Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to keep up with NYC’s public schools.

In late 2022, New York City’s Public Schools Athletic League made a bold promise: By the following spring, every public high school student would have access to all 25 sports the league offers.

To reach that goal, officials proposed expanding a program called “individual access” that allows students without a particular sports team at their school to try out for that team at a nearby campus.

The expansion was a game-changer for schools like the Urban Assembly Bronx Academy of Letters that don’t have enough students to reliably field a wide variety of sports teams, said David Garcia-Rosen, the dean and athletic director of the 470-student school.

“In spring of 2023, every single kid in New York City, no matter where they went to school, had the opportunity to play whatever sport they wanted to play,” Garcia-Rosen said.

But Garcia-Rosen, a veteran advocate for sports equity in city schools, is worried that the Education Department is quietly laying the groundwork to scale back the initiative. And he’s gearing up for a fight. The dispute over individual access is the latest chapter in a long-running fight over sports equity in New York City schools.

Despite previously pledging to open individual access to “all” students, the PSAL updated its website in February to describe the individual access program as a “pilot” for students at schools with fewer than six teams in “targeted districts.”

That language is in line with the stipulations in a 2022 legal settlement about sports equity. But it excludes the vast majority of city students.

An Education Department spokesperson said the PSAL is now prioritizing individual access requests from kids in schools with the least access to sports. The spokesperson said roughly 1,500 students participated in individual access this year, but didn’t share how many kids participated last year.

Officials concluded that guaranteeing individual access beyond what was required by the legal settlement “moved us away” from the goal of increasing sports access for entire schools, the spokesperson said.

To better achieve that goal, officials have expanded the number of new teams by 222 over the last three years and created 20 shared-access programs between schools.

“There has been no scaling back of our commitment to providing equitable access to PSAL sports, and students and families have told us that they want access to teams at or close to their home school,” said spokesperson Nathaniel Styer.

But Garcia-Rosen said that approach demonstrates a “complete lack of understanding of how to solve the problem,” because equity isn’t achieved by simply expanding the number of teams. He noted that small schools often can’t sustain the teams because of their low student numbers.

Garcia-Rosen filed a complaint Wednesday with the U.S. Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights alleging that curtailing individual access disproportionately harms Black and Hispanic students.

A long-running fight for sports equity

Black and Hispanic students are disproportionately clustered in small schools like Bronx Letters, meaning they’ve historically had far less access on average to a wide variety of sports.

Just 38% of Black and Hispanic students go to a school with 20 or more teams, compared to 61% of students who are white, Asian, multiracial, or belong to other groups, according to research compiled by Garcia-Rosen.

A major milestone came in 2022, when the city agreed in a legal settlement to add 200 new teams in future years and expand a “shared access” program that allowed small schools in the same geographic area to combine sports programs.

The city also committed to offering individual access to students in schools with under six teams and couldn’t participate in shared sports programs because of their location.

But Garcia-Rosen argues that those steps alone won’t erase the equity issues.

That’s why universal individual access — what Garcia-Rosen calls the “holy grail of equity” — is so transformative.

“It’s really simple, and it’s done all over the country,” he said. “If you go to a school that doesn’t have the team you want to play, you could try out [at] another school in the district.”

Students, educators report positive results

Students at Bronx Letters, a public school for students in grades 6-12, are accustomed to not knowing year to year whether there will be enough interested students to field a given team.

This school year, Bronx Letters didn’t have enough kids for a girls basketball team.

But 15-year-old sophomore Jayla Jerez, an avid player, was able to join the team at South Bronx Prep, just a five-minute walk from her school, through the individual access program.

“It was just a great experience,” she said. “I felt good to be able to play and get more used to being on the court and being more open to socializing with people.”

Jerez values basketball and wants to keep playing. If she can’t participate through individual access, she might have to consider transferring schools, she said — an option she is not relishing.

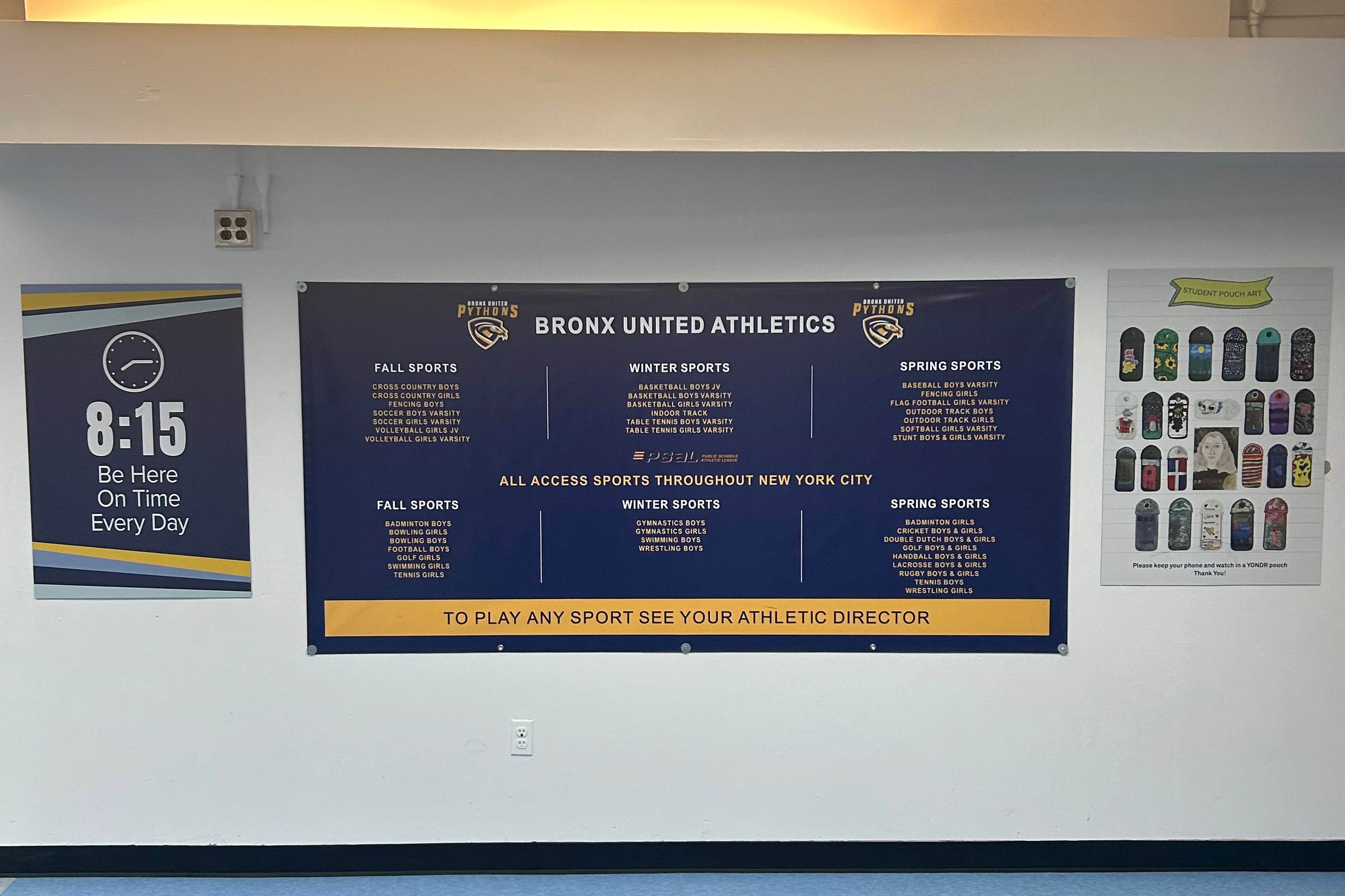

Losing a guarantee to individual access for all students could also change how schools communicate with families about sports options, he said. Last year, Garcia-Rosen could promise prospective families that their kid would have access to every PSAL sport at Bronx Letters. He even printed a banner advertising that option.

Without that same assurance for next year, he said, “when a family comes to pick a high school, I can’t guarantee them that they come to this school and have access to every sport.”

Setting up the individual access program requires clearing some administrative and logistical hurdles, but administrators have largely reported positive results, Garcia-Rosen found.

He said he reached out to athletic directors and principals across the city, and 49 of the 51 who responded said they supported maintaining universal individual access.

One athletic director from Manhattan, who asked to speak on the condition of anonymity, told him “it has definitely taken a lot of work to get this program off the ground but it is working and students are playing. It will only get better as we invest in it more!”

Michael Elsen-Rooney is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Michael at melsen-rooney@chalkbeat.org.