This story is part of the P.S. Weekly podcast, a collaboration between Chalkbeat and The Bell. To hear the full audio version of this story, listen to our most recent episode.

When fourth grader Elsa Hammerman’s favorite dish disappeared earlier this spring from her school’s lunch menu — the result of budget cuts — she dashed off a letter to the head of New York City’s school food office.

Her plea, adorned with 13 hand-drawn chicken drumsticks, was polite but direct: Bring back the roasted chicken to P.S./I.S. 187 in Washington Heights. It didn’t take long for her advocacy to pay off. Within a few weeks, the dish reappeared in her school’s cafeteria.

“I was super happy, and I was like bouncing off of my friend’s shoulders, and she was like, ‘calm down, calm down,’” Elsa recalled. “Everyone was super excited to see that it was back.”

Elsa wasn’t the only student to complain about the cuts. Schools Chancellor David Banks pointed to the student outcry as a major reason officials ultimately restored many of the menu items after a $60 million cut forced the city to remove some of the most popular food from cafeterias. But Elsa’s letter also won her school a chance to weigh in on future dishes that could appear in hundreds of school cafeterias across the city.

Chris Tricarico, the senior executive director of food and nutrition services who received Elsa’s letter, invited her class to the Education Department’s school food test kitchen. About 1,500 to 2,000 students across the city visit every year to offer feedback on new menu items the city is considering for school cafeterias — and the visits are so popular that there’s a waitlist for principals to sign up.

“We were able to fit her in,” Tricarico said, “so her whole class could see that their voice, their concern, and their advocacy for school food was really important.”

Last month, Elsa and about two dozen of her fourth-grade classmates trekked to the department’s test kitchen in Long Island City, Queens, to try out four menu contenders: an egg and cheese sandwich, a cheesy pasta dish called manicotti, hummus, and a barbecue chicken slider.

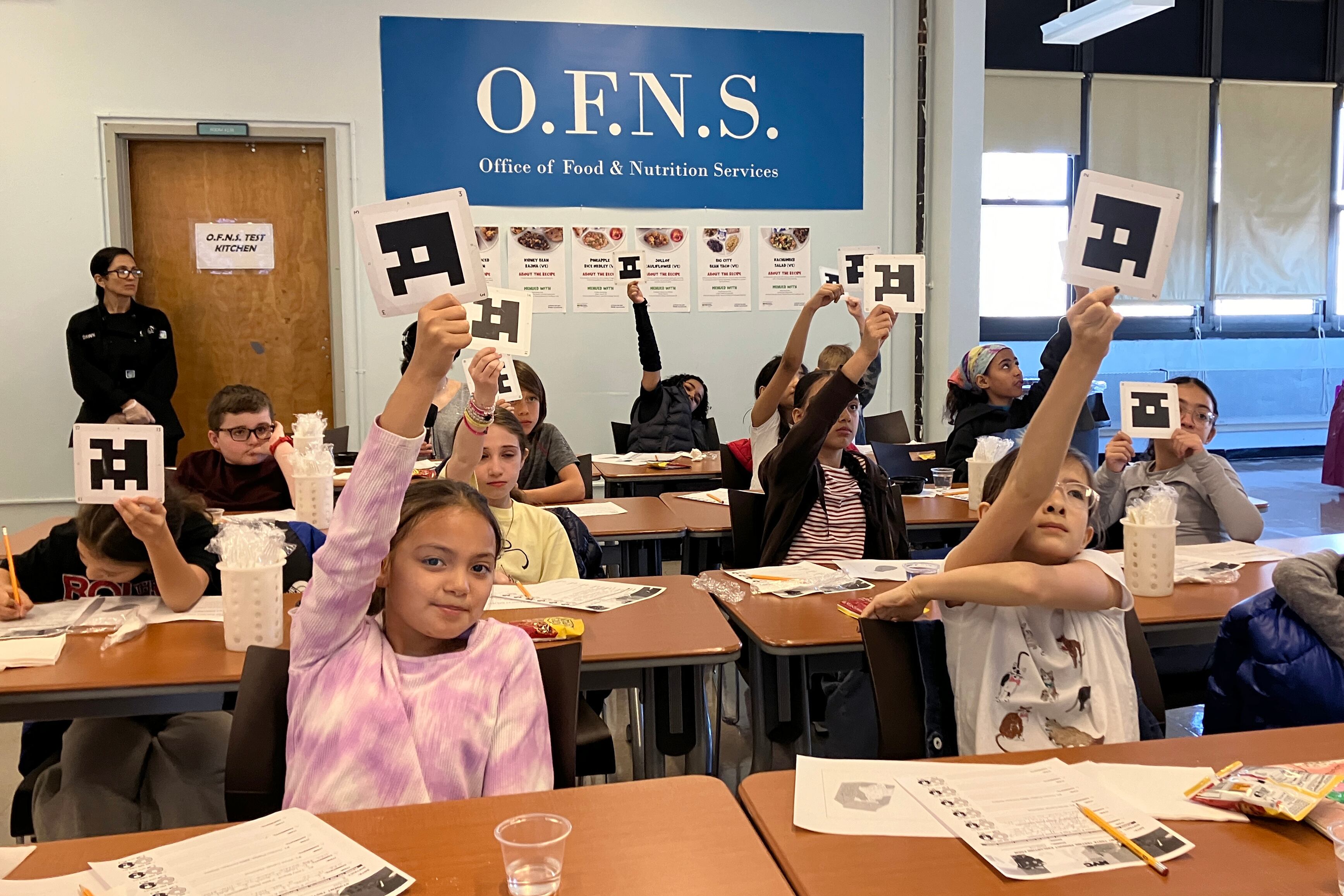

The students, assembled in a mock classroom inside the warehouse-style building, sat at rows of desks while sampling each item. They tried the dishes without talking so they could develop opinions without influencing each other. Using a card called a plicker, which looks like a fancy barcode, they signaled their overall rating. If they held the card right side up, it meant they approved of what they just ate.

Roughly 200 students typically try each food item and about 75% have to approve before they’re added to school cafeterias.

Chantal Hewlett, the taste testing supervisor, stood at the front of the room to scan all the codes at once with her phone, which generated an instant tally of how many students liked the dish. Afterward, students shared more detailed feedback on worksheets and verbally during a group discussion.

“If you don’t like something, it’s okay, let us know now so we can fix it,” Hewlett explained to the fourth graders. “We take your comments and we share them with the company.”

Elsa and her classmates weren’t afraid to share their frank opinions of the food. The first dish, which looked like a dinner roll stuffed with eggs and melted cheese, was largely a winner.

“I really like the meal,” one student chimed in. “Usually eggs give me headaches, so the way that the egg was cooked, [it] didn’t like give me a headache.”

Eighteen of the 22 student testers gave the eggs a favorable rating.

The manicotti — tubes of pasta stuffed with ricotta cheese and topped with tomato sauce and a dusting of parmesan — was a different story. Eleven of the 21 students who tasted it shifted their barcodes sideways to give it a thumbs down.

“I didn’t like it, because there’s too much cheese, and it got stuck to the plate when I tried to eat it,” one student said. The ricotta cheese was a big drawback for many of the student critics.

School food officials emphasized that even the harshest student criticism is crucial. After all, if food that students don’t like ends up on cafeteria trays, they’ll toss it in the garbage. And student feedback is even more crucial as city officials experiment with more culturally diverse menu items and a wide array of vegetarian options on “meatless Mondays” and “plant-powered Fridays.”

As the test kitchen visit wound down, the fourth graders reflected on their experience. One student, Athena, said she typically relies on food sent from home.

“Now I think school lunch is better,” she said.

Another classmate, Benson, said Elsa’s letter might inspire him to push for his own favorite dishes.

“I really appreciate the letter that she made. And maybe I’ll make a letter, too,” Benson said.

What would it say?

“To bring fried chicken to the menu,” Benson replied.

To hear the full story of Elsa’s visit to the school food test kitchen, listen to the latest episode of P.S. Weekly.

Ava Stryker-Robbins is a senior at Beacon High School in Manhattan and an intern at The Bell.

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.