Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to keep up with NYC’s public schools.

Walking through the halls of Lafayette Academy, an Upper West Side middle school, Principal Brian Zager greeted each student by name.

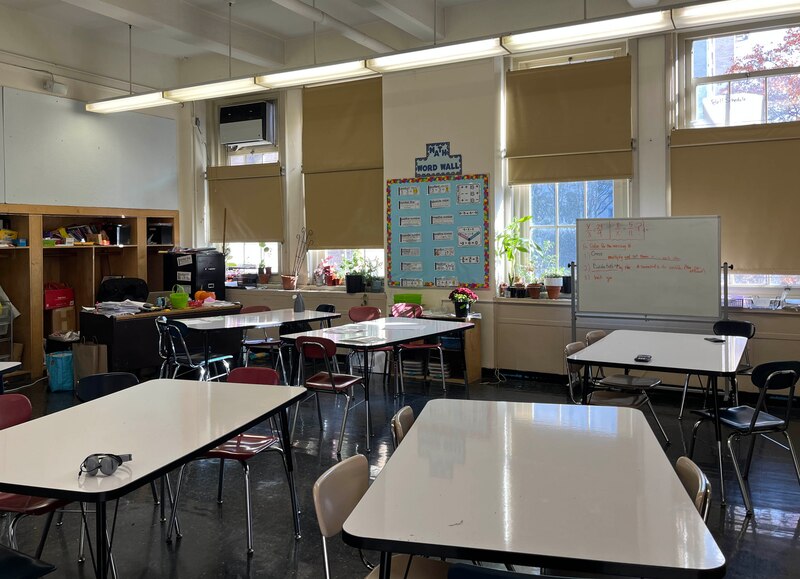

The building on West 93rd Street was especially quiet that November morning, with seventh graders out on a field trip to Central Park.

In classrooms, eighth graders worked on finishing their high school applications. On the third floor — a space shared with the Manhattan School for Children — students in the dual language program practiced their French.

Lafayette Academy, where Zager has served as principal for the past decade, has prided itself on its small school community, allowing students and staff to develop close bonds. This year, the school saw its student body grow by roughly a quarter to about 200 students as Lafayette merged with West Side Collaborative, a small progressive middle school serving higher shares of students of color and students from low-income backgrounds. The move spurred ample protest from both school communities last year, even as officials said it could shield them from the negative effects of shrinking enrollment.

But in the halls of the newly merged school, that tension was no longer palpable. Each class has a mix of students from the two former communities, Zager said.

Leadership at the school has remained optimistic about the outcome of the merger, praising the benefits of bringing staff and students from disparate communities together. But some families expressed concerns over whether the city’s Education Department provided adequate funding to support the larger and more diverse student population, while others continue to protest the decision to merge the schools at all. Some West Side Collaborative families remained unhappy that Lafayette kept its building, principal, and name.

Morana Mesic, a parent and former PTA president of West Side Collaborative, transferred her son to another school after the merger was approved — calling it a closure.

“We’re at a point where we wish that we never stepped into West Side Collaborative,” Mesic said. “Because it hurts that much more to be back in the same old public school system.”

Trying to stave off enrollment losses before a merger is needed

As the city continues to grapple with steep enrollment losses suffered during the pandemic, officials have warned more school mergers may loom ahead. At least half a dozen more proposed school mergers will be considered by the city’s Panel for Educational Policy over the next two months, according to its website.

“It’s hard to figure out how people can run a full comprehensive high school with 80 kids as your entire school,” schools Chancellor David Banks told Chalkbeat in November. “And we have schools with those numbers.”

West Side Collaborative had just 75 students last year, less than half of Lafayette’s roster. About 46 of its students moved into Lafayette’s building this year along with eight staffers, making up about a third of the newly merged school’s employees. (Others from West Side Collaborative’s 20-person staff were transferred to other schools or retired, according to the city’s Education Department.)

Despite its dwindling size, West Side Collaborative fostered a passionate community over its years in operation. Amy Stuart Wells, dean of the Bank Street Graduate School of Education, said there was a disconnect between outside perceptions of the school and the quality of education it provided.

Despite the enrollment losses the school was facing, it had strong support for students and a robust project-based, student-centered approach to learning, said Wells, who studied West Side Collaborative as part of a project on diverse public schools. Wells worked with the school to help shift the narrative by developing promotional materials like brochures, but she said it can be challenging to combat outside perceptions.

“In the school choice processes, sometimes schools get labeled as ‘good’ or ‘bad,’ particularly in the parent networks,” she said. “It’s hard to change that narrative and that framing, even if there’s some really, really good work going on within those schools.”

With time, the losses became especially steep. In the five years preceding the merger, West Side Collaborative had seen a 58% decline in enrollment.

Still, community members sought another solution. In the months leading up to the merger, parents and staff at West Side Collaborative fought against the proposal, arguing that its approval would in effect see their institution closed.

The school served overwhelmingly Black and Latino students, with more than 80% of students living in poverty, according to city data. Some community members felt uneasy about merging with Lafayette Academy, a school with a higher share of white students and fewer students from low-income backgrounds.

In some ways, the merger served a goal that has proved elusive in one of the nation’s most segregated school systems. It provided a path toward further integration in District 3, which encompasses both schools. The district is one of a handful in the city that has remained focused on integration. Last year, the school district won a federal grant to help foster diverse schools.

Meanwhile, some parents at Lafayette expressed concerns over the lack of concrete details on how staffing and other decisions would shake out.

Despite the pushback from families at the time, Superintendent Kamar Samuels said he viewed the schools as a good fit to merge because they shared “a student-centered approach” to instruction.

“Both schools had staff that cared deeply about the progress of all students, but in particular, the most marginalized students in the school,” he said.

Finding a balance when schools join together

The Upper West Side merger isn’t the first time two demographically distinct schools were joined together. In 2020, for example, the city approved a proposal to move the Academy of Arts & Letters, a disproportionately white school in Fort Greene, into P.S. 305, a majority-Black school in Bedford-Stuyvesant.

Pilar Ramos, principal of the merged school, said it took time for the two communities to come together as one, particularly as the onset of the pandemic turned classes virtual. To avoid privileging one school over the other, the communities worked together to come up with a new name, referring to themselves as “Arts & Letters 305 United,” Ramos said.

“When people feel like they’re going to be included — that we’re together for something that’s going to be greater than what it was on its own, I think that’s an important part of a merger,” she said. “We’re not going to be just one school or the other, or just as good as one school or the other. We’re going to be better than both of them.”

At Lafayette, Zager said his work began even before the merger was approved. He met with parents and students from West Side Collaborative before the vote and in the months leading up to the school year, trying to alleviate any concerns or anxieties they might have about the move.

Families from both schools were afraid of losing their school identities, he said. But months into the school year, Zager noted the students haven’t had trouble acclimating. A few former West Side Collaborative students were even elected to student council, he said.

“When it comes down to the kids, there’s this innocence that just finds its own way to fly,” he said.

To Shawn West, a dean at Lafayette, the small school environment has allowed the merged community to develop bonds quickly.

“We feel like we’ve known these kids for two years,” he said.

Staff came together ahead of the school year to build team cohesion, swapping best practices and working to align their approach for the coming year, Zager said. He’s hoping to incorporate further elements from West Side Collaborative into the school, pointing to student-led conferences as one example.

“It’s been a great experience,” Zager said. “When it comes to it, I now have more children, and I have more staff, all of which I love. I think they are great additions to the community.”

But some parents at the school raised concerns over whether the city’s Education Department had allocated enough resources to properly support the newly merged community, and alleged communications at the time of the merger had been misleading.

Last spring, district officials indicated the merged school might be eligible to receive federal dollars to support low-income students, depending on its combined enrollment. But this year, when parents learned the school didn’t qualify — and that the federal funds were allocated based on enrollment numbers as of October in the prior school year — they questioned why district officials hadn’t made it clear from the outset. Parents also argued those figures didn’t account for newly arrived migrant students that both schools had taken in during the year. (During the last school year, West Side Collaborative qualified for the federal funds, but Lafayette didn’t.)

One parent at the school, who requested anonymity, praised the principal and his staff for “working hard with everyone to make both student bodies feel as one,” but worried the school might not have sufficient funding to support its increased enrollment, particularly as the city’s Education Department faces significant budget cuts.

“The challenges come with the fact that there are now larger classes, and more students at more diverse levels from both communities,” the parent said. “What I’m concerned about is that the DOE has taken the approach that once the merger is approved, they can move onto the next agenda item.”

Mesic, the former West Side Collaborative parent, transferred her son to West End Secondary School, though she said it has paled in comparison to the community they lost. She also helped other families navigate the transfer process, as unhappy parents sought to leave the merged community ahead of the school year.

In total, about 17 students from the former West Side Collaborative did not enroll in the merged school this year — or about a quarter of the incoming seventh and eighth grade classes.

Despite the challenges in the months that led up to the merger, Samuels believes it has been successful so far. He noted his office is in the same building as Lafayette, meaning he can watch students and staff interact each day.

“In a perfect world, we’d have had more time to engage,” Samuels said. “But the process and the outcome that we have had has really been a model for other people possibly to look at.”

Julian Shen-Berro is a reporter covering New York City. Contact him at jshen-berro@chalkbeat.org.