Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to keep up with NYC’s public schools.

New York City students received fewer suspensions last school year, though the number of lengthy punishments ticked up, new data showed.

Schools issued 27,724 suspensions during the 2023-24 school year, a 2.4% decline from the year before when the punishments roared back to pre-pandemic levels.

Principal suspensions, which last five days or fewer and are typically served in school, declined by more than 3%. But superintendent suspensions, which stretch six days or longer and are served at outside suspension sites, ticked up about 1% to just over 6,200. Most suspensions are capped at 20 days, but in some cases can stretch for months and up to an entire school year.

The total number of suspensions remained below the nearly 33,000 issued in the school year before COVID hit, however suspension rates have returned to similar levels, as fewer students are enrolled in the city’s public schools. (The figures do not include charters.)

In the wake of the pandemic, some observers worried that suspensions would surge as concerns about student mental health and behavior multiplied. Unlike his predecessor, Mayor Eric Adams hasn’t prioritized reducing suspension rates — sparking fears among discipline reform advocates that his tough-on-crime posture on public safety could trickle into schools.

But Adams has not sought to dramatically change the school discipline code, which was overhauled under former Mayor Bill de Blasio to nudge schools away from suspensions. And facing pressure from advocates, Adams has largely kept restorative justice programs in place, which include peer mediation and alternative methods of talking through conflicts.

“It does feel like we’ve made inroads,” said Rohini Singh, director of the school justice project at Advocates for Children, which helps low-income families navigate the suspension process and has pushed to reduce punitive punishments. “Talking about the harm of suspensions and exclusionary discipline is not such an outrageous thing anymore.”

Many — though not all — studies show that suspensions hurt students academically, including research in New York City that found the punishments contributed to students passing fewer classes and increasing their risk of dropping out.

Singh noted that there were still troubling disparities in the suspension statistics. About 38% of suspensions went to Black students and a similar share went to students with disabilities, even as fewer than 20% of city students are Black and about 22% have a disability. Suspensions of Latino students were more in line with their share of the student population.

At the same time, white and Asian American students were significantly less likely to be suspended relative to their share of enrollment.

City officials said they are continuing to encourage schools to use alternatives to suspensions such as restorative justice. Schools are also expected to monitor disparities in suspension rates between different student groups, officials added.

“We are proud to see an overall decline in suspensions,” Education Department spokesperson Jenna Lyle wrote in a statement. “Through promotion of restorative measures and an emphasis on social-emotional learning, we aim to continue this downward trend while tackling historic inequities.”

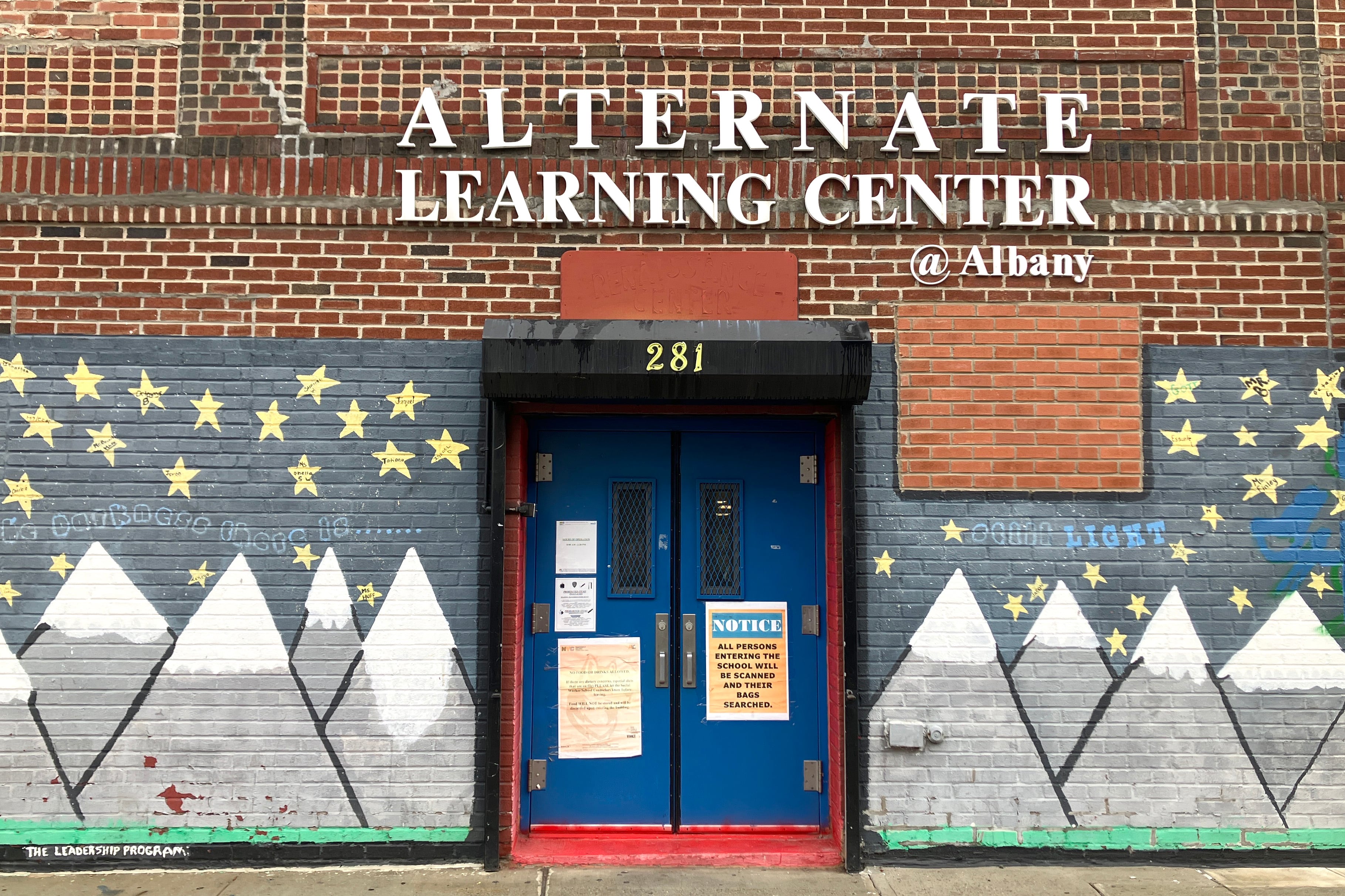

In addition to longstanding disparities in which students are most likely to be suspended, advocates also worried about the uptick in lengthy superintendent suspensions — which require students to attend school at suspension centers and are even more disproportionately issued to Black students and children with disabilities. Students who received long-term suspensions previously told Chalkbeat that the suspension centers can feel chaotic, and academic expectations are often low.

In representing students in suspension proceedings, Singh said some schools appeared to “overcharge” students for relatively minor fights, but acknowledged it is difficult to know exactly what is driving the trend citywide.

“There’s still more work to be done” to bring those suspension rates down, she said.

The city’s suspension data is also incomplete. The Education Department did not include breakdowns for students in foster care, which were required under a 2023 tweak to city law. A department spokesperson said they were working to compile the statistics but did not offer a timeline for releasing them.

“This is very worrisome that they’re not including that data,” said City Council member Rita Joseph, who authored the bill and helms the education committee. “I wanted to capture the data so we can do better in providing support for these students … They’ve already gone through enough trauma.”

The full suspension data was also required to be shared publicly by the end of October, but was posted weeks late. A department spokesperson did not respond to a question about why the city has not published the statistics on time in recent years.

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.