Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to keep up with NYC’s public schools.

I first met Miss Anne Marie when she peeked her head through our hospital room door.

“Mom. Is now a good time?” she whispered, tilting her head and looking at me over her glasses.

Her friendly grey-blue eyes met mine, which were bleary, puffy, and strained. She wasn’t wearing scrubs or a lab coat, but a tidy blouse and a neutral skirt. Her salt-and-pepper hair was slicked back in a high, neat bun. Under her arm was a stack of folders, workbooks, and papers.

When she spoke again, her thick Bronx accent carried the city’s education department on its wings. “Hiiii, Mom. Is your daughta ready for school today? I’m her teacha.”

School had been nearly the last thing on my mind.

I was aware it was now September, not by the shift in the humidity or a peep of orange on a leaf. I knew it was by the onslaught of social media posts. My grad school cohort was beginning their first year as teachers. My friends posted photos of their children with new hairstyles and fresh backpacks holding “First Day of …” signs.

For me, each one was a sharp kick. It would have been my daughter’s first day of first grade had her stomach bug that wouldn’t go away actually been a stomach bug. Instead, she was undergoing her first round of high-dose, inpatient chemotherapy.

Not a stomach bug. Lymphoma.

A few weeks before my daughter’s stomach bug that wasn’t a stomach bug began, I graduated with my master’s degree in Educational Theater. When I began my coursework, I had one 2-year-old. By the time I finished, that 2-year-old was 6 and I had another 2-year-old. I was eager to move into my own classroom, to become a bridge connecting students to stories and to one another.

“Mom!? Is now a good time?” Miss Anne Marie tried again. “Can you come into the hallway for a second? I’d like to speak with you about school for your daughta.” I had already turned away the volunteer knitting teacher and a couple of clowns that day. I was ready to shut the door again, to say no thanks. No more kid-cancer world.

But Miss Anne Marie was a teacher, and ever the good student, I followed her instructions. She asked me what grade my daughter was in. Not what grade she would have been if the stomach bug had been a stomach bug, but what grade she was in today.

“First grade! OH KAY! I have another first grader on this floor!”, she said as she peeked in the room and caught my daughter’s eye. “And the other first grader loooooved this story.” That interested my daughter, who peeled her head from “Puppy Dog Pals” on TV and toward Miss Anne Marie.

Miss Anne Marie understood that learning is essential to a child’s humanity.

The educator in me recognized a strong “hook” when I saw one. “Oh, she got her,” I thought. In came Miss Anne Marie with coloring pages and photocopied handouts and a million stickers. My daughter’s first day of first grade was about 10 minutes long.

Before she left and my daughter fell asleep, Miss Anne Marie turned to me and said “Mom, I know you’re new here. Here’s how this works. When she’s admitted, I’ll come to her room to see your daughta, but when she’s outpatient I’ll see her at my table. OK, bye.”

After spending the first 38 days of my daughter’s treatment inside the hospital, she was stable enough to go home for a week. We returned for blood work a few days later and got to see what Miss Anne Marie meant by “my table.” There it was, a small oval table in the corner of the waiting area next to a giant fish tank that had been a patient’s Make-A-Wish wish.

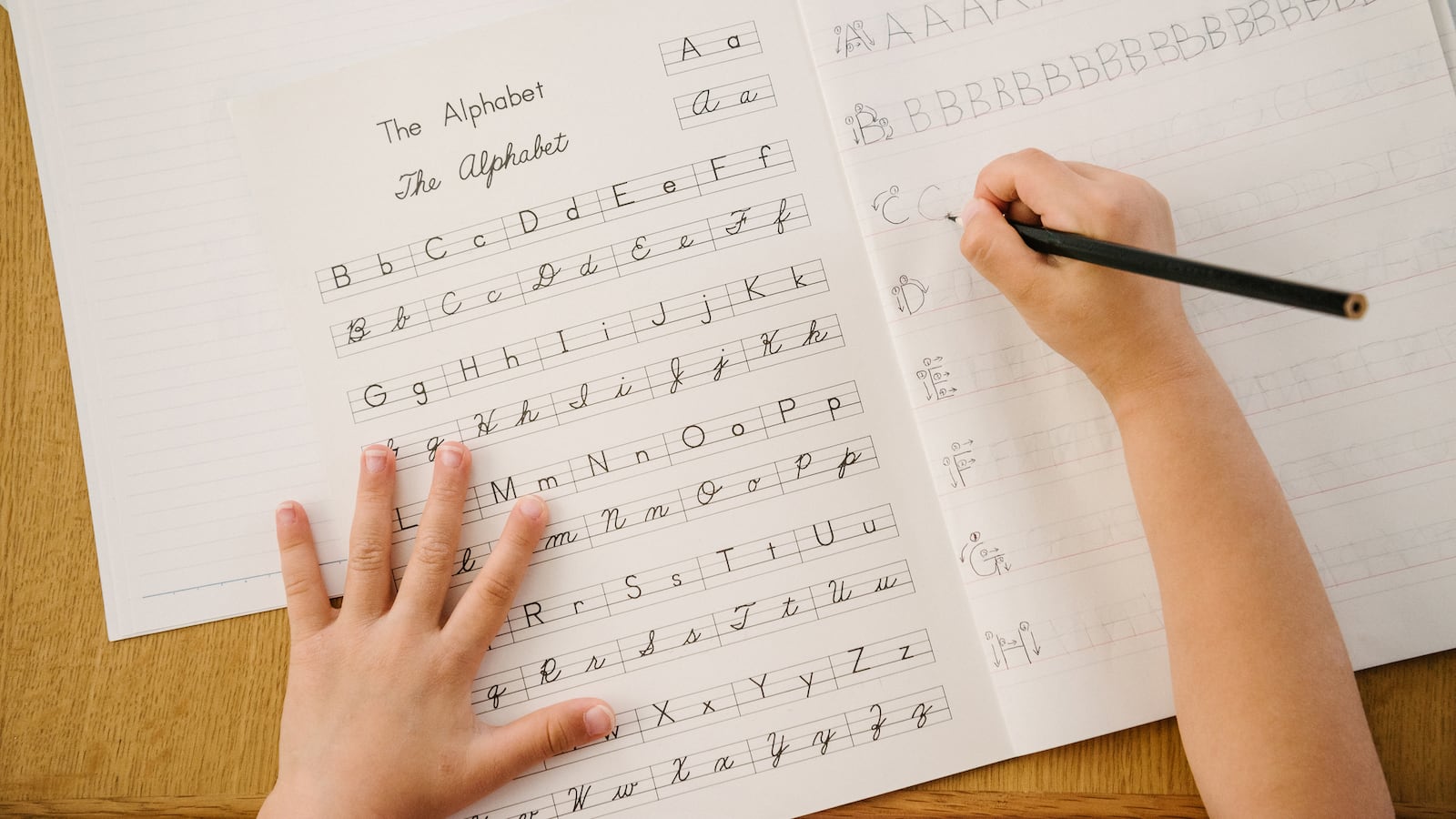

Every morning, Miss Anne Marie unlocked a closet that held her materials and she began taping visual supports, a word bank, and student artwork to the wall to create a makeshift classroom. We saw children, writing their names, coloring in days on a class calendar with their little bald heads, fresh scars, and IV poles full of chemo. They were in school. They were learning. My daughter pulled up a chair.

For 20 years, Miss Anne Marie Cicciu was part of the Hospital Schools Program under District 75 in the city’s Department of Education. D75, as it’s known, offers the highest level of support for public school students with a range of significant learning challenges. Today, the program serves about 300 students a month at city hospital sites and virtually.

“Learning is a Part of Healing,” the Hospital Schools website says. The program provides students with the kind of coursework they would be receiving if they were at school and helps them transition back to the classroom or at-home learning after their hospital stay.

On a typical school day, Miss Anne Marie would welcome children who had come to the hospital for chemotherapy, radiation, scans, or follow-up visits. Every single one of her students needed accommodations, and she rarely saw the same children every day. Each child was welcomed to “school” with Miss Anne Marie’s big smile and Bronx accent. There is room at the table for them and a comforting routine.

When a child has a life-threatening illness, like mine did, it is understandably easy to let academic skills slide. The health and survival of the child become the top priority. Some might think, why bother to educate medically fragile children? Why not just let them have fun? Perhaps they wonder what’s the point if a student learns how to add when they may not see their next birthday.

But Miss Anne Marie understood that learning is essential to a child’s humanity. They hunger for novelty and to understand the world around them. None of these students felt well and yet school was there for them when they were ready. The Hospital Schools Program gave my daughter some agency in her young life.

While some educators might disconnect from their students with life-threatening illnesses for fear of losing them, Miss Anne Marie moved closer. She extended herself to her students and their families. She was a guide on their path of discovering the marvelous simple truth that when you put letters in a certain order, you create words. Now they were readers and writers, not just sick children.

Sometimes Ms. Anne Marie and I would get to talking. I was desperate for small talk, beyond prognosis and protocols. I told her I was a teacher, or at least I was about to be a teacher before all of “this.” She told me about her three-bedroom rent-stabilized apartment on Park Avenue South, where she lived for 40 years until the building went co-op and she was forced out. “My dinner table was here,” she gestured, “And out the window here was the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building. They were my friends. I had dinner with them, in my dining room. Yes, I had a dining room.”

After she moved out, her apartment was cut up into three separate million-dollar listings. She was heartbroken to move across the river to New Jersey, having grown up on Arthur Avenue in the Bronx and lived in Manhattan all of her adult life. She told me she used to take the bus from her new building into her old neighborhood to grocery shop because she didn’t drive.

We weren’t the only ones missing home.

Her move to New Jersey was hard for her in other ways. She was confronted by the boxes and boxes of her students’ work she had saved over the years, including work by her students “that didn’t make it.” She told me, “I know they drew that Letter of the Day, and I know I’m the only person who knows it. And I know they aren’t here anymore, but I can’t throw it away! How could I? My students do beeeautiful work, and I can never throw it away.”

My daughter is now six years cancer-free, twice the age she was when she was diagnosed. Miss Anne Marie has retired, but she still has the boxes of her students’ work.

Jessica Phillips Lorenz is a writer, educator, and cancer-mom. Her work has appeared in Romper, Insider, Parents, Real Simple, MUTHA Magazine, and a theatre festival for babies in Northern Ireland. She is a member of the American Childhood Cancer Organization, Momcology, Piper Theatre, and Emerging Artists Theatre. She lives in New York City with her husband and two children. She’s on Instagram @PlaypracticeNYC.