Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to keep up with NYC’s public schools.

Sweeping changes to literacy instruction are underway in New York City, with all elementary schools for the first time using one of three mandated curriculums this September.

By requiring instruction in line with long-standing research about how children learn to read, known as the science of reading, the city is hoping to boost its literacy rates. Just under half of students in grades 3-8 are considered proficient in English, according to state exams.

After Chancellor David Banks took the helm of the nation’s school district more than two years ago, he said the city’s approach to reading instruction “has not worked” and has since made the curriculum overhaul his signature initiative. His other policies, he told Chalkbeat, pale in comparison to fixing reading instruction.

“None of that will even matter if kids can’t read,” he said.

But what do the new curriculums look like? How do caregivers know if they’re working? And what should you do if your child continues to struggle?

Here are answers to some common questions caregivers may have about the changes, based on interviews with reading experts and educators.

How were schools teaching reading before?

Stretching back decades, the Education Department embraced a program developed by Teachers College professor Lucy Calkins, which viewed reading as a natural process that could be unlocked by exposing students to literature. Teachers delivered mini-lessons on a specific skill then encouraged students to read books at their individual levels to practice what they learned.

But most reading experts say the approach did not include enough emphasis on teaching children the relationships between letters and sounds, known as phonics, leaving behind a substantial share of students who would benefit from more explicit sound-it-out lessons.

Calkins’ curriculum also deployed some dubious methods, such as encouraging students to use pictures to guess at a word’s meaning rather than relying on the letters themselves. Though she has since added a greater emphasis on phonics, the city’s public schools will no longer be allowed to use her program.

What is the philosophy behind the literacy shift?

All schools are now required to deliver regular phonics instruction that explicitly teaches the relationship between sounds and letters. Those lessons, which are prioritized in grades K-2, typically run about 30 minutes a day.

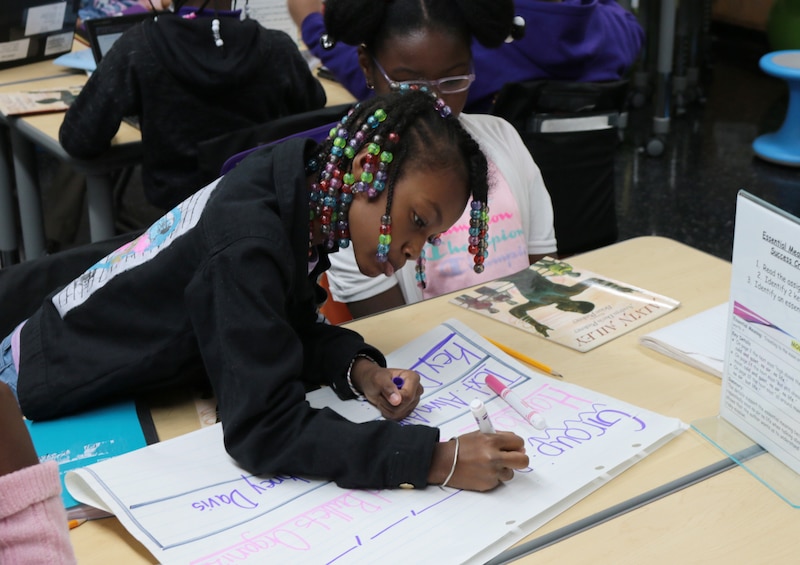

In addition to those lessons, schools must also use one of three approved reading programs that are designed to help build vocabulary and comprehension by exposing students to social studies and science topics alongside works of literature and poetry. Research suggests that students are more likely to understand what they’re reading if they’re already familiar with the underlying topic. The new curriculums are designed to build students’ background knowledge across a range of domains.

“You should, as a parent, ask your kid about the books that they’re reading and be prepared to hear an earful from your child about how they read about Jacques Cousteau and the discovery of the giant squid — or to know a whole lot about pollinators,” said Kristen McQuillan, who consults with districts on literacy efforts and is affiliated with the Knowledge Matters Campaign, which raises awareness about the role of background knowledge in reading comprehension. Students should be bringing home writing about those books, too, she added.

Under the old curriculums, students often picked books that interested them from the classroom library that were targeted at their individual reading levels. Although the city is moving away from that leveling system — and instead having kids spend more time reading common books as a class — the practice may continue to some degree. Teachers will still have access to those leveled books, though they have been asked to organize them by topic or genre. Into Reading, the most widespread curriculum under the new mandate, also offers its own set of leveled books that schools can use.

What are the three new curriculums and which one is my school using?

The curriculum rollout began during the 2023-24 school year with 15 of the city’s 32 local school districts required to use one of the three reading programs: Into Reading from the company Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; Wit and Wisdom from Great Minds; and EL Education from Imagine Learning.

Beginning this September, all elementary schools must use one of those three programs, with local superintendents in charge of making curriculum decisions for all schools in their district. Here’s what each district is using:

What do the three new reading curriculums look like?

Into Reading from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Into Reading is by far the most popular choice among superintendents. Schools in 22 of New York City’s 32 local districts must use it. The most traditional of the three curriculums, Into Reading is organized as an anthology-style textbook packed with passages specifically designed to help teach reading skills, an approach known in education jargon as a “basal reader.” Some caregivers may be familiar with the approach from their own schooling.

Unlike the other two curriculums, Into Reading includes a Spanish-language version. And it covers a lot of ground, with roughly a dozen units in some grade levels that include how plants live and grow, the relationship between sports and teamwork, and how a person’s experiences shape their identity. Some educators say that breadth can be helpful since students may be more likely to encounter subjects that pique their curiosity.

Kate Gutwillig, a veteran New York City educator who has taught all three of the mandated curriculums, recalled one instance where a fifth grader who was reading at a second-grade level was captivated by an Into Reading lesson on Greek mythology.

“He was able to read the Medusa myth and that kid just came to life — he wanted to read aloud and write,” she said. “There’s something good about having a lot of variety.”

Still, Into Reading has earned criticism from some observers, parents, and educators who contend that it is weaker than the other two curriculums because it includes less focus on knowledge building, and relies too heavily on excerpts rather than full books. A New York University report also warned that its materials are not culturally responsive, a claim the company disputes.

Wit & Wisdom from Great Minds

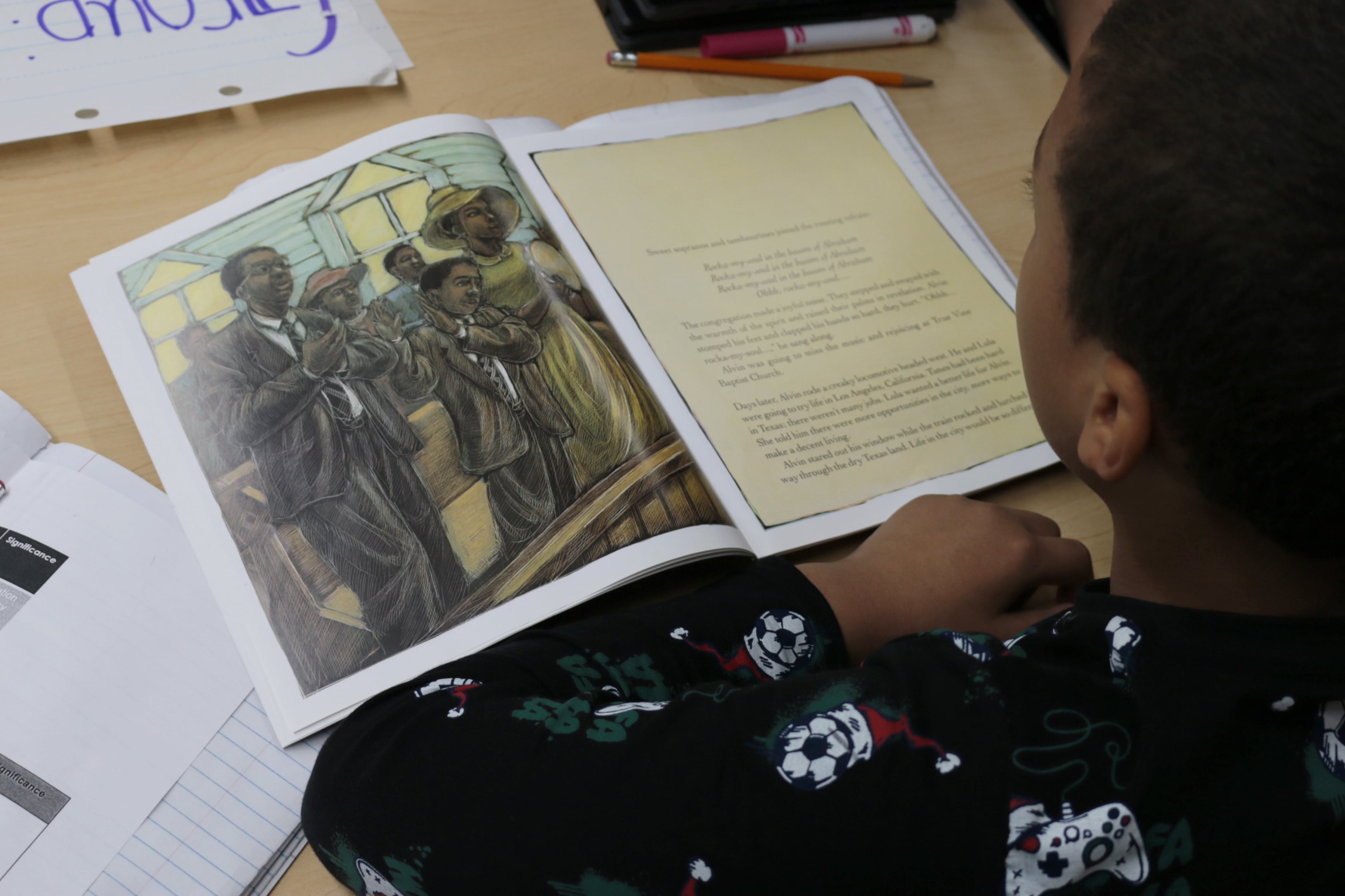

Wit & Wisdom is known for building students’ background knowledge by going deeper into a smaller number of units. The curriculum includes four modules each year — ranging from civil rights heroes to a study of outer space — devoting about 6-8 weeks per topic.

The curriculum exposes students to a mix of fiction and nonfiction texts. It also stands apart for including a “close examination of artwork related to the core topics,” according to the Knowledge Matters Campaign.

“You tend to see a bit more of that literary fiction,” said McQuillan. One fourth grade unit called “the great heart” introduces students to the biology of the heart as muscle that pumps blood while weaving in the figurative meaning of the heart as a representation of emotion and love.

Some educators say adapting to Wit & Wisdom is challenging. The lessons can be lengthy, requiring teachers to figure out how to cut it down to be more manageable. And, as with all three curriculums, students are generally expected to read the same books on their grade level as a class, a challenge for students who don’t yet have strong reading skills.

“I think that’s our biggest struggle,” one teacher who was implementing Wit & Wisdom previously told Chalkbeat. “We’re coming in assuming that the kids have the skills to do this.” (If you’re interested in a deeper look at Wit & Wisdom, Chalkbeat previously featured a Bronx school that was in the process of adopting it.)

EL Education from Imagine Learning

Similar to Wit & Wisdom, EL Education deploys a handful of units each year that students spend several weeks unpacking. Formerly called Expeditionary Learning, the curriculum emphasizes teaching children about the natural world around them and includes lots of opportunities to write. Two kindergarten units focus on trees, for instance, and a significant chunk of second grade is devoted to pollination.

The emphasis on exploring the outside world, McQuillan said, “tends to be a feature of EL that kids get excited about.”

Janina Jarnich, who teaches second grade at P.S. 169 Baychester Academy in the Bronx, previously told Chalkbeat that one of her favorite lessons to teach focuses on paleontology and fossilization.

“By the end of the module, they write a narrative where they are the paleontologist that makes the greatest discovery of their lives,” she said. The lesson “lends itself to lots of hands-on experiences, like making imprints and doing a ‘dinosaur dig.’” She also takes her students on a field trip to the Museum of Natural History.

Some educators noted that the curriculum can be overwhelming — an issue that some teachers said is true of many curriculum packages.

“The weakness is the difficulty of navigating all of the materials,” Jarnich said. “Even after using EL for four years, it can still be tricky to find the end-of-unit assessments and to make sure you have all of the materials necessary for each lesson.”

Are there any exceptions to the new curriculum mandate?

So far, only one school has won an exemption, a K-8 gifted and talented program. However, some other school communities have pushed back against the new curriculum mandate.

Randi Weingarten, head of the American Federation of Teachers, suggested more schools should be offered waivers.

How do I know if the new curriculum is working for my child?

Schools are expected to screen students three times a year to assess their reading skills. Caregivers can find the results of those assessments in their NYC Schools Account, which indicate whether a student is performing at or above grade level or needs more support to be performing at grade level. (These screeners are supposed to replace a previous system that assigned students a reading level from A-Z.)

Multiple experts said teachers are generally also doing more regular assessments on top of that, so it’s a good idea to get in touch with them if you have any concerns.

“The answer is: ask the teachers,” said Susan Neuman, a literacy expert at New York University. They should have a sense of whether a student needs extra help based on a range of assessments beyond the screeners, she added.

What should I do if I’m concerned about my child’s progress?

Experts said caregivers should reach out to their child’s school if they suspect their child is behind in reading or if their screener results suggest they are below grade level.

“A plan needs to be put in place, so parents do need to serve as their child’s advocate,” said Katie Pace Miles, a literacy expert at Brooklyn College who launched a tutoring program to help catch students up. “I would ask about what skills can be reinforced at home, and what materials can be provided to the caregivers.”

She said parents should ask their schools to outline whether they are offering their child extra small-group or one-on-one instruction, how many days a week it’s offered, and how long each session is.

“Parents should not be left in the dark,” Miles said. If a student continues to struggle despite efforts to provide extra help, caregivers may want to ask for more detailed assessments of their child and potentially request a special education evaluation, she said.

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.