The first episode of P.S. Weekly focuses on one of the biggest education stories in New York City this year: the arrival of thousands of migrant students.

Officials estimate that more than 36,000 migrant students have enrolled in city schools over the past two years.

What challenges are these new students facing? And what are schools doing to support them? This student-reported episode explores these questions through conversations with students, educators, and a journalist who’s been covering the issue.

The first segment features an interview with Chalkbeat reporter Michael Elsen-Rooney, as he explains how schools have been supporting recently arrived students — and what the media has gotten wrong. With the city’s recent policy limiting migrant families to 60 days in shelters, it’s been hard on schools to figure out how to help. Elsen-Rooney said school officials are grappling with questions like: “Can we figure out transportation for them, or do they leave? And then they have to start over at a new school?”

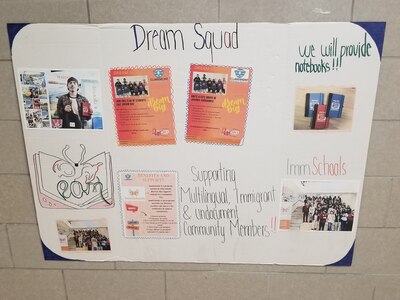

Next, Marisol Martin, a senior at Claremont International High School in the Bronx, talks about her hurdles and triumphs since coming here from Mexico a few years ago. As she’s gotten more involved with her school’s Dream Squad — a program the Education Department started in 2020 to help immigrant students and undocumented youth and is now in more than 60 schools — Martin has felt more a part of the community.

She’s paying it forward, now as a Dream Squad leader herself, and she shares her view on how schools should better help students feel connected to one another.

“What I would tell them is to socialize with other people,” Martin said in Spanish. “When you’re alone, you’re shy, and you don’t want to talk to anyone, you close yourself in your own world, and you don’t know more about what’s happening outside.”

Finally, Sunisa Nuonsy, a former high school teacher of 10 years at International High School at Prospect Heights in Brooklyn, talks about why she became a teacher specifically focused on immigrant students, the challenges she faced, and her advice to other teachers, especially those who are working with migrant students who may have experienced trauma. (Nuonsy is currently a doctoral student in urban education at the CUNY Graduate Center and a project researcher for the CUNY Initiative on Immigration and Education.)

“They can easily shut down and they can easily drop out,” Nuonsy said of migrant students. “So you have a very unique opportunity to be an adult in their life that is welcoming them and affirming them and showing them that they have value and that they should be here.”

P.S. Weekly is available on major podcast platforms, including Apple Podcasts and Spotify. Be sure to drop a review in your app or shoot an email to PSWeekly@chalkbeat.org. Tell us what you learned today or what you’re still wondering. We just might read your comment on a future episode.

P.S. Weekly is a collaboration between Chalkbeat and The Bell. Listen for new episodes Wednesdays this spring.

Read the full episode transcript below

Dorothy: Welcome to P.S. Weekly… the sound of the New York City school system. I’m Dorothy Ha, a senior at Stuyvesant High School– and I’m super excited to be hosting the very first episode of P.S. Weekly. This show is a collaboration between Chalkbeat New York, a leading education news site– and The Bell, a leading provider of audio journalism training to high school students. It’s a pairing as natural as a bacon, egg, and cheese!

Dorothy: Each week this Spring, our team will dig into one issue affecting New York City schools, bringing you a mix of voices and perspectives that you won’t find anywhere else. Along the way, we want to hear from YOU, our lovely listeners– more on that later in the show. Right now… let’s get to it.

Dorothy: For our first episode, we chose what’s been arguably the biggest story in New York City this year.

News Clip: Parents and educators say several Manhattan public schools are overwhelmed with an influx of migrant students. CBS News’ Natalie Duddridge spoke with the Chancellor on his efforts to find solutions.

Dorothy: What challenges are these new migrant students facing? And what are schools doing to support them? We’ll hear experiences directly from students and teachers. But first! We have Mike Elsen-Rooney with us. Mike is a Chalkbeat reporter who’s been covering how schools are responding to thousands of newly arrived migrant students.

Dorothy: Hi Mike! Thanks for joining us.

Mike: Hey, Dorothy. It’s great to be here.

Dorothy: All right. So, Mike, when did the issue that some have called the “migrant crisis” hit your radar?

Mike: So I remember back in Summer 2022, when this was first hitting the headlines. I was watching a meeting, and a superintendent said, “We’re expecting a couple hundred new students to come in.” And I was like, “Whoa, that seems like a lot of kids.” And then here we are about two years later, and it’s a whole lot more than that.

Dorothy: Right, so now it’s 2024. And how many people are we talking about in total now?

Mike: So our best estimate is that about 36,000 new kids have enrolled over the past couple of years.

Dorothy: Wow. That’s a lot of students. So what can you tell us about where these new migrants are living and where they’re going to school?

Mike: Yeah. So where they’re living really depends on where the city has been able to set up shelters. We’ve seen shelters pop up in Long Island City in Queens, and Clinton Hill in Brooklyn, and lots of different parts of the city. And so where kids go to school really depends on two things. Number one is how close it is to their shelters. The second thing is what schools are really good and well-equipped to serve English language learners.

Dorothy: I can imagine that there are a lot of challenges in handling this big increase in migrant students.

Mike: Yeah, it can be really hard just getting tons and tons of new kids with a lot of challenges. And then the thing that’s been really hard recently is that there’s this new policy: families can only stay in shelters for 60 days. After that, they have to reapply, and they may end up in a shelter in a different part of the city. And so schools have to figure out, “Can we keep this kid? Can we figure out transportation for them, or do they leave? And then they have to start over at a new school?”

Dorothy: Recently, you wrote a really interesting story about how this immigration issue is impacting students and how they’re feeling at this moment. And you spoke to folks at Newcomers High School. Can you tell us a little bit more about that?

Mike: Yeah. So Newcomers High School is this really interesting place in Long Island City, Queens. It’s been around for 30 years, and they’re really good at accepting newcomer kids from around the world and teaching them English and helping them get acclimated to life in the U.S. And so that school is also near a bunch of shelters in Long Island City. And so when I saw a couple of kids from Newcomers High School speaking at a meeting for the Panel for Educational Policy recently, I was really surprised by what they said.

Meeting Clip: Our name stigmatizes us and condemns us to always be patronized and not having a choice because we are “new.” We are marked with the idea that we are here occupying a space that is not ours.

Mike: They said that the name Newcomers High School was, quote, putting a target on their backs.

Dorothy: And so what happened after the testimony?

Mike: After that testimony, they went through the whole process of getting their name changed, and we just actually found out that they got approved to have a new name. And the school is going to be called Atlas.

Dorothy: The situation with their name change kind of makes me think about the portrayal of migrants in the media. You know, not every journalist is as thorough as you are, Mike. So what’s been the broader media narrative?

Mike: So we’ve seen some examples where the media actually has really not captured what’s happening on the ground. And one really good example is, there was an incident recently where the city had set up basically an emergency tent shelter on Floyd Bennett Field at the Southern tip of Brooklyn. And there was a storm coming, and the city decided to evacuate them.

News Anchor 1: Mounting frustrations this afternoon in Brooklyn after the city temporarily placed asylum seekers into the gym of James Madison High School in Midwood.

News Anchor 2: While the move was to provide shelter for them from last night’s storm, but it was meant– it meant that no classes happened at the school today. And parents are really frustrated by all of it.

Mike: The city had them stay there overnight and then got them out early in the morning. But the school’s principal decided, they weren’t going to be able to get it cleaned up in time; let’s switch to remote learning for the day. When this hit the news. It turned into this huge story, especially in a lot of right-wing media. And the narrative was that New York City kids are getting pushed out by migrant families. But when a colleague of mine actually talked to students and parents there, you know, kids were saying, “Look, we sympathize with these families. We didn’t want them to be exposed to any danger of being out in the storm. And it was just a very different set of reactions than what came through if you only read the kind of media firestorm over this. And so, you know, it kind of drove home this point that what the media says doesn’t always reflect the reality on the ground.

Dorothy: Wow, fascinating. And on top of that, immigration has been a big issue in the presidential election so far. I can think of one presidential candidate who has been speaking about it a lot in particular. So how has that impacted New York City?

Mike: So Donald Trump just weighed in on this. He made some claims in a recent interview that New York City kids were getting pushed out by migrant students. And it just is incorrect. And the biggest reason for that is that there are actually a lot of empty seats in New York City schools. We lost enrollment during the pandemic, and so there’s plenty of space and no one’s getting pushed out.

Dorothy: So my last question for you is, for educators, and policymakers, and community members who want to better support these migrant students, what are some of the success stories that you’ve seen?

Mike: So many schools have been finding really creative and empathetic ways to support their new kids. You know, one big example we’ve seen is that a lot of schools have done coat drives because a lot of these newcomer kids have lived in the Southern Hemisphere their whole lives and have never really been through a New York winter. So it’s just those kinds of things at the community level, listening to what these families need and making it happen.

Dorothy: Mike, thank you so much for sitting down and having this conversation with us.

Mike: Thanks so much, Dorothy.

Dorothy: And now, we’re going to take a closer look at what the experience is really like after students arrive here. And how one program is helping them adjust. Our P.S. Weekly reporter Jose Santana has the story.

Marisol: Hola, mi nombre es Marisol Martin. Soy del grado 12, soy senior, mi país es México.

Jose: This is Marisol Martin, an 18-year-old high school senior.

Marisol: The biggest challenge I have is the language. I only knew how to say “thank you.” The teacher back in my country told us “thank you” in English, but beyond that I didn’t know anything.

Jose: She arrived in New York City from Mexico when NYC schools were still remote because of the pandemic.

Marisol: It was very difficult for me to learn; ninth grade was very difficult. The classes were online, and that made it more difficult for me to learn, and I didn’t understand anything. I just used a translator or something like that to see what to do.

Jose: And she’s not the only one who faces these kinds of hurdles. New York City is a city of immigrants, and its schools reflect that. Young people from all over the world come here for a multitude of reasons. Last school year, nearly one in five city students was learning English as a new language. Here’s Governor Kathy Hochul during a press conference last September.

Kathy (News Clip): We have real challenges. They’re coming in from West Africa, South and Central America. So it’s not just assuming that Spanish is going to cover everybody. It doesn’t come close. City officials…

Jose: When high school students like Marisol first arrive in New York City, the school system typically enrolls them in one of about 20 international high schools. These are schools like Newcomers– now called Atlas –that specialize in supporting recent immigrants. Marisol attends Claremont International High School in the Bronx. Nearly all of its students are low-income and English language learners. When Marisol first got there, language wasn’t the only barrier.

Marisol: Another challenge for me was to use technology that was very complicated for me because they gave me an iPad to work with my things. But it was in English, and I didn’t know where to enter, what to do, or where to paste.

Jose: Being in a new country also takes some cultural adjustment.

Marisol: When I arrived here in the United States, I entered Claremont and I kind of didn’t have much connection with the people. Different countries, different cultures.

Jose: But lucky for Marisol– and so many other immigrant students –there was help.

Marisol: Something that has helped me are some groups, like the Dream Squad. When I entered tenth grade, I was on the Dream Team. That also helped me a lot to communicate.

Jose: What is a Dream Squad? To answer that question, come with me to one of their meetings. It’s 12 p.m. on a Tuesday and I’m here at the Dream Squad’s weekly lunchtime meeting in the school’s library. The Dream Squad’s staff director Evelyn Reyes is leading the meeting with about 10 students, who are all seniors. They were discussing plans and ideas to recruit more Dream Squad members by sending emails out, flyers and directly inviting students to their meetings. Evelyn said the program started in 2019 to help immigrant students and undocumented youth.

Evelyn: Our then social worker was working around creating a space where students, regardless of immigration status, could find, you know, that empowerment where their stories were shared.

Jose: Claremont is one of more than two dozen schools around the city with a Dream Squad program. Dream Squads receive support from the non-profit ImmSchools and the DOE’s Division of Multilingual Learners. They provide notebooks, laptops, lanyards, and events for students and staff. But the most important aspect of the program is the community itself– and the knowledge that gets shared. Meeting topics vary from week to week.

Evelyn: So, mental health, we want to talk about also “know your rights.” So that our students are aware of what their rights are as immigrants. We want our students to also know that they have different options when it comes to post-secondary planning, whether that is college, whether that is trade school, whether that is a certificate program. We do try to do our best to share the information that we share with the students inside those meetings, across the school.

Jose: Dream Squad is tackling some big challenges, and it’s not without its difficulties. Language continues to be an issue.

Evelyn: Claremont is a very multilingual school, so we are a very diverse school community. And sometimes, just being able to produce or communicate a lot of the resources on students’ native language, that could be something that can be a little bit challenging.

Jose: But, despite these challenges, Evelyn makes sure to let the students know that–

Evelyn: Your background, your values, your culture, all of that is an asset. Like you have that, value that. So I do want them to feel like their story matters. Like I want them to, to feel like they’re at a community. That they’re welcome not only inside our school community, but also, you know, in this country.

Jose: And how does Dream Squad measure success?

Evelyn: Knowledge is success for me. Like, as long as we’re about to reach our students and we’re able to provide the resources, that they know how to use the resources, that they know how to access those resources. That’s how we measure success.

Jose: After benefiting from the program, Marisol became a Dream Squad leader– for 2 years now –to help other students like her. I ask Marisol how she’s adjusted since arriving in New York 3 years ago.

Jose (in Spanish): After 3 years of being here, how have you adjusted?

Marisol: I think that through time and things around me, I was able to connect more with the things in the United States. And also how the people that I met helped me too, like… like my classmates who are also migrants. So, we talk to each other and tell each other about this and this. I think that was something that helped me a lot to adapt here.

Jose: I ask her what advice she’d give to other students who have just arrived and gone through a similar experience.

Marisol: What I would tell them is to socialize with other people. That’s very good, because having a connection to more people, you can know more things versus when you’re alone, you’re shy and you don’t talk to anyone. You close yourself in your own world, and you don’t know more about what’s happening outside.

Jose: And what can the schools do to make the experience better?

Marisol: I think that giving them guidance, telling them, like, “here you can learn, here you can communicate.” The schools need to have more– like a connection with students, because many of the children don’t know what to do when they arrive the first day. They are very shy, and I think that they should have more priority with them when they immediately arrive.

Jose: There’s no doubt that the increase in new students to the city creates a difficult situation for both the city and the students. But as Marisol suggests, there are things that can be done to make the immigrant student experience better. And it all starts with a supportive community– grassroots efforts like the Dream Squad program that are making schools a safe and welcoming space for all.

Dorothy: Once again, that was Jose Santana, reporting from Claremont International High School. We’re going to take a short break, but when we return… a teacher’s perspective.

Sunisa: Sometimes, students are hopeless. Which I think to a teacher, to see a hopeless student is sad; it’s heartbreaking.

Dorothy: So stay tuned…

Salma: Hey, listeners! We hope you’re enjoying the first episode of P.S. Weekly. We’ve got an assignment for you—follow us on Instagram @bell.voices. And we want to hear from you! Reach out to P.S. Weekly at psweekly@chalkbeat.org with comments, questions, and suggestions. And… if you want more student-created content, listen up!

Student 1: On Our Minds is a podcast about the teenage experience. Made by teens, for teens.

Student 2: There’s a lot on our minds, and talking about it helps.

Student 1: On Our Minds: Season 4 is produced by PBS NewsHour Student Reporting Labs, in collaboration with KUOW’s RadioActive Youth Media.

Student 2: Listen wherever you get your podcasts.

Dorothy: In the last segment, we heard about the immigrant student experience. When it comes to helping these students overcome language barriers and navigate a new environment, that job often falls to… you guessed it… teachers. Our producer Bernie Carmona spoke to one of them.

Bernie: As a child of immigrants, I’ve thought about the experiences of migrant students navigating through school life. But who takes on the responsibility for making sure students are fully prepared for their future? What do teachers go through while navigating classrooms with migrant students? I remember speaking to my older sister, Mariana, who moved from Mexico to South Carolina in 2002 when she was about 5 years old. She didn’t know English when she arrived and struggled to adjust to the new environment. She didn’t feel supported until she came to New York City, where she experienced the diverse culture and language in schools, things she couldn’t access in South Carolina.

Bernie: Her experience made me wonder: how does all of this look from a teacher’s perspective? I spoke to Sunisa Nuonsy, a former high school teacher of 10 years at International High School at Prospect Heights in Brooklyn.

Bernie: Thank you so much for being here, Sunisa.

Sunisa: Thank you so much for having me.

Bernie: Sunisa, why did you choose to become a teacher?

Sunisa: I became a teacher, particularly for immigrant students, because of my own experience. My family came to the U.S. as refugees from Laos. And sadly to say, some of my aunts and uncles, who were adolescents at the time of resettlement here, they were not equitably served in schools, and they dropped out of school. And so I always carried that with me. And when I became an adult, and I was thinking about my career path, I was very much drawn to language and to working with immigrants just because I felt like I could connect with them.

Bernie: Can you tell me a little more about how that experience was like for you?

Sunisa: The first time that I entered the school, I was interviewing as a student teacher, and I saw the students, and the different kinds of clothes they were wearing. Some kids were like, you know, dressed very Western, some kids were wearing more cultured clothes, hearing different languages. I thought it was the coolest place ever because I was like, “Look at these beautiful kids.” They come from everywhere. But we’re in Brooklyn. They’re so fly, they’re so fresh. It’s like where roots are– are like bursting through the ground, you know, because everything is just alive. Like the ways that language comes together, right?

Sunisa: I worked at a school, I would say was mostly Dominican. So every student learned Dominican Spanish, right? Whether you were from Yemen or Guinea, everybody was like, “Que lo que.” And just the way that our students were so open with their cultures and playing with one another’s cultures and really learning with it was just this beautiful hybrid space. And I don’t want to romanticize it, but I just imagine that that’s what our world could really be like is, you know, a place where people feel affirmed in who they are, but also aren’t scared to get to know other people. But we’re trying to make the world better, right? We’re trying to make people freer, more liberated. So I love that space. I love that liminal space.

Bernie: What would you say has been the biggest challenge you face with working with migrant students?

Sunisa: Well, I can say that although I identify as an immigrant myself, it’s such a tough situation to be in, and the larger administration is not aware of that. And they’re expecting you to be this robot that just has to do their job and perform their functions. But a lot of times I’ve seen it impossible to get a student to respond to classwork because they have so many other pressing and urgent issues that are just surrounding their brain and their souls. And that can be challenging to do when you have students who don’t see a pathway to college, they don’t even see a pathway to graduation. So to work with students, try to instill in them some sense of agency and empowerment, you know, even in the smallest ways, I think is really important because sometimes students are hopeless, which I think to a teacher, to see a student hopeless is sad. It’s heartbreaking, right, because you think that you’re there to really guide them to all of these opportunities when those opportunities are inequitably distributed. Like I think about college tuition, right, and financial aid and who can access financial aid and who can’t.

Bernie: What was a difficult moment you encountered?

Sunisa: I had two amazing students who were sisters, and they wanted to go to college. And their dad, culturally, didn’t think that college was for them. And so I had just so many conversations not only with them but with their guardians, with administrators at the schools, with other teachers. And oftentimes, I would just go back to my classroom and cry out of frustration because you could feel like you’re doing all of the hard things that you need to do to support these immigrant students. And there are still things that are just out of your control. So to see these students who had come all this way, had come from this village in Yemen to Brooklyn. And really learn how to believe in themselves and have some empowerment and still not be able to make that one crucial decision about whether they can continue their educations. It’s just, you know, I don’t know, even know how to troubleshoot that.

Bernie: Do you have any advice for teachers that are currently working with migrant students?

Sunisa: My recommendation for all teachers really is to know who your students are. Get to understand their context and their experiences before you label them as anything. Because, especially immigrant students, the ones who have experienced trauma along the way, they can easily shut down and they can easily drop out. So you have a very unique opportunity to be an adult in their life that is welcoming them and affirming them and showing them that they have value and that they should be here.

Bernie: Thank you so much for being a part of this interview, Sunisa.

Sunisa: Thank you so much for having me.

Bernie: I’m Bernie Carmona, reporting for P.S. Weekly.

Dorothy: That’s it for our first episode, but before you go, we have an extra credit assignment for you! Go to chalkbeat.org/newsletters, or click the link in our show notes, to sign up for the Chalkbeat New York morning newsletter. It’s the best way to stay informed on local schools coverage Monday through Friday. And if you really want to impress the teacher, drop a review in your podcast app or shoot an email to psweekly@chalkbeat.org. Tell us what you learned today or what you’re still wondering. We just might read your comment on a future episode.

Dorothy: P.S.: We’re back next Wednesday with an episode on how the national wave of Book Bans is impacting local schools.

Preview Clip: These groups are trying to erode the trust of educators in general by placing doubt in people’s minds about what a teacher is exposing kids to, is really just trying to attack the public school system.

Dorothy: Until then… [with entire cast] class dismissed!

CREDITS

Dorothy: P.S. Weekly is a collaboration between The Bell and Chalkbeat, made possible by generous support from The Pinkerton Foundation, The Summerfield Foundation, FJC, and Hindenburg Systems. This episode was hosted by me, Dorothy Ha. Producers for this episode were Sanaa Stokes, Jose Santana, and Bernie Carmona. With reporting help from Chalkbeat reporters Alex Zimmerman and Mike Elsen-Rooney. Engineering support was provided by Ava Stryker-Robbins. Our marketing lead this week was Santana Roach. Our executive producer for the show is Joann DeLuna. Executive editors are Amy Zimmer and Taylor McGraw.

Additional production and reporting support was provided by Sabrina DuQuesnay, Mira Gordon, and our friends at Chalkbeat. Special thanks to our interns Miriam Galicia and Makenna Turner. Music from Blue Dot Sessions and the jingle you heard at the beginning of this episode was created by the one and only: Erica Huang.

Thanks for tuning in! See you next time!

Correction: The Dream Squad, which started in 2020 is now in 60 schools, up from 25.