This episode of P.S. Weekly takes a look at how a national wave of book bans has been coming ashore in surprising ways in New York City.

Between 2021 and 2023, there were nearly 6,000 instances of books being banned across the country, according to PEN America, a group that defends writers and protects free expression. Nearly 60% of these books were young adult books written for school-age kids.

New York City schools have not banned books, but recently got a taste of this controversy when books that touched on themes of Black history, immigration, and transgender identity were discovered in the trash near a Staten Island school, sparking an investigation, according to Gothamist. But educators here had already been embroiled or engaging in the national conversation around book bans in other ways.

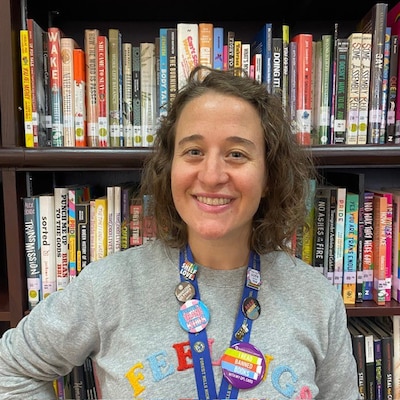

This episode’s first segment features a school librarian who in 2022, after using social media to promote LGBTQ books during Pride month, faced an onslaught of vitriol and harassment online.

Lindsay Klemas, who was the librarian at Forest Hills High School in Queens at the time, said the incident took a toll on her mental health. She worries about the broader implications such attacks could have on educators and public schools.

“A parent has the right to say for their own kid what they can read. It does get murkier as you become a teenager,” said Klemas, who is now the coordinator for all Queens public school libraries. “But I also think that these groups are trying to erode the trust of educators in general, and so I think by placing doubt in people’s minds about what a teacher is exposing kids to is really just trying to attack the public school system.”

The show’s second segment looks at a Queens high school that has created a sophomore English class devoted entirely to books that have been banned elsewhere.

Amy Weidner-LaSala, who teaches the course at the Academy of American Studies, said the books they’re reading can help show students “how we open our minds and accept new things through literature.”

P.S. Weekly is available on major podcast platforms, including Apple Podcasts and Spotify. Be sure to drop a review in your app or shoot an email to PSWeekly@chalkbeat.org. Tell us what you learned today or what you’re still wondering. We just might read your comment on a future episode.

P.S. Weekly is a collaboration between Chalkbeat and The Bell. Listen for new episodes Wednesdays this spring.

Read the full episode transcript below

Sabrina: Hey listeners, save the date! We’ll be having a virtual Zoom event on April 17 from 5-6 p.m.

It’s called Inside P.S Weekly: Meet the students and adults behind the new podcast

Join us on Zoom and learn how the podcast is made, how it can be used as a teaching tool, and how you could potentially have your voice, heard, on the show.

Check out the link in our show notes! Keep listening to hear the rest of this episode!

Tanvir: Welcome to P.S. Weekly… the sound of the New York City school system. PS Weekly is a collaboration between Chalkbeat New York and The Bell.

Tanvir: I’m your host this week, Tanvir Kaur. I’m a senior at Academy of American Studies in Queens.On today’s episode: how the national wave of book bans is showing up in New York City in surprising ways.

But first! A Chalkbeat news bulletin…

NEWSBRIEF

Alex: I’m Alex Zimmerman, a reporter with Chalkbeat. Here’s a quick recap of the past week’s biggest education stories:

City officials are replacing metal detectors at nearly 80 campuses with new ones designed to let students keep their backpacks on instead of sending them through a separate x-ray machine. But the city will still make students take off their backpacks — raising questions about the $3.9 million upgrade.

Roughly 139,000 families applied to Summer Rising, the city’s free summer school program — that’s far more than the number of available seats. The program remains popular, even as Mayor Eric Adams has cut back middle school hours to save money.

And on Monday, April 8, a total solar eclipse is coming to parts of New York State. Several schools are hosting watch parties, as is the New York Hall of Science in Queens.

To stay up to date on local education news throughout the week, go to chalkbeat.org/newsletters and sign up for the New York Daily Roundup.

Tanvir: Last year, Texas Governor Greg Abbott signed a bill banning books that contain violent, sexual, or sensitive content. Similar bills in other states have affected even more children’s schools and libraries.

Tanvir: Between 2021 and 2023, there were close to six thousand recorded book bans across America. Of these banned books, nearly 60% were young adult genres. Meaning, books written for school-age kids are being targeted.

Tanvir: I had heard about this trend, and it troubled me. I thought–At least, this isn’t happening here… But then…

NEWS CLIP

Reporter 1: An investigation underway this afternoon after some books were thrown out into the trash at a school on Staten Island.

Reporter 2: Now the books are about Black history and the LGBTQ community, and all were found with notes attached to them, critical of both. Eyewitnesses…

Tanvir: The Department of Education is currently investigating the incident in Staten Island — which appears to be an isolated case — but it’s a reminder that NYC is not immune to the national attempts to censor what students read and learn in school.

Today, we speak to a school librarian who used social media to promote LGBTQ+ books during pride month... and then experienced wrath online from parents across the country.

Then: how one Queens school is flipping the narrative on its head… embracing the books that some districts have deemed too dangerous to read through a course entirely devoted to them.

Our PS Weekly producer Salma Baksh has our first story…

Salma: I’m here with my school’s former librarian, Lindsay Klemas. We call her Ms. K. Let me tell you: the students at Forest Hills High School were devastated last year when she left. But we were also happy for her. She’s now the Coordinator for all Queens public school libraries.

Salma: I met Ms. K in my sophomore year. She quickly became my go-to person for basically anything – decision-making, emotional support, and book recs (obviously). Students knew her as empathetic and kind, making the library a true safe space.

Lindsay: I became a librarian in 2010. I started my career at a high school for students with emotional disabilities in the Bronx, and I worked there for about six years. And then I was at Forest Hills High School for a little over seven years.

Salma: What made you want to become a librarian?

Lindsay: I decided to become a librarian because librarians are pathological helpers and we like to give people information, make people feel welcome, and make sure that people can sort of have a third space they can go to.

Salma: What is your definition of librarianship?

Lindsay: A librarian, to me is someone who is able to allow others to see themselves on the shelves. So I think a good librarian is able to have books and resources that all of their patrons want to access, but it’s a place where people can be themselves and also find information or stories that speak to them.

Salma: Have there been any instances, any negatives that have arisen out of the way that you fulfill your definition of what it means to be a librarian?

Lindsay: Yes. In the fall of 2022, I actually became a victim of some online harassment. Um, It happened because our school library Instagram page was discovered by a group of people who didn’t like the books that I featured in a reel that we had made for Pride Month. And so people started to say that the book should be put in the woodchipper, that I should be fired. I was a pedophile. this was in reference to the book that’s called “This book is Gay,” which has received numerous starred reviews from professional reviewers and is considered an important book for teenagers, but is also a very banned and challenged book nationwide.

Salma: So receiving that kind of hate from people that don’t even know you must have been very heavy on you and your mental health. How did you react?

Lindsay: It was definitely heavy on my mental health. I feel like I’m still sort of processing slash. I’ll think to myself, “Did that even happen?” Or there might be conversations about book banning and people say, “Oh, that doesn’t happen in New York City schools.” And you’re like, “Wait, it happened to me.” And then you’re sort of in this situation where you’re deciding, “Do I bring it up and tell what happened? Or is that centering myself in the story when really the story is that kids deserve access to materials?” So I was sort of like, what stories do I turn to or what can I learn from this and how do I move forward? And I felt like there wasn’t really a road map for that. And so it was difficult for sure.

Salma: Have you heard of other incidents of librarians getting this kind of response?

Lindsay: I haven’t heard of any school librarians receiving as much vitriol as I did in my situation, but I know that there are New York City school educators who either feel like they can’t be their true selves at work because of their gender identity or their sexual orientation. There are teachers who have had parents question what they’re teaching, or there may be librarians who or, you know, E.L.A. teachers who sort of self-censor. That would look like saying, well, I don’t want to make waves or become a potential victim to people who are trolling. So I’m going to not teach that book or I’m going to not purchase that book for our school library collection. And so that’s a way that the censorship wars can impact people, subconsciously.

Salma: In this conversation of deciding if a book is appropriate, what role do you think parents play?

Lindsay: I think a parent has the right to say for their own kid what they can read. I think it does get murkier as you become a teenager. But I also think that these groups are trying to erode the trust of educators in general and so by placing doubt in people’s mind about what a teacher is exposing kids to, is really just trying to attack the public school system. And, I think we need to show parents that they can trust the education specialists to decide what is appropriate for their own child.

Salma: Ms. K believes that schools, by giving access to these challenged books, help students figure out who they are.

Lindsay: There are kids right now who might be in a really great school and they might hold it together during the school day. But then at home, they might have to hide their gender identity or their sexual orientation from their families, and they don’t have a safe space at home. And I think it’s just so important for kids to be able to be who they are and to have a space to figure out everything about who they are. And libraries can be that space.

Salma: This is Salma Baksh reporting for PS Weekly.

Tanvir: We’ll be back after a short break…

Sabrina: Hey listeners! We hope you’re enjoying this episode of PS Weekly.

We’ve got an assignment for you– follow us on Instagram @bell.voices. And, we want to hear from you! Reach out to P.S. Weekly at the email address: psweekly@chalkbeat.org with comments, questions, and suggestions.

Tanvir: And we’re back…

Tanvir: While some school districts around the country are banning books they think are inappropriate for students–one class at my school is putting those books on its mandatory reading list. I helped our reporter Shoaa Khan report the story….

Shoaa: Picture this: a stack of books that contain themes of race, LGBTQ identity, and sexual content… that have been banned elsewhere. But in this classroom, 10th graders are cracking them open.

SCENE TAPE of Banned Books Class:

OK folks if we can put our phones and your numbers–if you need your number let me know…

Shoaa: This is sophomore English at the Academy of American Studies. The class centers on banned or challenged books. I had to know more.

Shoaa: Our host Tanvir spoke with Amy Weidner-Lasala who teaches the class.

Shoaa: Ms. Weidner-Lasala’s classroom feels lively, as students stroll into class after the bell. They come in, greeting each other, engaging in small talk, shuffling in their clustered desks until it’s time for Ms. Weidner-Lasala’s instructions.

SCENE TAPE of Banned Books Class :

Ok folks, we’re going to spend today and tomorrow working on an argumentative essay for the regents…

Shoaa: She says It all started with a conversation with the school’s principal Mr. William Bassell

Amy: I think with the current events within the last couple of years, Mr. Bassell thought it would be a really interesting class to offer, and I think at first we were just going to offer it as an elective. But then he decided to sort of open that net a little wider to reach the whole 10th grade.

Amy: There’s a variety of books that we can teach, but I teach Night. I teach the Joy Luck Club. I teach Animal Farm, even though 1984 was also an option, which, you know, more explicit. Again, it’s an older book, but it still deals with that like censorship and banned books-ness, and control. So Orwell, it’s very popular.

Shoaa: If students feel upset about a particular book, they can choose to read a different one. But Ms. Weidner-Lasala says it takes away from the class experience and from participating in interesting group discussions and perspectives.

Amy: I think it opens their minds and lets them see that maybe like even what we think now is like not a big deal can be seen as a big deal to some people. And like how viewpoints and, change historically and how we open our minds and accept new things through literature.

Shoaa: A few years ago, the New York City Department of Education launched a new initiative called “Mosaic” to help expose students to diverse topics, including Black studies, Asian American and Pacific Islander Studies, and LGBTQ experiences.

The DOE sent more than FOUR MILLION books to diversify library shelves at schools across the city. The books found in the trash of the Staten Island school that we heard about earlier were part of Mosaic.

Amy: It’s supposed to show a mosaic of experiences, I guess. So a lot of the books have main characters or authors who are people of color, who are African-American, who are LGBT, you know that fit into sort of like a non-straight white man lens. So it allows students to see different perspectives and read different books that maybe wouldn’t fit in the traditional curriculum.

Shoaa: We asked Ms. Weidner-Lasala why she thinks some adults want to censor what students read.

Amy: I think a lot of times it comes out of fear and the fear of schools taking over values that maybe parents and the community don’t necessarily share, and that wanting to protect kids. I think it comes from a good place a lot of the time. But I think it’s often mis-done.

Shoaa: And how do students feel about the curriculum? Are they enjoying the class?

Drew: I’m Drew Mercado. I’m a sophomore and I currently take Banned Books 10. And I think this class is very interesting because it actually embraces what the government wants to be censored, and I think it’s a very unique experience and it’s a unique way of learning and honestly, I myself and I think the teacher also find the material really fun to learn. Honestly, this is probably one of the classes I look forward to the most. Not only because my friends are here, it’s because, yeah, what I’m going to learn next.

Shoaa: Tanvir also spoke to Tabassum Akter, a sophomore in the Banned Book class.

Tabassum: We read The Lord of the Flies, I think it was really interesting to learn about human nature because it’s something we discuss a lot in the class. It’s reflected in most of the texts that we’ve read, and we’ve done a lot of argumentative essays as well on the subject of morals. So I think something I’ve taken from my classes to always be a good person regardless of the situation.

Tanvir: Has there been anything special about this class compared to other English classes or other classes in general that you have taken?

Tabassum: It makes you think about the world more. Like you have to understand and connect to the world through the books you read. And I think Banned Books helps you do that because these books were books that you weren’t allowed to read at one point, and now we’re allowed to read it. And it’s important to know why they were banned and why they should be read.

Shoaa: So, should books be banned?

Tabassum: No, of course not, because any form of literature should be allowed to be read. Whether it’s bad literature or intense literature, we should be able to analyze it because it was created for a reason.

Shoaa: Books are incredibly important for sharing ideas and perspectives. Learning should include all kinds of viewpoints and stories, not just what people like or dislike. And this course puts these issues front and center, giving students the chance to decide for themselves what to take from these books. The class, according to the course description, “lends itself to complex and thought-provoking conversations about power, freedom, and social and cultural values.”

To me, this course provides something all students deserve: the freedom to explore and express ourselves fully.

Tanvir: Once again, that was Shoaa Khan for a piece we reported together at my high school, the Academy of American Studies.

Tanvir: That’s all for today, but before you go, here’s your extra credit assignment.

We want to hear from you. What’s your favorite book you read in school? It could be a banned book or not — just tell us the title, author, and what it taught you. Email your answers to psweekly@chalkbeat.org. We might give you a shout-out in a future episode.

And P.S. We’re back next Wednesday with an episode about special education, that you don’t want to miss.

Preview clip

Kaiya: I know it’s special education, but they look down on us, like there’s something wrong with us, or like we’re… disgusting.

Tanvir: Until then… class dismissed!

CREDITS:

Tanvir: PS Weekly is a collaboration between The Bell and Chalkbeat, made possible by generous support from The Pinkerton Foundation, The Summerfield Foundation, FJC, and Hindenburg Systems.

This episode was hosted by me, Tanvir Kaur.

Producers for this episode were: Salma Baksh, Shoaa Khan, and Me Tanvir Kaur, with reporting help from Chalkbeat reporters Alex Zimmerman and Mike Elsen Rooney.

Engineering support was provided by Christian Rojas-Linares

Our marketing lead this week was Marcellino Melika

Our executive producer for the show is JoAnn DeLuna

Executive editors include Amy Zimmer AND Taylor McGraw

Additional production and reporting support was provided by Sabrina DuQuesnay, Mira Gordon, and our friends at Chalkbeat.

Special thanks to our interns Miriam Galicia and Makenna Turner and all of our wonderful volunteer mentors.

Music from Blue Dot Sessions and the jingle you heard at the beginning of this episode was created by the one and only: Erica Huang

Thanks for tuning in! See you next time!