of the students were enrolled in the GED program and 25% were learning English as a new language. Since 2020, that demographic has flipped. Now three-quarters are in the program learning English as a new language. Students arrive at the school speaking only Wolof, French, Portuguese or their ethnic language.

Just as K-12 schools are seeing a surge of needs in schools serving asylum-seeking families, so are the city’s adult learning centers. But unlike K-12 schools, these centers aren’t getting additional support for their needier students.

Adult learning centers like Mid-Manhattan are funded through the New York Employment Preparation Education program. The program retroactively reimburses school systems for services provided based on the number of hours staff spend with a student, but some school officials believe it underestimates the needs of the students.

The city’s Open Arms Project last school year sent an additional $26.7 million to K-12 public schools enrolling asylum-seeking students, according to a May report from the New York City Independent Budget Office. The report did not include schools in special districts like Mid-Manhattan Center’s. Education Department officials did not respond to repeated requests for comment about this.

The center’s employees also wish the city would extend some of the benefits that K-12 students receive, such as free lunch. Employees saw how much it helped this summer when the Education Department provided meals for students for six weeks, Duff said.

“It just never occurred to anyone here that there was that need,” Duff said.

The Education Department said free meals in the city’s K-12 public schools are paid for through federal funds for low-income children, and adult programs aren’t included. Department officials didn’t respond to questions about the summer meals.

To help, the school began giving students food two years ago. The students would come to class hungry, some had not eaten sometimes for days, but they were ashamed to admit their situation — especially the men, Duff said.

The initiative to feed students was started by the school’s principal, Duff said.

In the beginning, Williams paid for the food and toiletries with her own money, according to the center’s staff. Now the school partners with food pantries in Brooklyn and Manhattan. To ensure there is food every week for the students, the pantries alternate on a two-week schedule.

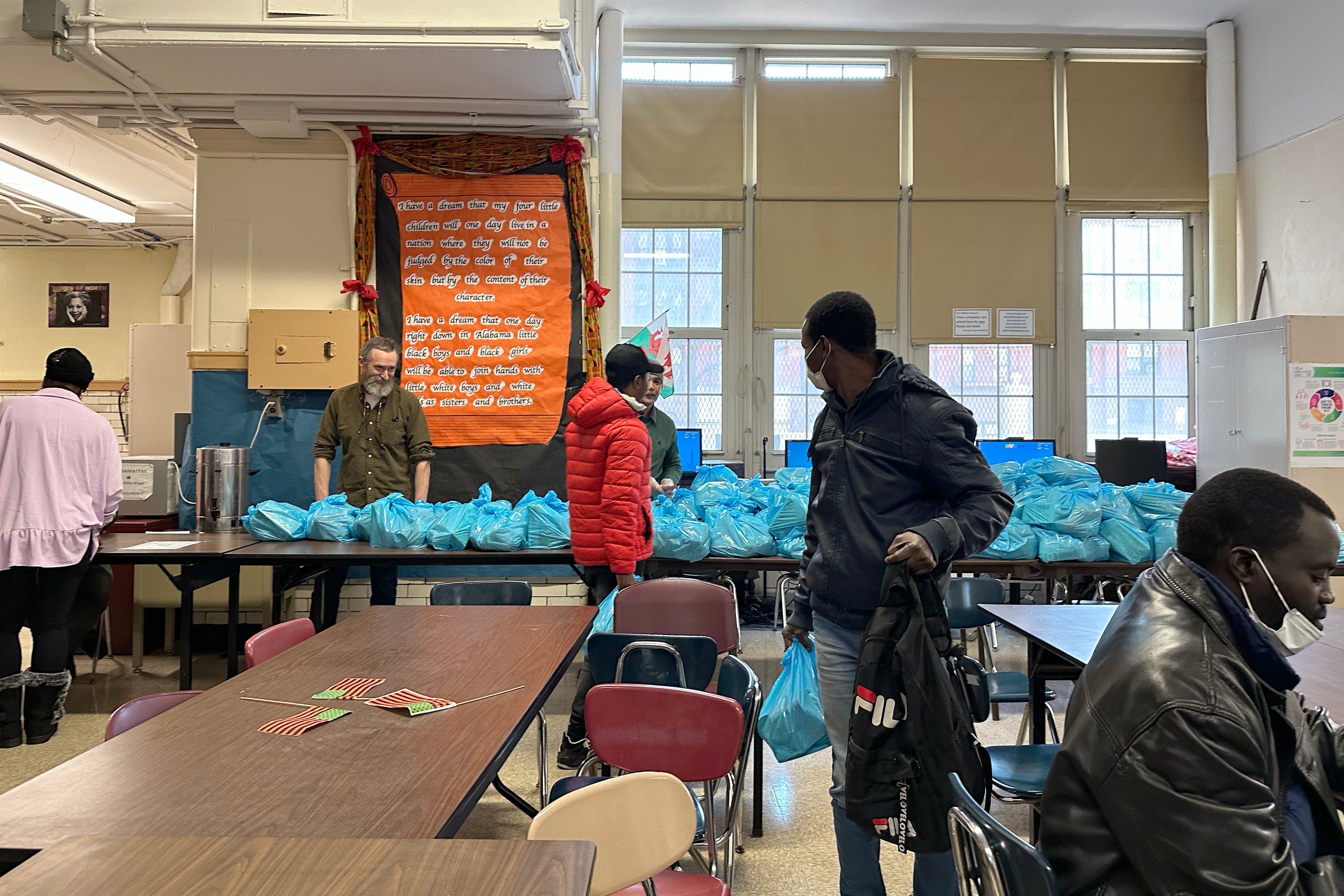

On Tuesdays, the school’s cafeteria is lined with blue bags. Inside is a small bag of rice, potatoes, fruits, juice, and some canned vegetables.

The school hands out an average 150 prepared bags of food each week. They set aside a few bags to be taken to their satellite locations. The school purchased about 100 two-way MetroCards to give to students when they send them to pantries for food.

Center sees needs in African migrant community

Roughly 43% of the school’s students identify as Black or African American, according to demographic data. The school continues to see an increase of African migrants.

There are five case managers, including Duff, and one other community coordinator in addition to Kane.

Kane, 40, is the go-to staffer for African students. She speaks English, French, and Wolof. She is often called upon by other case managers to be a translator.

Kane migrated from Senegal to the United States in 2018 with her two kids while pregnant with her third child. Her husband had been living in the U.S. and had become a citizen. She signed up for the Certified Nursing Assistant Program at the Mid-Manhattan Adult Learning Center and never left.

Williams, the school principal, noticed how Kane assisted other students and hired her as a community coordinator.

“I like to help them. Because I know they need help. It is difficult for them, because they don’t speak English,’’ Kane said about the students.

For Kane, each interaction feels like an urgent call for help.

“When you welcome them, and you say things like ‘Bonjour’ or ‘As-salamu alaykum’ they are so happy,” she said. “Their first reaction is, ‘Do you speak French? You speak Wolof? Oh my God, thank God.’”

Former students seek her out too. Daniel, 35, had been a student at the school, but stopped attending classes to focus on work. He immigrated from Senegal after winning a green card lottery. He had worked in IT security services at the airport in Dakar before coming to the U.S. In New York, he has a job as a CVS store associate restocking shelves and assisting customers, and he lamented his new station in the U.S.

“When you come here, it is like you never went to school. People treat you like you are not educated,” he said. (Daniel did not want his full name used for fear it might impact his immigration status.)

He came to the school to inquire how best to translate his master’s degree from Senegal to the American equivalent. Kane explained the process, but she cautioned him too.

“If you are patient, step-by-step you can reach your goal, first you learn English,” she said.

She understands the joy and easiness the students experience from interacting with her without the language barrier. That is why she emphasizes to students the importance of learning English above all else.

“First go to school and learn English, second follow the rules,” Kane told Daniel.

Students also get help with immigration hearings

Asylum-seeking students often arrive at the adult learning center with no form of identification. The only documents they carry are a collection of forms given to them by the U.S Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, such as immigration court-ordered appearance dates.

The school staff uses these documents to register the students for classes and create their first official photo form of identification: a school ID.

They also help the students complete applications for the city’s free IDNYC, a local government-issued card for residents that can be used to access numerous city services regardless of immigration status.

One of those students was 42-year-old Ousmane. Ousmane fled Senegal after it was uncovered that he was gay. Homosexuality is illegal in Senegal, punishable up to five years of imprisonment. (Ousmane did not want his full name included because of fear it might impact his immigration case.)

“Je suis venu ici vivre mieux en paix. Je me sentais bien ici” Ousmane said in French.

I came here to live better in peace. I feel good here.

Ousmane’s first immigration court appointment was in February, and he did not have a lawyer, nor did he speak English. The school doesn’t directly provide legal services, but they scrambled to help him anyway.

Duff explained to Ousmane that at his first hearing, the goal is to tell the judge he needs an extension to get a lawyer.

Duff created two cue cards for Ousmane. The first, written with a sharpie in capital letters said “I SPEAK ONLY FRENCH/WOLOF” and on the second, “I need more time to process my application. This is my first time here.”

District 79 partnered with Sanctuary for Families, a New York City-based nonprofit, to provide free immigration legal consultation. The adult learning center coordinates with an immigration advocacy manager in helping students find legal immigration services.

Kane and Duff have seen migrants, many of them Africans, give all of their earnings to lawyers who promise to get them working permits and asylum status, but then don’t follow through. Other asylum-seeking students come to see case managers for help because their employer takes advantage of their immigration status by not paying them.

As a case manager, Duff said no day is ever the same and you don’t know what to expect.

“It’s like we’re all putting out fires. We started helping people with issues like this, even if we’re not trained to, you just gotta jump in and help,” he said.

Churchill Ndonwie is a freelance immigration reporter based in New York City. He reported this as a student at Columbia’s Graduate School of Journalism.