This episode of P.S. Weekly dives into New York City’s notoriously complex special education system, which serves 1 in 5 students — or more than 200,000 children.

Students with disabilities have the right to customized support — listed on individualized education programs, or IEPs, or 504 plans — that spell out what accommodations they need, from smaller classes to frequent breaks. But securing a learning plan, and getting the services listed on it, can be an uphill battle.

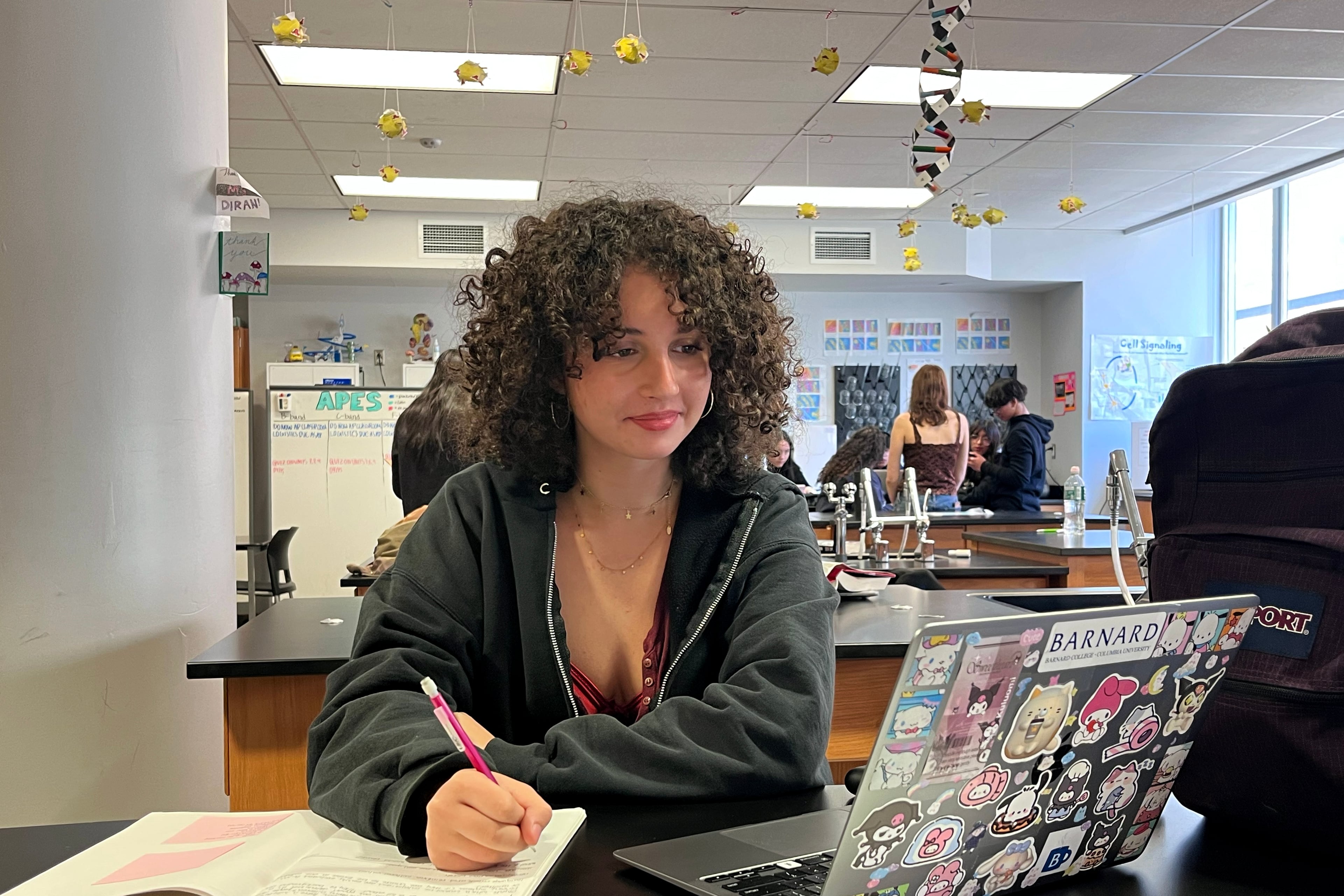

Our first segment focuses on those challenges through the eyes of two Beacon High School students who have a common accommodation: extra time on tests. Beacon senior Zoe Lazaros tells student producer Ava Stryker-Robbins that they faced a monthslong process to get that accommodation.

“I would not have gotten through my junior year without it,” Zoe says. “But I’m now realizing, like, so many people don’t have access to therapy or a psychiatrist or a parent that will stand up for them. And even with that, it was almost impossible for me to get [a 504 plan].”

Stryker-Robbins also digs into the stigma and trade-offs students can face when they try to use extra time, including missing out on classroom instruction.

Next, student producers Santana Roach and Dorothy Ha explore the broader experiences of students with disabilities through short-form interviews at Frederick Douglass Academy II Secondary School and Stuyvesant High School.

“Not everyone wants to be treated, like, differently,” one student says. “No matter of your race, or gender, or even if you have autism.”

P.S. Weekly is available on major podcast platforms, including Apple Podcasts and Spotify. Be sure to drop a review in your app or shoot an email to PSWeekly@chalkbeat.org. Tell us what you learned in this episode or what you’re still wondering. We just might read your comment on a future episode.

P.S. Weekly is a collaboration between Chalkbeat and The Bell. Listen for new episodes Wednesdays this spring.

Read the full episode transcript below

Sabrina: Hey listeners, save the date! We’ll be having a virtual Zoom event on April 17 from 5-6 p.m.

It’s called Inside P.S Weekly: Meet the students and the adults behind the new podcast.

Join us on Zoom and learn how the podcast is made, how it can be used as a teaching tool, and how you could potentially have your voice heard on the show.

Check out the link in our show notes!

Bernie: Welcome to PS Weekly… the sound of the New York City School System. I’m your host this week, Bernie Carmona. I’m an 11th Grader at The Beacon School in Hell’s Kitchen, Manhattan. I’m very excited to be hostingBernieing the third episode of P.S. Weekly! P.S. Weekly is a collaboration between Chalkbeat New York and The Bell.

Today we’re diving into an important issue… the struggle students with disabilities face in getting accommodations from their schools.

Bernie: But first the Chalkbeat Bulletin….

Mike: I’m Mike Elsen-Rooney, a reporter with Chalkbeat. Here’s a quick recap of the week’s biggest education stories.

A 4.8-magnitude earthquake shook New York City last Friday. Most schools were unscathed, but the gym at J.H.S. 218 in East New York, Brooklyn, was damaged and is temporarily closed. Officials said the rest of the building is safe.

Mike: Looming budget cuts this summer could jeopardize the jobs of 100 Education Department coordinators working in family homeless shelters. Advocates and families say that would be devastating when there’s a record number of homeless families and high rates of chronic absenteeism.

And there are 9 new public schools set to open in New York City this year. They include a new Bard Early College High school in Brooklyn and a high school in Queens focused on the motion picture industry.

Mike: To stay up to date on education news throughout the week, head to Chalkbeat.org/newsletters and sign up for the New York daily roundup.

Bernie: More than 200,000 students in New York City’s public schools have a disability classification–that’s larger than the ENTIRE city of Syracuse. These students are guaranteed a plan that lays out exactly what accommodations they need to learn; from a smaller class size to physical therapy. They’re called Individualized Education Programs–or IEPs. Others might have what’s known as a Section 504 plan.

504 plans are for students with disabilities who don’t need specialized instruction, but STILL need accommodations to learn. These accommodations can include sitting near the teacher, or having classroom breaks.

Bernie: Getting an IEP or 504 isn’t always easy. We drilled down into one common type of accommodation: extra time on tests. Our reporter Ava Stryker-Robbins found that students often face roadblocks and even unexpected consequences when trying to use their accommodations. She has the story…

Ava: Imagine you’re getting ready to take a test. You grasp your pencil and feel your heart beating as the teacher sets a timer.

Voice: Class, you may begin.

Ava: You hear the bustling movements of your class fade to silence. Everyone around you starts to scribble at a fast pace. And though you studied all night and knew the material through and through, you just can’t keep up. You try to stay focused. You try to go faster. But before you know it…

Voice: Time is up. Everyone put your pencils down.

Ava: You couldn’t finish as fast as everyone else; no matter how hard you tried. Zoe Lazaros, a 17 year old senior at the Beacon School, has had many similar experiences. Although they have ADHD, they went through school without any accommodations — like extra time — for many years.

Zoe: I think, at first, I had this kind of reassurance that, you know, I always kind of pulled through as a student, regardless if I was struggling in a class. And when that started kind of not working anymore, it felt very stressful. And also just generally helpless.

Ava: After years of constantly working long hours outside of school to stay on track, Zoe finally got their 504 two years ago during their sophomore year of high school. Getting it was not an easy process...

Zoe: It took probably around four months from the beginning of the process. Like, it wasn’t as long as I know some other people were, but it was definitely a draining process.

Ava: One of the first things Zoe had to do for their 504 application during the 2022-2023 school year was get on a Zoom meeting with their mom, their therapist, and a 504 coordinator at Beacon.

Zoe: There was a bunch of people kind of vouching for me and being like, you know, Zoe needs this. A lot of people don’t have that. So the fact that I had that and still it was difficult for me to get a 504 is really telling. So yeah, what ended up happening was we were on, like, this group Zoom call, and they said that they would not be able to give me a 504 cause my grades were too good. I felt very discouraged after that.

Ava: But a few months later, Zoe had to try again.

Zoe: I was failing three of my classes, and I wrote this very angry email to my 504 coordinator, and I was like, “Do you see my grades? I’m failing 3 classes. Will you help me now?” And she responded back to me and she’s like, “Yes, let’s have a meeting.” And I was like, “Girl…” It took me failing 3 of my classes, and my therapist, and my psychiatrist, and my mom, and like four months for them to approve the 504.

NARR: And it changed their life for the better.

Zoe: I’m so grateful because I would not have gotten through my junior year without it. But I’m now realizing, like, so many people don’t have access to therapy or a psychiatrist or a parent that will stand up for them. And even with that, it was almost impossible for me to get one. I feel very lucky.

Ava: Zoe is just one of many students who have had to endure a long process to get the accommodations they deserve. Every year, thousands of families face delays, according to city statistics. Families might feel like they’re fighting an uphill battle when navigating the notoriously complex special education system. And students often don’t get all the services they’re entitled to. Nearly a third of students who were referred and qualified for special education for the first time last year waited more than 2 months for an IEP meeting to be held.

Ava: And, even when students get IEPs or 504s, and are granted accomodations–they’re not always enforced. For example, when it comes to testing, students I spoke to said teachers sometimes forget, or resist giving students the extra time they need. The teacher also may not have received a student’s IEP or 504 documents outlining the accommodations a student is entitled to. Zoe explains…

Zoe: I had an experience in my forensics class last year where my teacher was basically like, “Oh, I don’t know where the school sent your 504 stuff. I haven’t gotten it, so you can’t use your extra time.” What? Like I have extra time. And so I have had experiences where, like, teachers discount extra time or like, are ignorant to it in some way. They’re like, “Well, I didn’t know that.”

Ava: Zoe isn’t the only one struggling from not being able to use their accommodations. Becca Sidi has experienced similar setbacks. She’s a senior at Beacon who’s had an IEP for ADHD since she was in elementary school. Her IEP entitles her to double time on exams, the ability to take tests in a separate room, tutoring, extensions on assignments, and more. One time, Becca said a teacher accused her and other students of cheating because of their extra time.

Becca: After a midterm, my teacher had gathered everyone who– who was an IEP student, and then he goes on to say something about how we got suspiciously higher test scores. I didn’t cheat, but in that moment, I just felt, like, scared.

Ava: Another one of Becca’s teachers told students that they would need to use all of their extra time in one sitting, meaning they would have to miss part of their next class.

Becca: I was missing other instruction. But at the same time, my teacher was also blaming me for missing other instruction. She told us, “Don’t you guys have class? Like, this is ridiculous.” And what everyone wanted to say to her in that moment was, “Well, I mean, this is your policy, and we’re not necessarily happy that we’re missing instruction either.”

Ava: For Becca, It’s not just teachers who don’t always understand the necessity of accommodations. Some students don’t either.

BECCA: I finished taking a calculus test once, and I think I overheard some people in the hallway talking about how someone who with an IEP, who was still taking the test. And then they were saying something like, “Oh, wow. Why does this person get extra time, this isn’t fair, like.” I feel like there are just some things that some people don’t understand or refuse to understand. I cannot stress this enough, like people have IEPs, not to have a leg up on everyone else, but to stay at the same level as everyone else.

Ava: While this may sound shocking to you listeners, this is daily life for me and so many of us among the nearly 20% of students who have IEPs across the city.

I reached out to the city’s Department of Education, as well as Beacon’s principal, for comment on the incidents students shared with me. Department officials emphasized that they regularly train staff to make sure students get the support they’re entitled to — including extra time. And 504 coordinators are required to complete training every year. Education Department spokesperson Nicole Brownstein wrote the following in a statement: “We are steadfast in our commitment to ensuring all students receive their entitled accommodations in accordance with their IEPs and 504 plans.”

Ava: She added, “When a concern is raised, we work closely with the school support team until the family is satisfied with the resolution.” Johnny Ventura, Beacon’s interim principal, wrote in an email that “students who believe they’re not getting the right accommodations should report it to him so the school can investigate.” So why is this happening? Why might it take so long for students to get IEPs and 504s? And why are they sometimes not being enforced? To answer this I spoke to Dr. Ben Lovett, an associate professor of psychology and education at the Teachers College of Columbia University. We first discussed the benefits of extra time.

Ben: The primary reason that we give extra time or other accommodations is so that the student can get a fair score on the test. So if someone is not able to read quickly enough, then they wouldn’t be able to read the items on the test in time, and they wouldn’t be able to show the knowledge that they have.

Ava: So if there are benefits, why would some people be opposed to granting students extra time?

Ben: I’m not sure there are many people who are opposed entirely. I think there are some folks who think we need to be more careful about granting extra time. So we know that on standardized tests, having extra time can inflate scores artificially. And by that I mean they can actually suggest that someone has higher skills than they do. And that’s part of the reason that we want to make sure that we’re using decisions very carefully about who gets extra time, that it be done equitably, and that it be based on someone’s actual needs.

Ava: I ask Dr. Lovett about the process of granting students accommodations. He says there’s typically a school team that reviews a student’s diagnostic assessments. This can include 504 and IEP plans or evaluations done by psychologists and special educators. They also review other relevant student data, like their academic performance.

Ben: Things like the student’s current performance without accommodations to see whether or not the student is able to perform at a certain level without having extra time. Another piece of relevant data would be information from diagnostic tests where we look, for instance, at how fast someone is when they’re reading or writing, and we’re able to compare them to other kids of the same age.

Ava: What would you say the shortcomings of this process are?

Ben: I think the process, in general, is a good one. I think some school districts need more resources to follow the process, so there may not be a sufficient number of school psychologists or special education administrators to make sure that there’s not a long wait before things happen. So, for instance, the federal law requires that generally, within 60 days of a formal request for an evaluation, that the evaluation be done or contested. And so some districts aren’t able to meet those goals if they have insufficient resources in terms of staffing and things like that.

Ava: Because of the lack of resources, families who pay for private evaluations have a big advantage. These evaluations — which typically cost more than $6,000 — can lead to a two-tiered system. Those who can afford outside evaluations and understand how to navigate the system are more likely to get their children’s needs met, while the needs of many other students go unaddressed.

Ava: So, what’s the best way to ensure that extra time can be equitably enforced throughout New York City?

Ben: I would say having official criteria, having a decision tree or a flowchart of data where you ensure that folks who are getting extended time meet certain criteria and that you’re not just in, for instance, letting someone’s social advantage allow for accommodations would be important. Also, having that sort of database process protects students who may lack certain types of access and resources to be able to persuade or pressure a school for extra time to make sure that they can point to that process and say, I do have the data, I do have the evidence that I need this.

Ava: So Dr. Lovett believes we have a good system in place. But the most effective way to ensure students with disabilities get the accommodations they need, is to make sure schools have the resources necessary to accommodate them. It’s time to reallocate more resources into special education across New York City schools. Everyone deserves a quality education. No one’s disability should hold them back.

Bernie: Once again, that was our P.S. Weekly Reporter, Ava Striker-Robbins. We’ll be back, after a short break.

AD: Hey listeners! We hope you’re enjoying this episode of PS Weekly. We’ve got an assignment for you-- follow us on Instagram @bell.voices. And, we want to hear from you! Reach out to P.S. Weekly at the email address: psweekly@chalkbeat.org with comments, questions, and suggestions.

Bernie: Welcome back to P.S. Weekly. We’ve been hearing about how difficult it is to get specialized learning accommodations. Our producer Santana Roach roamed the school halls to chat with a few more students with IEPs and 504s.

Santana: I had the privilege of speaking with several students and a teacher from Frederick Douglass Academy 2 and Stuyvesant High School.

Santana: What do people often misunderstand about students with IEPs?

Jack: They assume that we’re all what’s the word “special.”

Kaiya: They think that we’re like different. They look down on us as if there’s, like, something wrong with us or, like, we’re disgusting. Not everyone wants to be treated like differently, no matter of your race or gender or even if you have autism.

Mr. Wheeler: To be brutally honest, I very much felt that the fact that I had an IEP meant that there was something wrong with me.

Santana: Who are some people advocating for students with IEPs?

Hana: There are lots of counselors who advocate for me and for other things that I might need.

Kaiya: Oh, the psychologist.

Jack: My guidance counselor.

Keimar: My mom and myself.

Santana: How has your IEP helped you?

Jack: I’ve been able to pass my classes because I have an IEP.

Giandre: I get extra time on the tests. It’s a great experience cause I don’t gotta rush. I can just take my time on test.

Jack: When I have an IEP, I can prove that I’m smart.

Santana: What would you like to share with our listeners?

Kaiya: Don’t judge a book by its cover because you never know what you might see inside the book.

Mr. Wheeler: The way to make sure that students with IEPs are treated the way they deserve is to make sure that the paperwork never takes precedence over the person.

Santana: Thank you to Jack Blake, Kaiya Baker, Hana Debrah, Giandre Sorey, Keimar Miller, and Mr. Isaac Wheeler for speaking with PS Weekly.

Bernie: Thank you Santana. Well, there you are, guys…that’s it for our third episode! Don’t forget to go to chalkbeat.org/newsletters– or click the link in our show notes –to sign up for the Chalkbeat New York morning newsletter. It’s the best way to stay informed on local schools coverage Monday through Friday. And drop us a review! Or shoot an email to PSWeekly@chalkbeat.org. Tell us what you learned today or what you’re still wondering. We just might read your comment on a future episode.

Bernie: And P.S., we’re back next week with an episode about high school seniors making decisions about the future.

Alex: Someway halfway through, you kinda have this realization that “what if this is all for nothing? Like, what if I’m here writing these essays, and nothing comes out of it?”

Bernie: Until then… class dismissed!

CREDITS:

Bernie: PS Weekly is a collaboration between The Bell and Chalkbeat, made possible by generous support from The Pinkerton Foundation, The Summerfield Foundation, FJC, and Hindenburg Systems.

This episode was hosted by me, Bernie Carmona.

Producers for this episode were: Ava Striker Robbins, Santana Roach, and Dorothy Ha, with reporting help from Chalkbeat reporters Alex Zimmerman and Mike Elsen-Rooney.

Our marketing lead this week was Jose Santana. Our executive producer for the show is JoAnn DeLuna. Executive editors are Amy Zimmer and Taylor McGraw.

Additional production and reporting support was provided by Sabrina DuQuesnay, Mira Gordon, and our friends at Chalkbeat. Special thanks to our interns Miriam Galicia and Makenna Turner. And thanks, as well, to our amazing team of volunteer mentors.

Music from Blue Dot Sessions.

And the jingle you heard at the beginning of this episode was created by the one and only: Erica Huang.

Thanks for tuning in! See you next time!