Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to keep up with NYC’s public schools.

A $92-million plan to equip all 1,600 New York City schools with cameras, intercoms, and buzzers so they can lock the front doors is more than halfway complete, with officials expecting the safety measures to be finished by June.

Chancellor David Banks has said that the Education Department’s Safer Access door-locking plan is an attempt to “harden” campuses, citing a need to control entry to buildings following violence near city schools as well as school shootings like the 2022 tragedy in Uvalde, Texas.

“We will have every school in New York City completed by the end of this school year,” Banks said at a recent town hall. “It’s a Herculean task, but what that is meant to do is to prevent intruders from getting into our schools, and it’s another layer of safety.”

The issue came up in the vice presidential debate on Tuesday night, when U.S. Sen. J.D. Vance of Ohio, the Republican running mate of former President Donald Trump, said that locking school doors and windows was among the most realistic solutions to gun violence. Tim Walz, the Minnesota governor and Democratic running mate of Vice President Kamala Harris, Walz, called for red flag laws and better background checks.

New York City school leaders, though, are facing mixed reactions about the safety measures. Some local parents support the nationwide trend toward locking or monitoring building access, including those at P.S. 28, a Queens school where an emotionally disturbed person entered the building in 2022 and was wrestled to the ground by the school’s jiu jitsu-trained principal.

But others are skeptical of this method’s effectiveness. A locked front door wouldn’t have prevented the recent school shooting in Georgia, where a 14-year-old student enrolled at the school allegedly shot and killed two students and two teachers, injuring another nine. And some parents question whether the need for safety is strong enough to justify the unwelcome atmosphere of a locked front school door.

“I don’t feel like it should be shut up like prison gates,” said Curtis France, the father of two children at Brooklyn’s P.S. 235, which has not yet been outfitted with the new system. “I don’t feel any more safe with the doors closed.”

Hank Sheinkopf, a spokesperson for Teamsters Local 237, the union representing school safety agents, expressed some doubt that the door-locking project would substantially improve safety.

“We have not been advised of the specifics but maintain that there are no substitutes for more school safety agents and more screening,” he wrote in a statement.

Most elementary schools have the new intercom systems

The city has focused on elementary schools in its first round of upgrades, installing the new system in 78% of them already, officials said.

Installing the tech upgrades got off to a bumpy start last spring, with malfunctioning locks, camera problems, and communications systems snafus, according to the New York Post. The city initially awarded a $43 million contract to Symbrant Technologies, Inc. last year, before the Education Department replaced the company with NTT DATA.

The capital cost of the program increased to at least $92 million from $78 million because additional buildings needed upgrades to accommodate the system or extra functionalities, Education Department officials said.

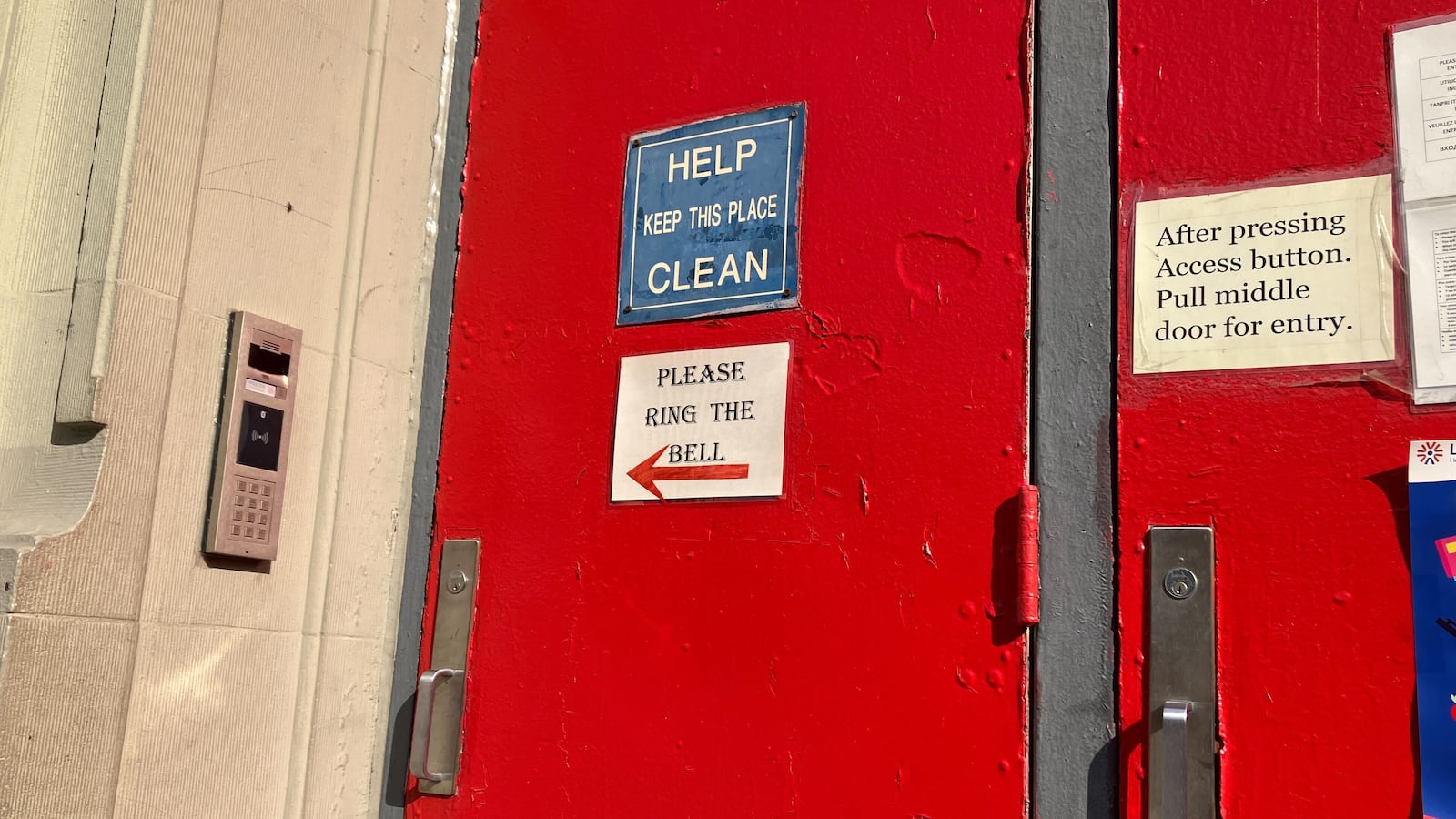

Schools that have gotten the upgrades don’t look much different from those that haven’t, except for signs instructing visitors which door to use and pointing them to a buzzer on the wall. Some signage instructs visitors to look into the camera on the buzzer panel and identify themselves. Inside, school safety agents monitor the camera and are supposed to determine whether the visitor has a legitimate reason to be there before buzzing them in.

A reporter was able to walk into two different Brooklyn school buildings that had already been outfitted with intercoms without ringing the buzzer. At one campus, the intercom worked, and the school safety agent was able to hear and see people who approached the building, but the front door was unlocked. The school safety agent at the front desk said she had not yet been instructed to lock the door.

Officials said schools can’t opt out of the program. Once the equipment is fully functioning, the main door should be locked as outlined in Education Department protocols.

School communities see the good and bad

At New Bridges Elementary in Brooklyn, Principal Kevyn Bowles said he was glad the city installed a door-locking system on his campus two summers ago. His school is off the busy thoroughfare of Eastern Parkway, and there have been a handful of incidents over the past decade where people facing mental illness or homelessness wandered into the building and had to be escorted out by the school safety agent.

That would not happen with the new system, he believes.

“That person would be stopped at the door, and [the safety agent would] actually be able to give them the direction that they couldn’t come in,” Bowles said. And in the event that an outsider tried to get in to commit harm, “this would at least create a moment of pause where that person is asked to identify themselves before they get buzzed.”

Bowles acknowledged that the system is not airtight, since it’s turned off during arrival and dismissal. And he noted that the safety agent has to manage a lot of parents buzzing in during pickup from the afterschool program, as the door is locked again after the regular school day ends. But he said there haven’t been any significant hiccups or pushback from parents.

“It has just become part of the normal procedure,” he said.

Rosa Diaz, a parent leader in Manhattan’s East Harlem, felt the door-locking systems left a “sweet” and “sour” taste. The buzzer systems could have helped in instances she has seen, she said. One time, for example, she saw a parent entering her youngest child’s school with a knife due to a conflict with a parent on the PTA. The school safety agent intervened, and no one was hurt, she said.

But she worries the locked doors will be unfriendly to families, especially in her neighborhood, where there are many asylum-seeking and undocumented families.

“There is a relief that, god forbid, someone who wants to come in and do harm won’t do so,” Diaz said of the system. “But then there are parents that want to come in and will not feel welcomed, not feel invited.”

Banks has said the intention of the door-locking system isn’t to make parents feel excluded.

“It’s not meant to keep parents out,” he said recently. “It is designed to ensure that no one is in the building who is not supposed to be in the building. And that’s the number one thing that parents care about, is the safety of their child.”

Robert Murtfeld, a parent at the Neighborhood School in Manhattan, said some parents at his children’s East Village school felt that the locked door disrupted community spirit. But he took a more neutral stance, seeing both sides.

Murtfeld, who has pushed for the city to reduce active shooter drills, hoped that the door-locking systems mean there’s even less need for multiple lockdown drills in a year.

He gained a new perspective after spending nearly every day in the school for nearly three weeks cleaning out the PTA room.

“[I] saw how the school runs all day, at lunchtime, at recess, and not just at dropoff and pickup,” he said. “So that was when I realized that it is quite deserted at certain hours, and if anybody can walk into a deserted place, maybe it’s not a bad idea to have these things.”

Amy Zimmer is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat New York. Contact Amy at azimmer@chalkbeat.org.

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.

Julian Shen-Berro is a reporter covering New York City. Contact him at jshen-berro@chalkbeat.org