Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to keep up with NYC’s public schools.

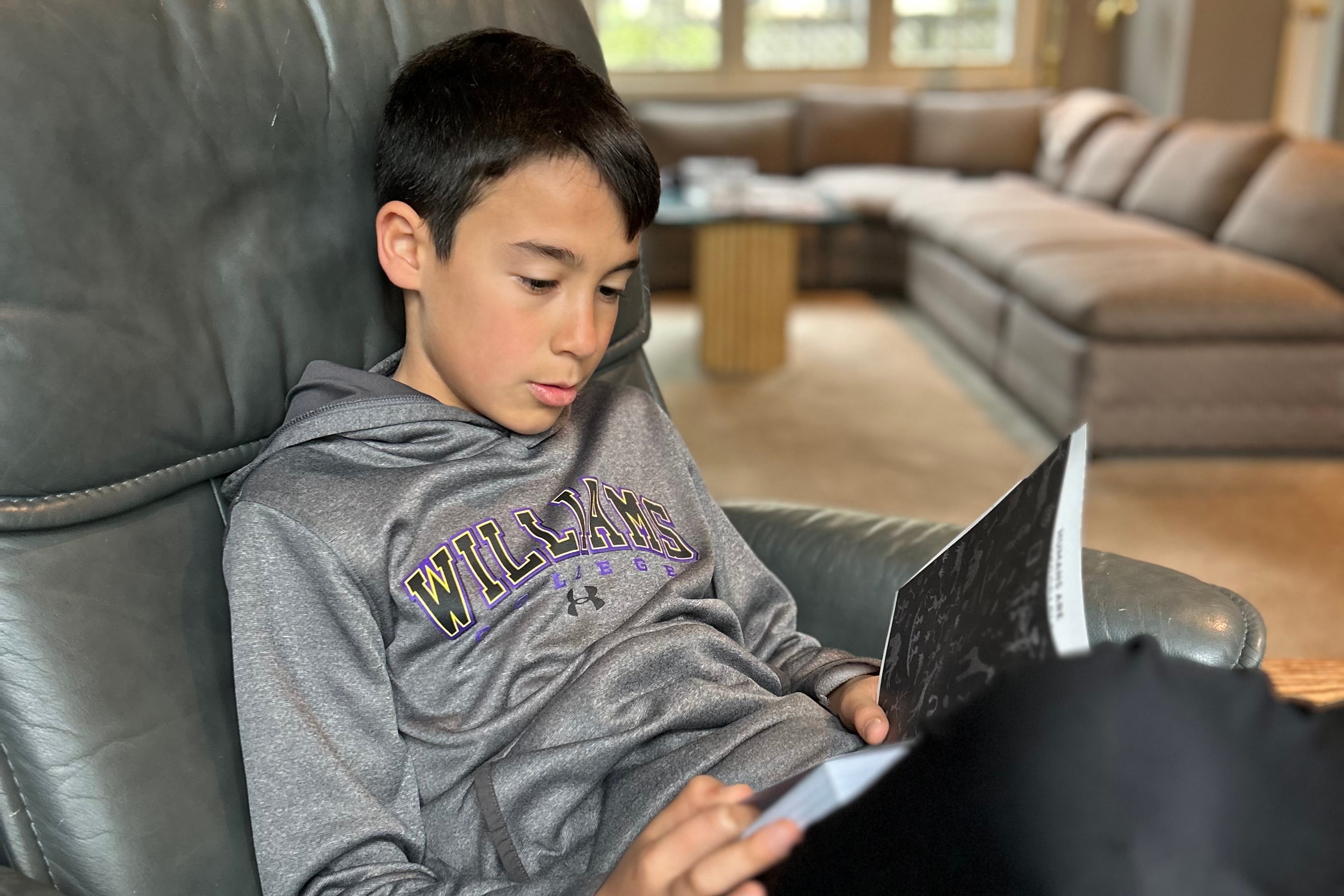

Twelve-year-old Carlo Murray perched on his tiptoes to reach the microphone as he addressed education officials last month. He then unleashed a withering critique of his school’s reading curriculum.

“I love to read all sorts of books,” Carlo told the city’s Panel for Educational Policy, a group that approves contracts and other school policies.

But this year, his teachers are focusing on short passages, leaving him frustrated and bored.

“It feels like I’m getting half an ELA sixth grade experience, half the story, half a piece of writing, only half a curriculum,” Carlo, who attends the Brooklyn School of Inquiry, often called BSI, said to applause.

One by one, Carlo and a handful of his classmates took turns at the microphone to bemoan their experience with the school’s new literacy curriculum. Educators at BSI, along with elementary schools across the city, have been required to adopt one of three reading programs, part of a mandate under schools Chancellor David Banks to boost literacy rates by flushing out popular but increasingly discredited programs.

The BSI students’ strong reactions are notable in part because there has been little organized opposition to the reading curriculum overhaul, as many literacy experts, the city’s teachers union, and several major education advocacy groups have supported it.

But resistance may grow louder as the city has required all local districts to adopt the new reading programs by September, up from just under half this school year. Some parents and educators at schools gearing up to use the new reading materials this fall have started speaking out, arguing the curriculum changes could threaten to upend the project-based learning or teacher-created curriculums that make their schools distinctive.

“Phase two is going to be harder than phase one,” said Susan Neuman, a New York University professor and member of the city’s literacy advisory council. A handful of wealthier districts that also tend to post higher test scores than average — including Districts 2 and 3 in Manhattan and Brooklyn’s District 15 — are all part of the second phase. “It’s going to be very interesting to hear how they respond,” Neuman said.

Most popular curriculum is getting most of the criticism

The reactions at BSI could serve as a preview of worries starting to bubble up elsewhere.

Much of the criticism of the curriculum overhaul has focused on the program that 22 of the city’s 32 local superintendents are requiring in their elementary schools: Into Reading, from the company Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, also known as HMH. The remaining districts are either using Wit & Wisdom, from a company called Great Minds, or EL Education.

Unlike the other two approved curriculums, HMH is built around an anthology-style textbook that includes passages designed to teach reading skills. Experts say the curriculum may feel easier for educators to quickly unpack than the other options, and it also includes a Spanish-language version. One review faulted the curriculum for not being culturally responsive, which sparked considerable criticism, though HMH has disputed the findings.

To some students at BSI, a gifted K-8 program with competitive admissions and reading proficiency rates that topped 90% last year, their main worry is that the new curriculum feels like dry test prep.

Adding to the concern, the local superintendent that oversees BSI has required middle schools to use HMH, a step further than the citywide requirement to use an approved curriculum in grades K-5 — though more schools may be soon heading in that direction. Banks has pledged to overhaul curriculums across a range of other subjects and grade levels, including high school algebra, a process that is drawing mixed reactions.

Sixth grader Penelope Naidich said her reading classes now draw on shorter texts that come from the HMH workbook rather than teacher-designed classroom conversations of full books. Last year, “we had a whole class discussion, like what happened in the chapter, how did it relate to the theme and the plot,” Naidich said in an interview. “The deeper stuff you’re not getting from these excerpts.”

Still, students and parents at BSI said teachers have recently had more freedom to teach full books, though not as many as in previous years. A representative for HMH wrote in a statement that the curriculum materials for middle school grades includes “numerous complete selections, long reads and novels, in addition to excerpts” and the program “is designed to be flexible so that educators can make decisions that best serve their students.”

The school’s principal did not return a request for comment.

Top education officials contend the curriculum overhaul is essential because the city’s traditional approach of giving schools freedom to pick their own materials has produced meager results: Roughly half of the city’s students in grades 3-8 are not considered proficient in reading, according to state tests.

Banks has laid much of the blame on “balanced literacy” programs, including a popular one created by Teachers College Professor Lucy Calkins. That curriculum encourages students to independently read books at their individual reading levels, an approach meant to foster a love of literature but which experts say is less effective for struggling readers who need systematic instruction. Teachers were also encouraged to use discredited strategies like using pictures to guess at words.

Neuman, the NYU professor, applauded the city’s efforts to move away from balanced literacy and reign in the hodgepodge of approaches schools have used. But she acknowledged some tradeoffs. “The whole idea behind this initiative is to lift the boats of the kids who have been traditionally left behind, and that means some of the advanced students might be subject to a simpler program,” she said. “Right now, that’s the cost.”

City officials initially indicated that a small slice of schools with reading proficiency rates above 85% could be eligible for waivers from the mandate — and some BSI parents have pressed for one. Education Department spokesperson Nicole Brownstein said some schools sought waivers, but ultimately chose to use their district’s required curriculum. She declined to elaborate on the process for granting waivers or if the city abandoned plans to consider them for schools with high test scores.

Reading instruction shift worries some parents in next phase

Beyond BSI, some educators and families at schools that are gearing up to implement new reading curriculums in September are also raising alarms.

Alex Estes, the parent association president at The Neighborhood School in Manhattan, said he’s concerned about the new curriculum’s impact. The school, which is in District 1, will be required to use EL Education in September.

With lots of material to cover in the new curriculum, Estes worries educators won’t have time for lessons they’ve prioritized in the past. The school has a particular focus on creating a welcoming environment for LGBTQ students and staff, including a social-emotional curriculum that delves into age-appropriate discussions of gender identity and pronoun use. Estes fears that the school will have to make difficult tradeoffs to make room for the new materials.

“If we take EL’s curriculum 100% and follow it to the T, it is not theoretical that we will lose time for our homegrown curriculum like our identity unit,” Estes said. “There are only so many hours in a school day.”

At a recent Community Education Council meeting in District 15, which stretches across a handful of neighborhoods from Park Slope to Sunset Park, some caregivers echoed that they were happy with their schools’ current approach to instruction.

District 15 will require schools with dual-language programs to use HMH. All others will use Wit & Wisdom, a curriculum known for building students’ background knowledge and lengthy units on non-fiction topics.

“Mandates in general don’t necessarily acknowledge what’s going well,” said Lauren Monaco, a parent at The Brooklyn New School, a campus that often bucks traditional mandates including state testing in favor of student presentations of deep dives into various topics. “I don’t want the baby to be thrown out with the bathwater.”

In response to families at the meeting, District 15 Superintendent Rafael Alvarez suggested teachers won’t be expected to implement every element of the curriculum right away and said there will still be time for independent reading.

Alvarez also indicated District 15 will have more leeway to implement the curriculum gradually compared with Brooklyn District 19, which includes East New York and used the Wit & Wisdom curriculum districtwide even before the new mandate.

One reason for the added flexibility is their differing demographics, he noted. The vast majority of children in District 19 are Black or Hispanic and from low-income families. About 38% are considered proficient in reading. In District 15, fewer than half of students are Black or Hispanic or live in poverty — and 63% are proficient readers.

“We have a different community,” Alvarez said. “It’s the reason why there’s flexibility around how we’re using the curriculum — because we don’t have the same demographics where all of our kids need it verbatim with fidelity every day.”

Many educators haven’t spoken out

Educators have largely not organized against the curriculum changes. But Emily Haines, a veteran literacy coach at The Laboratory School of Finance and Technology in the Bronx, is trying to change that. She recently launched a petition to drum up support for letting schools pick their own materials.

“Communities should have a voice in choosing a curriculum,” Haines said. Her school covers grades 6-12, but her local superintendent in District 7 has also required that middle schools adopt EL Education, the same program mandated across the district in grades K-5. (An Education Department spokesperson declined to say how many superintendents have issued similar directives for their middle schools.)

Haines said her school currently uses Calkins’ program. She worries the new materials will leave less time for narrative writing, one strategy she uses to get to know her students. And though she acknowledges exposing students to challenging books is important, she’s concerned the new curriculum will force her students to read longer books well beyond their reading levels. About 55% of her school’s students are proficient readers, according to state tests, compared with 32% across District 7.

The Bronx educator said she’s heard from teachers who have privately complained about the changes but, “for some reason it’s not translating into pushback.” So far, her petition has fewer than 100 signatures.

She suspects educators may see little value in speaking out and might be hoping for light enforcement of the mandates. Some principals have indicated plans to sidestep the curriculum requirements.

“I think people are just waiting,” Haines added. “Banks and Adams won’t be around forever and we can go back to what we’re doing before.”

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.