The night I returned to New York City at age 5, the city felt surreal — bustling, vibrant, and intimidating. As my parents, older sister, and I got into the taxi, the city lights appeared to converge and become one. Everything seemed larger here. As the cab slowly pulled away from the airport, so did my sense of reality. From the towering buildings to the flashing signs to the rushing cars, it was all so different from the villages of Fujian province, China.

The taxi took us to the Borough Park, Brooklyn, apartment where we would be staying. When we walked in, there were boxes, furniture, appliances, and bicycles crowded into a roughly 144-square-foot living room. How can anyone live like this? I thought.

My family of four slept in a room that was smaller still, crammed with a bunk bed, a square table, and two chairs. As the clock struck midnight on what would be my first full day back in New York, I sat on the bottom bunk and ate takeout. I was full of curiosity and excitement, yet there were certain nuances to my feelings. Who were my parents? Why had they come all this way to a foreign land? And most importantly, why had I lived so far from them?

I was 7,000 miles — and a virtual world away — from Fujian, where I had lived alongside a pond overgrown with lily pads, where the breeze would fly across my face, where the sound of crickets would penetrate the otherwise silent night, and where my grandma would pluck chickens for us to cook and eat. Everything was calmer and quieter there, on our block with only a couple of houses.

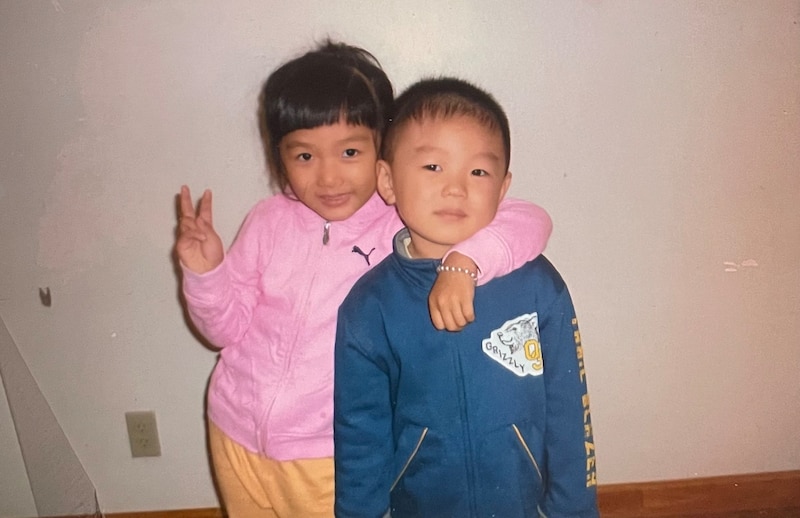

I soon learned that I hadn’t always lived so far from my mom and dad. My parents explained that I was born in Flushing, Queens, less than 20 miles from Borough Park. But like many immigrants, my parents worked grueling schedules at minimum-wage jobs — my mother in a nail salon with minimal training and my father as a chef at a Chinese buffet. Overextended and unable to support a family of four, they sent my sister and me to live with our grandparents in China.

For my parents, America — a nation that purports to value individual liberty, growth, and prosperity — became nothing more than the place where they resided as they saved money to bring us back to them.

All this makes me what some researchers call a ”satellite baby.” Lacking affordable child care, many Chinese immigrant families send their American-born babies to live with family members in China. When the kids are ready for school, at around age 4 or 5, many of those satellite babies return to the U.S.

Because of this arrangement, I had the joy of getting to know my grandparents. But it came at a cost: I didn’t really know the very people who created me. We were family, and we were strangers — so close, yet so far apart.

In the months after I returned to my parents, I was often nostalgic for my simpler life back in China. I would think about the small shop in town where my sister would buy the most pointless toys and about the local theater where performers dressed in elaborate costumes and painted their faces to tell the story of an emperor’s favorite concubine. This longing is what happens when you’re caught between two worlds — one that holds the joyful memories of childhood, and another of a new and confusing country.

People sometimes ask me if I could go back, would I do it all again. My answer will always be yes. These memories are reminders of a time when I was smaller, but when my heart felt a little fuller.

In Borough Park, my parents enrolled my sister and me in school. As a little Chinese “immigrant,” I spoke no English. Nor had I developed a sense of independence, and I would often cry when my mother left for work. In America, life felt like a rollercoaster, terrifying but also thrilling.

By fifth grade, though, I stood on the podium at Brooklyn’s P.S. 69 Vincent D. Grippo School and gave a valedictory speech. Somewhere along the way, the naive village boy had become an industrious student in the big city. I couldn’t grasp how rapidly my life had been transformed.

Now, about a decade after leaving China and returning to New York, I’m a student at Staten Island Tech, one of a handful of elite specialized high schools in New York City. Sometimes I wonder: Does my success mean that my parents’ hard work has finally paid off? Does it mean they are proud of me?

I feel constant pressure to succeed. Not for my peers, not for my teachers, and not even for myself, but for my parents, who still work humble, low-wage jobs. This pressure doesn’t come from them, who urge me to “do what makes you happy,” but rather from within. Sometimes, the very opportunities that are supposed to liberate me feel more like a burden.

I know I’m not the only one who feels this way. Many children of immigrant parents experience this overwhelm. For us, the American Dream can feel like a debt we can never repay our parents.

We were family, and we were strangers.

When I first returned to America, I didn’t even know what the American Dream was. I soon came to understand it to be the idea that if you work hard, you can succeed. I know now that it’s not that simple, that factors such as personal and professional networks, perseverance, health, and luck also play a role. Still, I always tell myself that I could be working a little harder, like when I finish taking a test and feel pessimistic about the outcome, despite having studied so hard.

The pressure could be something I, along with millions of children of immigrants, navigate our whole lives. We learn to coexist with it. Success in high school and beyond feels like a given. And working in a field that doesn’t pay well or waiting for the perfect job isn’t really an option because we want to provide lives of comfort for our parents, who never lived such lives.

I feel the weight of it all because, deep down, I know that I am a big part of my parents’ American Dream.

Ocean Lin, a member of Chalkbeat’s 2024-25 Student Voices Fellowship class, is a high school junior who wants to pursue a career in chemistry. He hopes to make a difference and share authentic stories. Ocean started the Instagram poetry account Tide Tales to give marginalized groups a platform for creative self-expression.