I will never be independent. That’s OK. No one is.

Don’t get me wrong: I understand wanting to be able to care for oneself. From an evolutionary standpoint, it improves your chance of survival. But when we move the goalpost from surviving to thriving, working together and caring for one another becomes more valuable. I admit I have a different perspective about all of this since I am severely disabled and medically fragile, but I know a few things about succeeding amid adversity.

I’m a junior at Columbia University, and I start each day being lifted out of bed by one of my parents or aides. The bed is raised on legs my dad built and has rails covered with custom padding sewn by my mom’s friend Erin, who also makes costumes for the Muppets. My mom, an engineer, helped Erin with the renovations on her house. We all need help with something.

I cannot feed myself or prepare and administer my medication. Being tube-fed requires bags, tubes, gauze, tape, and a special high-nutrient, high-calorie formula. My medication is prescribed by various doctors, all of whom have billing assistants, schedulers, nurse practitioners, and fellows working with them. The food, medication, and supplies are inventions of scientists and biomedical engineers. They are produced in factories around the world, packaged, shipped, and ultimately delivered to my house by Ralph, the best UPS man ever. My mom always offers Ralph a cold drink on a hot day.

I rely on all these people for breakfast and seizure prevention. They rely on other people to get through their days, too. They may have coffee from a Starbucks or a bowl of Cheerios they pour from the box, but they probably didn’t grow the coffee beans or harvest the oats. Their breakfast depends on factories and trucking, just like mine.

Once I’m dressed, brushed, and washed, I leave for school with Mahmood. He is my aide and my friend. We have been together for 13 years, and he knows everything about me. It is a short walk to the car, and I settle into the back seat, where my dad has installed a race car five-point harness to keep me safe and comfortable for the drive from my parents’ house in Queens to Manhattan. During the ride, we catch up on fantasy football and plans for the week.

There is always a parking spot waiting for us near Columbia since I have a parking pass for people with disabilities. Such accommodations are made possible by New York taxpayers and voters. It would not be possible for Mahmood to spend his days with me unpaid. He has living expenses and three adorable nephews who need baseball gear, books, and art supplies. Luckily, his salary and benefits are paid for mostly by a state-supported program called Self-Direction, which assists people with severe disabilities who are living, learning, and working in the community.

No one plans on needing help caring for themselves, but many people will need help with daily tasks at some point in their lives. About 11% of all New York City residents have disabilities, including 47% of city residents over age 65.

Monday at 2 p.m., I attend an art history lecture, followed by a small discussion group. I roll in and take the open space in between the fixed seats. The professor uses a microphone and his lecture appears at the bottom of the projection screen when he speaks.

While I pay close attention to the images on the screen and his terrific explanations, I cannot take notes fast enough to keep up. I don’t worry though, since one of my classmates is paid to share their notes with students who cannot take their own. I communicate by standing and hitting a six-switch array with my chest, which drives computer software my dad wrote for me. (Here’s a video of me typing.)

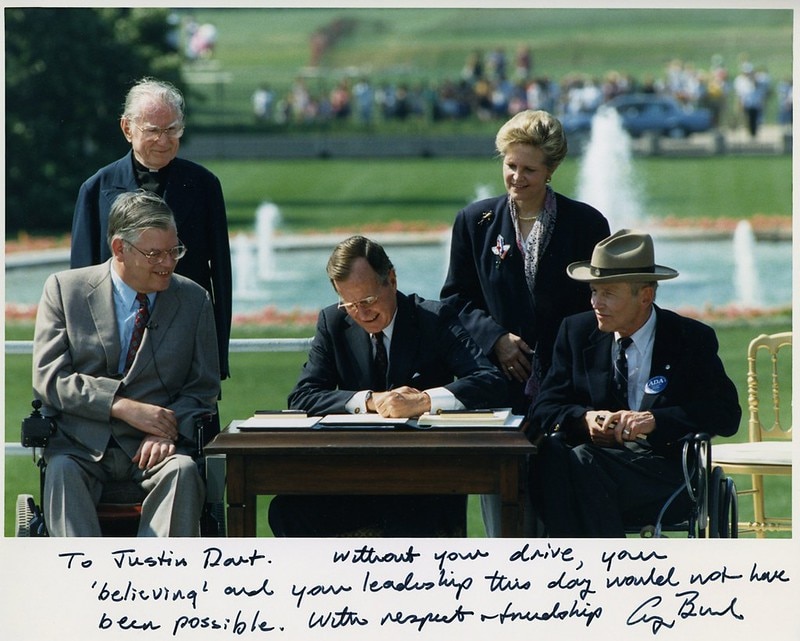

The laws and the regulations that have made my life and schooling possible have been hard-won. In 1977, disability activists staged the national 504 Sit-In to demand their civil rights, and in 1990, activists with disabilities left their mobility aids behind and crawled up the steps of Congress in what is known as the Capitol Crawl. Such activism helped lead to the passage of the Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990, federal legislation that mandates public spaces be made accessible to people with mobility challenges and those with other disabilities.

These accommodations are necessary to ensure that I have access to an education and opportunities afforded to my peers without disabilities. It does not mean I’m entitled to the same destiny, only that I’m offered reasonable assistance, like more time to complete an exam, or opportunities to participate in class even though I am non-speaking.

Making rules is important, but having people who follow them makes my experience at Columbia possible. Laura Dayan in the university’s Disability Services office regularly communicates with my professors, sends my switches to my classrooms, and schedules testing around my physical limitations and medical needs. Laura is the face I know, but the campus is filled with others who advocate for accessibility projects, maintain elevators, and send me their lecture notes. I rely on and appreciate all of them.

At Columbia, I contribute to our community by listening to others and sharing my perspective. I always start with listening. Part of that is by necessity since I need to stand to access my communication system. Even when I could speak first, I choose to listen because people need to know that their experience is acknowledged and appreciated. When we listen, we are prioritizing other perspectives over our own.

Despite my challenges, I have a life of fortune. From the moment I was born, I’ve been adored, supported, pushed, and expected to do great things. My parents’ belief in me, and the persistence and confidence they instilled, empower me to tackle every day. I model that behavior, reminding those around me that they are not alone. I see their challenges, and I have confidence in them.

The visible and audible nature of my disabilities means they cannot be hidden. But human vulnerabilities, whether invisible or in plain view, are not shameful.

After class, my body is tired but there is lots of reading and research to do. I return to my dorm room, where I stay over from Monday through Thursday, and another aide, Ben, arrives so Mahmood can go home to his family. Ben bathes me, and we settle in for an evening of selections from books and journals. I can read but my involuntary movements make it impossible to keep track of my place on the page. Some documents are formatted for text-to-speech, and others Ben reads to me. He is good at reading aloud since he studied acting in college, and he gives the best baths. We share a love of film, especially horror movies.

Needing a team may seem like a sign that I am completely dependent on others. After all, I am never left without someone who could get me out of the building in case of a fire. The truth is everyone needs a team to help them through life. Weathering difficulties and celebrating accomplishments are best done in community.

I am not independent and, with the possible exception of hermits and desert island survivors, neither is anyone else. We all need friends, and we all rely on strangers who fabricate and maintain the world around us. We are all vulnerable to disability and will likely experience it at some point in our lives. And we all need examples to remind us that persistence and patience can produce great things.

Abey Weitzman is a junior at Columbia University. He enjoys traveling and staying home. Weitzman is a graduate of Bard High School Early College Queens. As a disability advocate, he hopes to use his writing to create change for his community. In 2017, Weitzman wrote in Chalkbeat about navigating New York City public high school admissions as a wheelchair user.