Top officials in the city and state are still gathering information on how to address cellphones in schools as they consider a possible ban.

New York Gov. Kathy Hochul on Monday kicked off a statewide listening tour that will include discussions with administrators, educators, and others over the coming months to inform a policy proposal for the state’s schools on smartphone use expected to be unveiled later this year.

At a citywide meeting for principals on Monday, New York City schools Chancellor David Banks told school leaders that the Education Department was still doing its research — signaling an apparent pause after Banks had told reporters that a big announcement on a citywide school cellphone policy was imminent.

Principals were asked at the start of the meeting to complete a survey on cellphones, asking them if they already collect phones and whether they planned to implement a cellphone policy for the upcoming school year, school leaders told Chalkbeat.

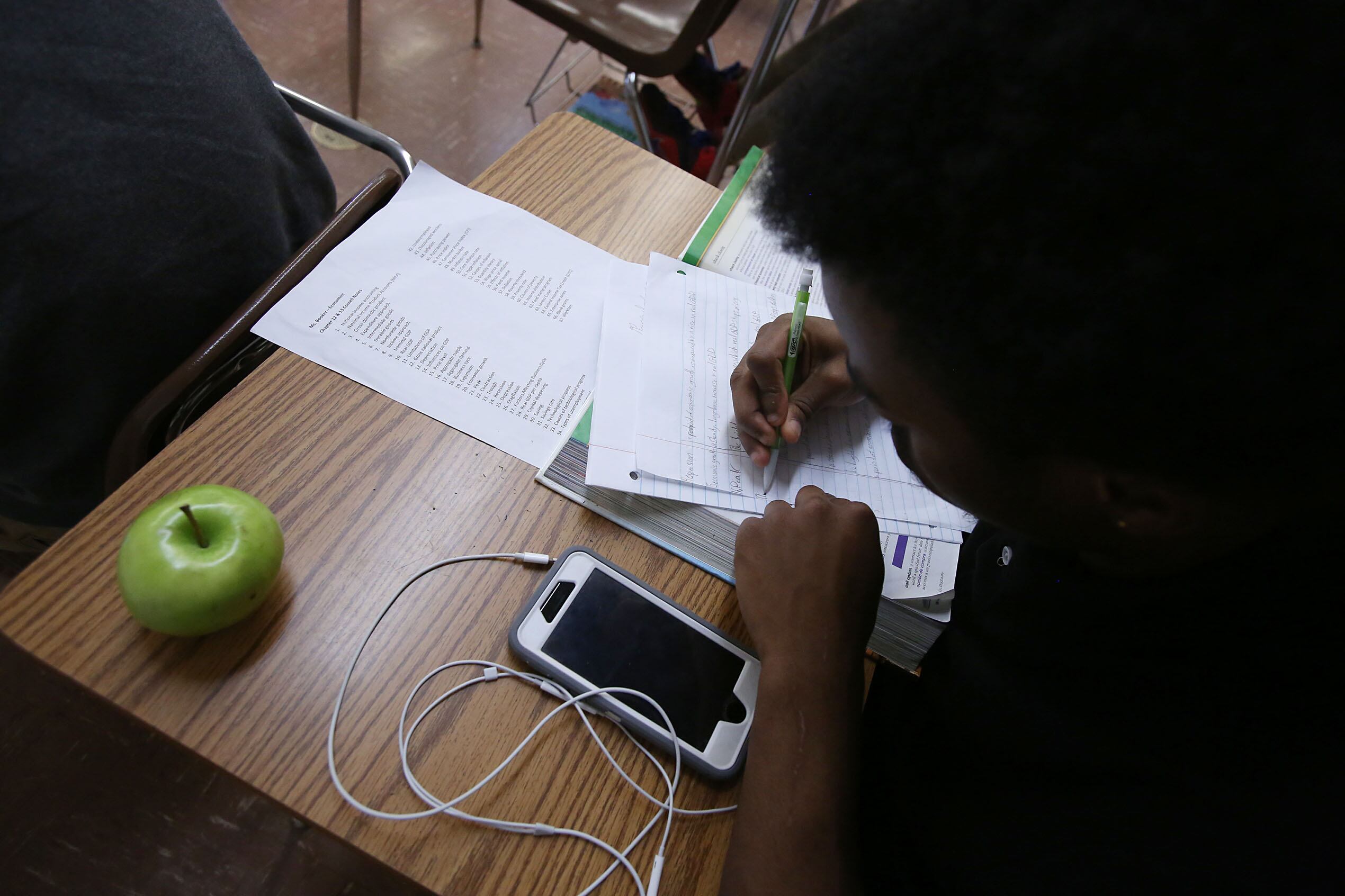

A Pew Research poll from June found that 72% of high school teachers nationwide said cellphone-related distractions were a major problem in their classroom. And a survey conducted by Chalkbeat echoed these findings, with teachers saying they feel ignored and have to dedicate more and more time to policing phone use.

Many educators and families are concerned about harmful mental health effects. “The Anxious Generation,” a new book by Jonathan Haidt, a New York University Stern School of Business social psychologist and New York City public school parent, builds a strong case for phone-free schools. Haidt also urges parents to withhold smartphones from students before high school and to prohibit the use of social media before age 16.

On the flip side, some educators and parents have said that schools should teach kids to use their phones responsibly instead of banning the devices. Parents are often prime offenders in calling or texting their children during the school day, teachers and parents told Chalkbeat. One parent told Chalkbeat that there were many times when her daughter, a recent high school graduate, had to “pounce” on a call to deal with college or scholarship applications.

Former Mayor Bill de Blasio lifted the school system’s cellphone ban in 2015, concerned about inequities for students who were paying local businesses to store their phones before they entered school. The Education Department then allowed schools to come up with their own policies. As a result, there’s a patchwork of policies at schools across the five boroughs.

Some schools may have policies on paper barring phones, but in practice, teachers are left figuring out how to enforce those rules. Others collect and store phones during school hours. And many have their students carry around Yondr pouches, cloth cases for phones that are locked from morning to dismissal.

A third of New York City high schools use Yondr pouches to collect phones, twice as many as last year, officials from the 10-year-old pouch company told Chalkbeat. The pouches cost about $25 to $30 per student, with pricing varying depending on school size, a company spokesperson said. Yondr said it’s expecting “significant growth” in pouch use in New York City and beyond.

Chanan Kessler, a special education teacher at Bronx Health Sciences High School, which shares a campus with several other schools, said his school was the only one in the building this past school year that implemented Yondr pouches, and by the end of the year, many students had figured out workarounds. He and his co-teacher did an experiment in one classroom to gauge compliance: They asked students to take out their phones to do an assignment and offered computers to anyone who didn’t have a phone on them.

About 70% had their phones accessible, Kessler said.

Students would hand their phones to students in the other schools and then collect them later, use “dummy” phones for the pouch, or just break into the pouches. Some kids, he said, figured out ways to turn their phones on and listen to music even when their phones were in pouches. And what about students with smart watches, he wondered. Seniors were less compliant than freshmen, he said.

Moreover, teachers did not enforce the policy of confiscating phones. In fact, Kessler said teachers were instructed not to touch students’ phones. As the city and state both work on crafting cellphone policies, Kessler is worried that enforcement will still fall on teachers — and that it won’t be easy.

“How do you enforce it, when students are really feeling that the phone is an extension of their being?” he asked. “When there’s mass resistance, teachers give up.”

But even if only half the students complied with the pouches, he said, it was still better than no policy.

“It sent the message that you’re not allowed to have your phone,” Kessler said.

Amy Zimmer is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat New York. Contact Amy at azimmer@chalkbeat.org.