This story was published in collaboration with Headway, a new initiative at The New York Times. Chalkbeat and Headway have been posing questions about the presidential election to educators and high school students since February. We have heard from more than 1,000 students and 200 teachers across the nation.

The lead-up to the 2024 presidential election has become one for the history books: A felony trial, two assassination attempts, a pivotal debate and a history-making candidate’s nomination are just some of the moments that have come to define the cycle.

Yet this watershed moment is taking place amid a level of school censorship not seen in decades, including book bans and debates over what students should be allowed to learn in history class. This year, The New York Times, in partnership with Chalkbeat, a news outlet covering education, has sought to learn more about how students and teachers are experiencing the moment.

Here’s what three social studies classes at a high school in New York City are learning about the 2024 election.

11th Grade Advanced Placement U.S. History on the health of U.S. democracy

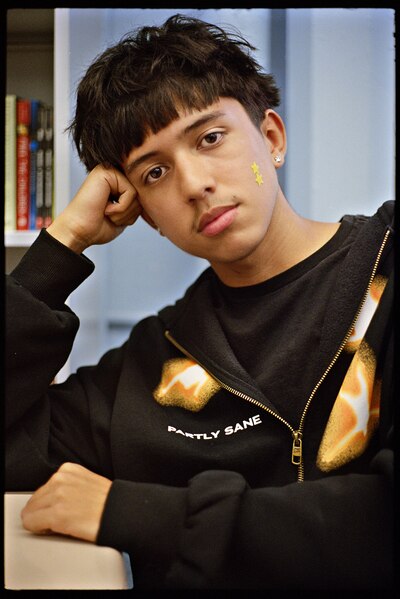

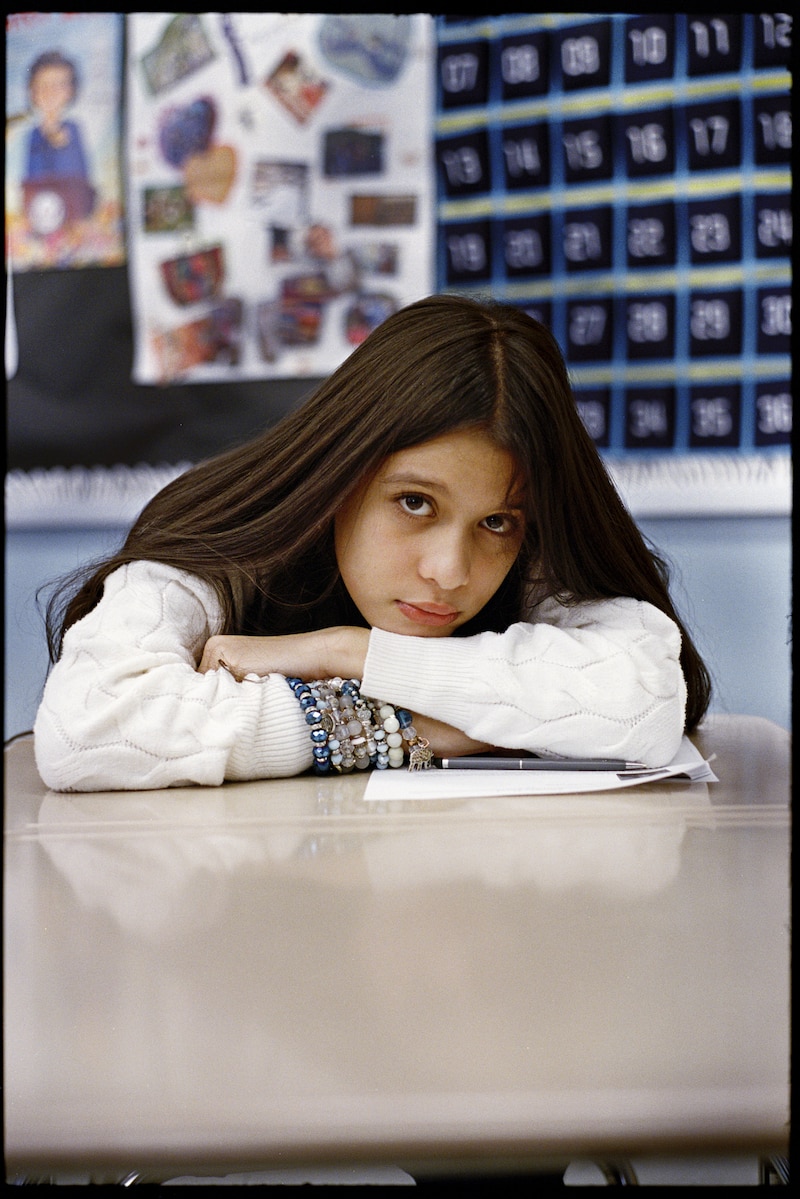

“In the debate between Trump and Harris, I feel like if I watched that and I didn’t know anything about either of them, I wouldn’t choose either one.”

— Rachel Singh, 16

Jeremy Kaplan’s approach to teaching 11th-grade Advanced Placement U.S. History is to try to meet students where they are — thinking about the topics they’re already engaging with and the issues they care about, and incorporating them into the mandated curriculum.

Given the immediacy of the 2024 election, Kaplan is using his dual role as assistant principal and teacher at the High School for Health Professions & Human Services to encourage the social studies department to incorporate election content in lessons in some way this year.

“This is the only time in our students’ high school career where they’re going to experience a presidential election,” Kaplan says he told teachers. “Whether you’re teaching ninth grade global, 10th grade global, even 11th grade history, figure out a way to teach the election, because this is our chance to teach it.”

“I feel like it’s a less healthy democracy because I don’t feel like people are getting the rights they deserve. I feel like we’re getting things taken away from us, especially as women, like abortion rights, like the overruling of Roe vs. Wade.”

— Astrid Alayo, 16

“Part of the American democracy is sick, because even though we have that you should transfer power peacefully on Inauguration Day, what happened was that a president tried to actively stop the certification of another president and not leave office.”

— Lucas Jimenez, 16

“In the debate between Donald Trump and Kamala Harris, the majority of it was just them throwing attacks at each other. They didn’t really talk about the issues that they want to fix.”

— Silvestre Mora, 16

In his class, Kaplan asked students to consider what the 2024 election says about the health of U.S. democracy. For the first few weeks of the school year, students learned about the electoral process, local and national candidates and the cornerstones of a representative democracy. The unit ended with a round table inspired by the Socratic seminar, a form of open-ended, student-led discussion around a specific topic.

Kaplan said he was inspired to create this unit by having conversations with students who seemed apathetic toward the election despite seeing content about it online.

“For me, following the news is a habit of democracy that we need to cultivate in school and history class,” Kaplan said. “And election content is a part of that, I think, because social media is a part of the news.”

12th grade Participation in Government on social media

For Mahir Syed, it just made sense to teach the 2024 election to his 12th grade Participation in Government class by beginning with the role of social media.

“That’s how they’re already engaging with the material and where they’re getting their information from,” he said. “And I want to teach them how to use social media as a tool.”

Syed asked students to think about the many ways social media is present in this election. How is it being used to persuade? Educate? Inform? Misinform?

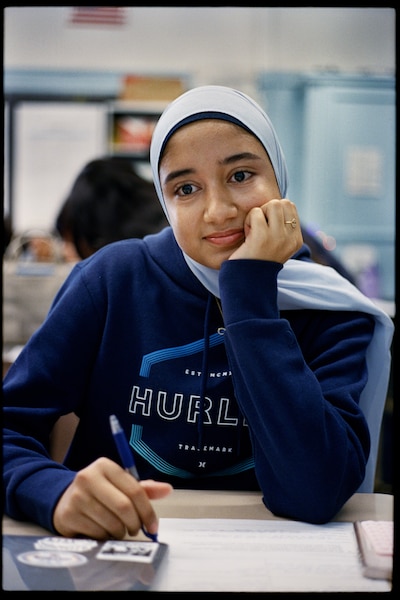

“Sometimes it’s harder for older people to differentiate between A.I. pictures and real pictures, but I think it’s also harder for us. Like some A.I. pictures are obviously A.I., but with others you can’t really tell, and I think we also can fall for that misinformation.”

— Salma Makled, 17

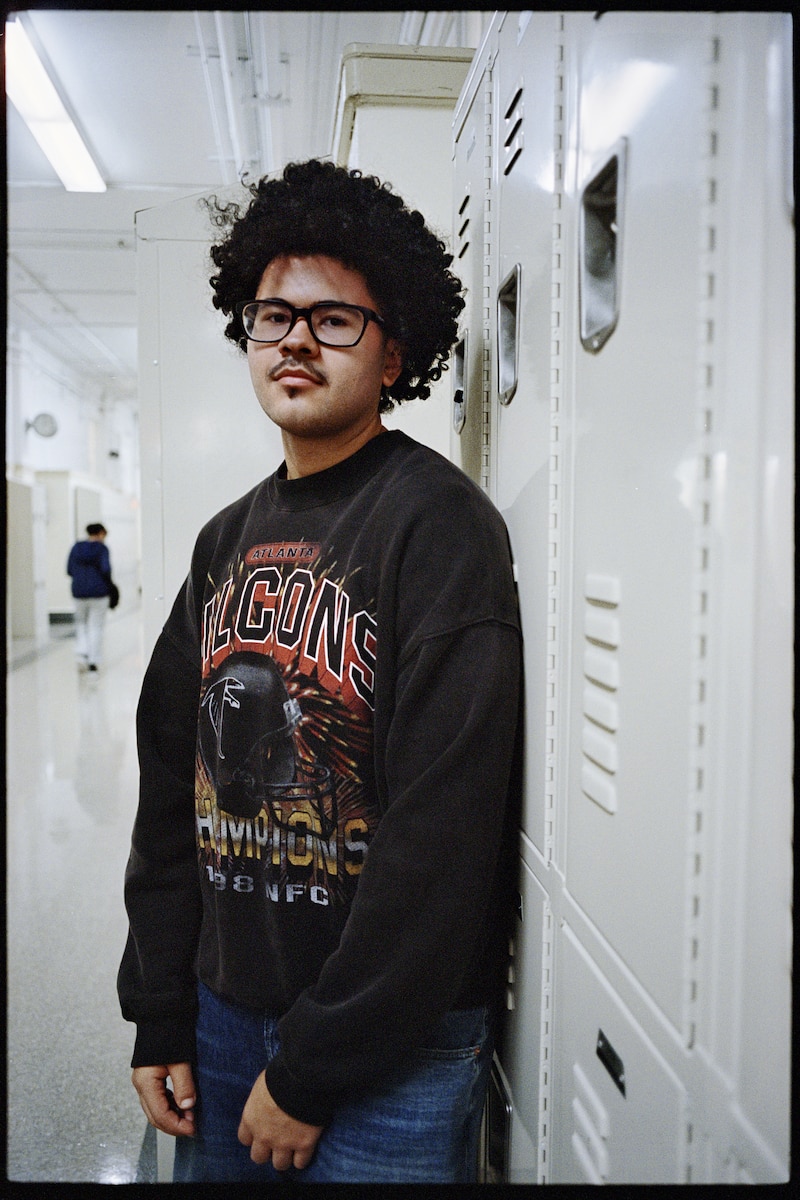

“I feel like social media has allowed me to understand the opposing side better, because I see both sides. Like in memes, I’m seeing memes from Kamala’s side hyping up Kamala and bringing down Trump, and on the other side I’m also seeing how Trump supporters are memeing him to uplift him while also bringing Kamala down.”

— Geoffrey Fletcher, 17

“I would say the majority of young people are getting educated by social media about the election, which can be a good thing, but also negative because people can cherry-pick clips of candidates. You can be educated from both sides, even though sometimes young people tend to just side with one side and not be open-minded to the other side, which I disagree with.”

— Jesus Peralta, 18

“I know when I’ve seen something and then do a quick search about it, sometimes it kind of leaves me stumped. Like, if you’re leaning more on one side, but then you find out something else. It makes me think that none of these candidates are all that good for us.”

— Melanie Quizhpe, 17

The subject of artificial intelligence and its role in spreading misinformation came up almost immediately. Students shared examples of A.I.-generated content related to the election that they had seen online, such as an image of former President Donald J. Trump standing in Hurricane Helene floodwaters.

After Syed urged them to think about who is most at risk for being tricked by this content, the students debated how different generations interact with social media.

Sunaya Bhoodai, 16, shared that she feels particularly compelled by Vice President Kamala Harris’s social media campaign. That prompted other students to share how they engage with political content online, namely that they appreciate that they can use it to see different points of view, but also that they tend to not fact-check what they are seeing.

“I usually find myself researching the points made by people who I don’t support, because I feel like I can instinctively trust the people that I do support,” Geoffrey Fletcher, 17, said.

“Do you think that we do it enough where we actually try to go out and look for what the other side is saying?” Syed asked the class in response. He reminded them that algorithms can potentially skew what they are exposed to. “Because of confirmation bias and us only looking at our side of the coin, does that lead to dangerous outcomes for an election cycle?”

“Yeah,” Jesus Peralta, 18, said, “Because you’re so fixated and focused on one side without being open minded to the other side.”

He added: “Maybe your side is wrong, but you’re just so biased against supporting the other side.”

“There needs to be more balance.”

9th grade world history on the candidates and their policies

Down the hall, in ninth grade World History, many of Jennifer Alvarez’s young students were engaging with the topic of American democracy in a classroom setting for the first time.

So Alvarez started with some large, but basic questions: What values do the students hold? What are the beliefs and policies of the presidential candidates?

Several students expressed a personal connection to the subject of immigration. In this New York City classroom, Trump’s rhetoric on the subject was a flashpoint. Sadiya Sultana, 14, referred to part of a class text describing a Trump rally where the candidate talked about plans for expelling migrants.

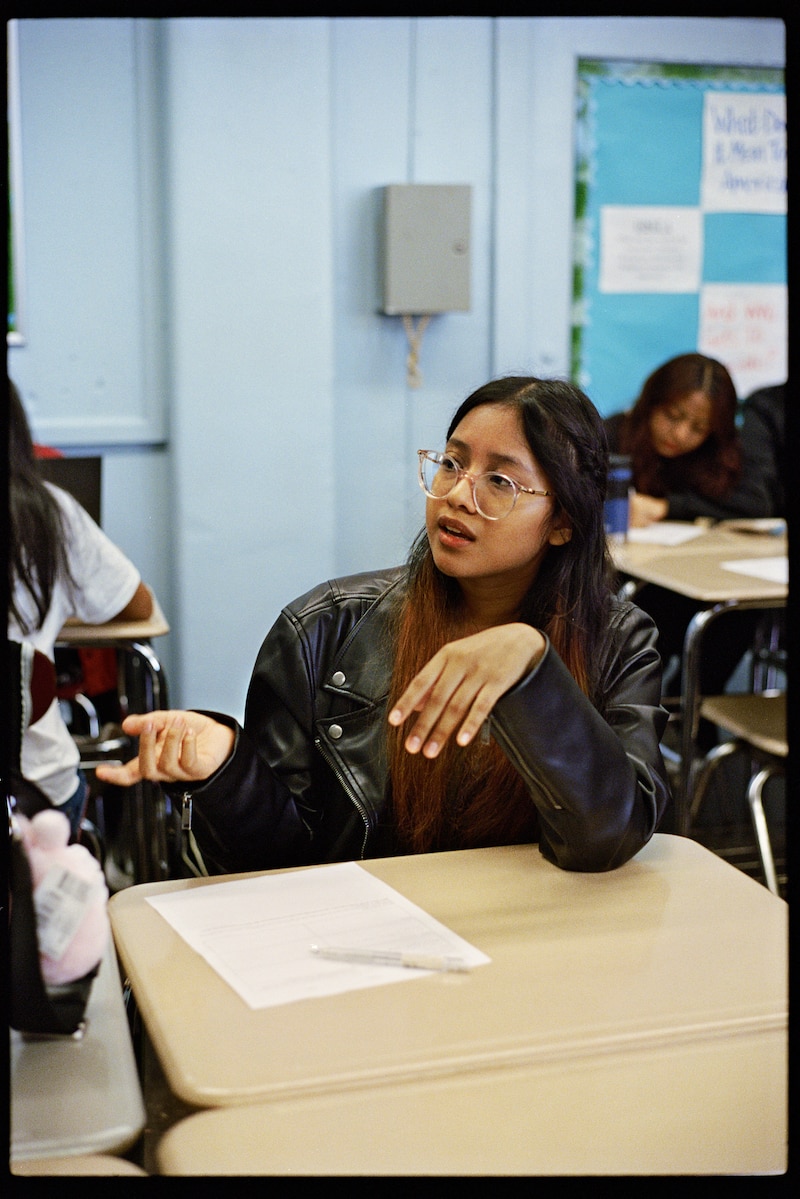

“When I first saw Ms. Kamala Harris’s advertisement campaign on TikTok, back then I didn’t really understand or care for the political world, but when I saw her advertisements, it kind of changed my perspective on a lot of things.”

— Mariely Bueno, 14

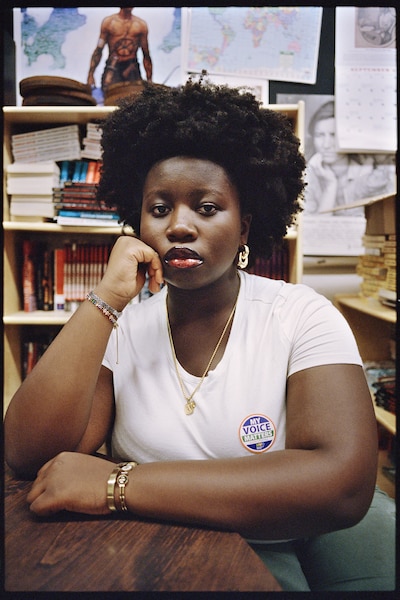

“I feel like young people are the ones making tomorrow. I feel like the older generation is set in their old mind-set while the world is changing every day. And I feel like we are part of that change.”

— Abeyuwa Uwoghiren, 14

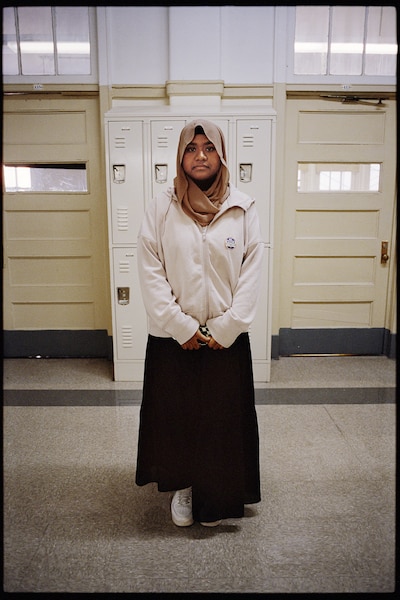

“A lot of the things that impact laws can happen due to student influence. Like a lot of protests are coming from young people. So I think we will have a lot of influence in this election.”

— Sadiya Sultana, 14

“The thing that really stuck out to me was when he mentioned that when he’s going to remove the immigrants, he said it would be ‘bloody,’” Sultana said. “That really just stuck to me. I’m an immigrant myself, so imagining that happening to other immigrants, it really breaks my heart.”

Abeyuwa Uwoghiren, 14, echoed her classmate’s sentiment, but shared that she was also taken aback by Harris’s relatively tough stance — Harris has promoted her support for legislation that would close the U.S.-Mexico border if daily crossings reached a certain average over a week.

“Everybody comes to America for a reason,” Mariely Bueno, 14, said. “America is made up of immigrants, so I believe treating immigrants like that, it just isn’t fair. Young people can maybe do petitions or protests, or make proposals to the government to make change.”

That, Alvarez said, was the point of the lesson. Ordinarily at this point, the ninth-graders would be learning about how different forms of government around the world have influenced the United States. But the 2024 election provided Alvarez with the opportunity to make the topics of democracy more immediate and tangible for her students.

“It’s about giving them the information they need to develop their thinking to become an informed citizen,” Alvarez said. “Because that’s what social studies is, right? It’s how do I fit in the puzzle, and what can I do to be a change agent?”