Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to keep up with NYC’s public schools.

New York City education officials are weighing a plan to give students from Manhattan admissions priority at several of the borough’s most competitive high schools, according to four people familiar with the plan.

The list and number of schools that would offer the admissions bump is not finalized, but the campuses under consideration include Millennium High School, Beacon High School, Bard Early College High School, and Eleanor Roosevelt High School, according to one of the sources. Baruch College Campus High School, NYC Lab School for Collaborative Studies, and Clinton High School could also offer the geographic priority, the person said.

The geographic priority would apply to students across the entire borough of Manhattan rather than just those in District 2 — the zone spanning most of lower and midtown Manhattan and the Upper East Side. Most of the schools that would be affected are in District 2.

A Manhattan borough preference would mark a major change in admissions policy at some of the city’s most in-demand schools and reverberate across the NYC education system. It would also be the latest chapter in a years-long debate over whether and how schools should consider where students live in admissions.

Several of the schools that could offer the new borough priority had previously given preference to District 2 students until former Mayor Bill de Blasio scrapped that policy in 2020. Other schools being considered, including Beacon and Bard Early College, have not previously offered any geographic priority.

It’s not yet clear how many seats at each of the schools would be held for Manhattan students. Education officials are hoping to finalize a plan by the end of the month. The policy would go into effect for the upcoming admissions cycle for students who start high school in the fall of 2025, according to the sources.

Education Department spokesperson Nathaniel Styer declined to comment on the specifics of the plan. “Every year we engage parents around improving enrollment for all students and families in our schools. We will have more to say about updated policies soon,” Styer said.

In a forum with Manhattan parents Thursday night, schools Chancellor David Banks expressed support for the general idea of a Manhattan priority and sympathy for the borough’s parents.

“If you are a mom or dad and you have a child in District 2, I can only imagine how heartbreaking that is that you didn’t even have an opportunity to get your child into one of the District 2 middle schools or high schools as you’re watching kids coming from all around the city coming to the school and you live across the street,” he said. “I don’t think that is fair, and so I’m looking at a wide range of ways to try to find a common ground for everyone.”

Admissions proposal likely to draw mixed parent reactions

Giving preference to students across Manhattan instead of just District 2 — as Banks had previously hinted he might do — makes the priority available to a wider swath of kids who are more representative of the city.

Across Manhattan, 56% of K-8 students are Black or Latino, and 59% come from low-income families, according to state data. In District 2, 26% of K-8 students are Black or Latino and 35% come from low-income families.

Education Department officials forecast that socioeconomic demographics wouldn’t shift significantly in schools if they adopt the Manhattan preference, according to people familiar with the plans.

Many of the schools under consideration set aside a portion of their seats for students from low-income backgrounds. Those policies would remain in place alongside the geographic preference, the sources said.

Elissa Stein, a high school admissions consultant who works with many Manhattan families through her company HS 411, said “giving every family in Manhattan an opportunity to go to these schools is terrific,” and it’s “a really smart move to include more families” beyond just District 2.

Banks said in the Thursday forum he considered it a matter of fairness to give Manhattan students the kind of geographic priority that selective schools in other boroughs offer.

As of 2021, 235 of the city’s roughly 400 high schools offered a borough preference (Education Department officials didn’t provide an updated number). Another 30 schools, none of which are in Manhattan, prioritize students who live in the surrounding geographic zone, according to the city’s high school directory.

“We’ve got some enrollment policies in place in other boroughs that ensure that folks who are in those boroughs get some level of priority,” Banks said. “We don’t do that as much in Manhattan.”

But Maurice Frumkin, who’s also an admissions consultant and president of NYC Admissions Solutions, said he’s concerned the plan is moving forward without sufficient input from families outside of Manhattan. Such families apply in large numbers to Manhattan’s selective schools because of their strong reputation and their accessibility, and they could have strong negative reactions to the plan being weighed by officials.

“To think that they would be excluded potentially from many schools is really going to be a shock to their system,” said Frumkin, who previously worked in the Education Department’s office of enrollment.

Critics of the plan contend that instituting geographic priority in Manhattan’s most popular schools is more disruptive than adding geographic preferences in other boroughs, because Manhattan is a hub for kids from across the city in a way other boroughs aren’t.

More than half of the students currently enrolled in Manhattan high schools live in other boroughs, including nearly a quarter who commute from the Bronx, according to city figures. Fewer than 10% of students who attend high school in each of the other four boroughs commute across borough lines.

Manhattan also has a disproportionate share of the city’s most sought-after schools. There are at least eight schools in Manhattan that receive at least 10 times as many applications as seats, according to city data. No other borough has more than two.

Debate over geography and school admissions spans years

Some school integration advocates have pushed for years to eliminate all geographic weights in admissions, arguing that they exacerbate racial and socioeconomic segregation.

In December 2020, when he eliminated the District 2 priority, de Blasio seemed to be headed in that direction, promising to get rid of all “geographic screens.” But he reversed course in 2021 after significant pushback from families, and ended up eliminating only the district priority, but keeping the priorities for zones and boroughs.

Many of the city’s largest comprehensive high schools, like Francis Lewis High School in Queens and James Madison High School in Brooklyn, give out almost all their seats to students in their zone or borough. Other smaller competitive schools, like Millennium Brooklyn and the Academy of American Studies in Queens, admitted only students from their boroughs last year.

The city has recently opened several new high schools outside of Manhattan, including Bard Early College programs in the Bronx and Brooklyn. Both new Bard programs are located in lower-income neighborhoods and prioritize students from surrounding districts.

Manhattan has no zoned high schools. The high school directory doesn’t allow a search by borough priority. But a recent tally from the Citywide Council on High Schools, a group of parent representatives, found 19 schools in Manhattan that currently offer borough priority. Those schools tend to be less competitive.

Yael Denbo, a parent and member of the Community Education Council in District 3, which covers the Upper West Side and parts of Harlem, said she’s been hearing from lots of families who “are concerned, rightly so, about their children commuting out of borough for maybe an hour or two per trip.”

Students in District 2 were admitted at the lowest rate in the city to one of their top three high school choices, with 55% getting in last fall, according to Education Department figures. District 3 had the fourth-lowest rate in the city at 63%.

Only 42% and 44% of high school students who live in Districts 2 and 3, respectively, attend a high school in their home district, the second- and third-lowest rates in the city, according to city data.

Critics of geographic priority point out there are plenty of open seats in Manhattan high schools — more than 18,000 last year, according to Education Department figures — but they’re just not at the schools that generate the most interest.

Students from other NYC boroughs brace for impact

The impacts of adopting Manhattan priority at some of the borough’s most popular schools would be widespread.

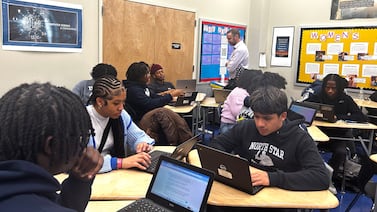

At P.S. 218 in the South Bronx, where more than 90% of students are Latino and come from low-income families, a large number of students apply annually to some of Manhattan’s most competitive high schools because the families know their reputations and they are easy to get to, said Nicole Jennings, who runs a high school admissions support program through the non-profit WHEDco based at P.S. 218.

“We do have a decent number of students who go to those schools, maybe five to six a year” from P.S. 218, Jennings said. “And if this change goes into effect, I’m imagining it will just erase that.”

Jennings said she appreciates the city’s efforts to open more academically rigorous schools in the Bronx, like Bard Early College Bronx. But she said many of the families she works with are wary of sending their kids there because of neighborhood safety concerns.

“Schools in Manhattan tend to be much more appealing … than ones in the Bronx, sadly,” she said.

Frumkin, the admissions consultant, said his broader concern is that continuing to add more geographic priorities will chip away at the fundamental purpose of the citywide choice system.

“You have this matching process that was pioneered to create this ‘fair and equitable’ citywide choice process,” he said. “And yet you’re overlaying these little intricacies on top of that.”

Michael Elsen-Rooney is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Michael at melsen-rooney@chalkbeat.org.