Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to get essential news about NYC’s public schools delivered to your inbox.

Few New York City schools have more at stake in President-elect Donald Trump’s second term than those in the Internationals Network for Public Schools.

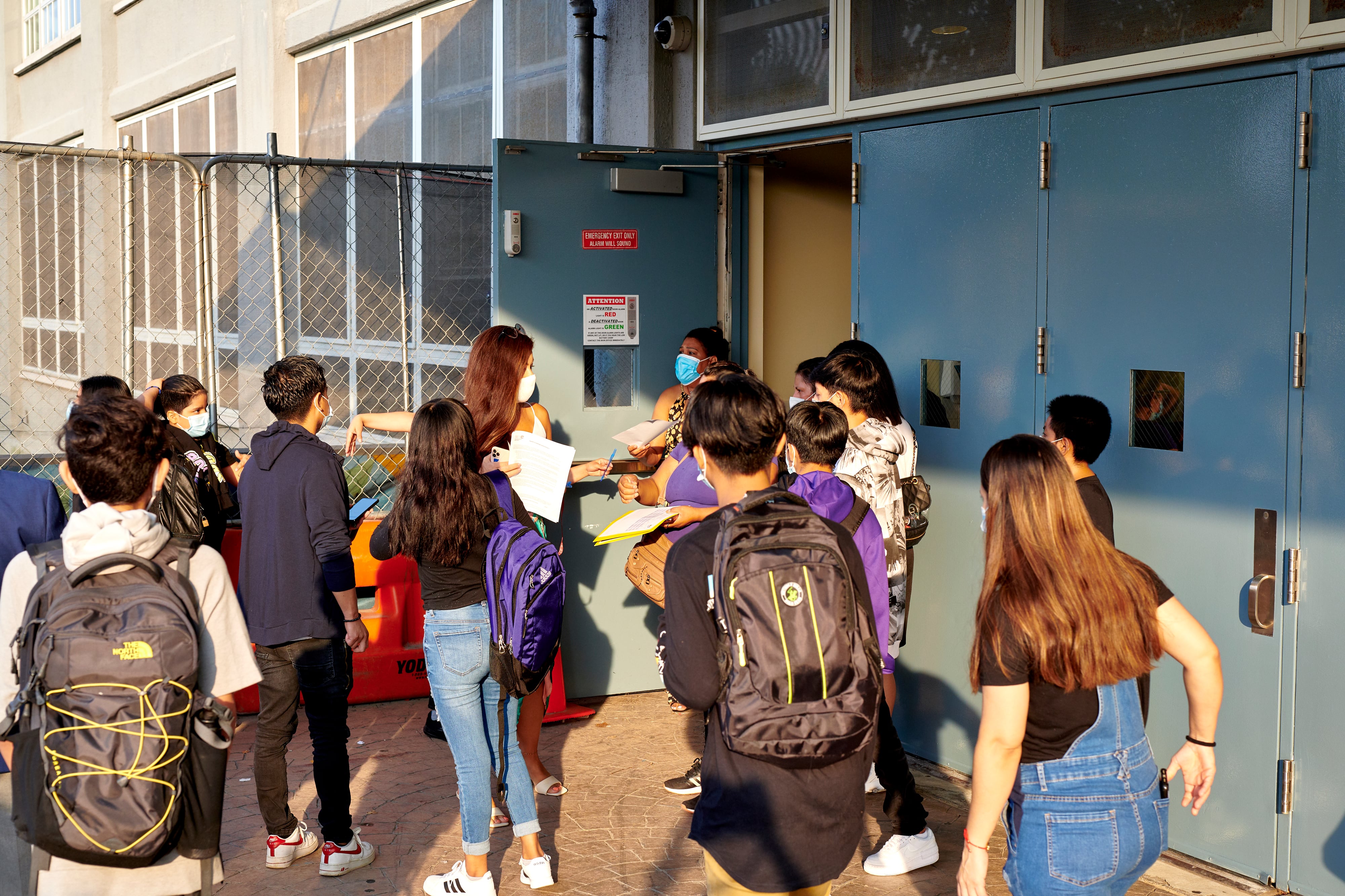

The nonprofit network helps operate 17 public schools across the five boroughs that cater exclusively to newly arrived immigrant students, serving as a national model for educating newcomers.

Over two decades, the network has weathered shifting immigration patterns and policies and played a central role in educating many of the estimated 48,000 newcomers who have enrolled in city schools since summer 2022.

Now, as Trump lays the groundwork for a promised “mass deportation,” and state and local officials scramble to respond, the network is watching closely and making its own preparations.

Local law and Education Department regulations prohibit non-city law enforcement from entering school buildings except under specific circumstances, and city officials are training district superintendents, principals, and NYPD school safety agents on those protocols, people familiar with the plans said.

But fears and lingering questions remain pervasive.

Trump is likely to roll back a longstanding internal Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, policy against making arrests at “sensitive locations” like schools, NBC News recently reported, though it wasn’t immediately clear how that would affect the city’s local provisions restricting federal agents from schools. Mayor Eric Adams, who met Thursday with Trump’s incoming “border czar” Tom Homan, told reporters after the meeting he’s looking into increasing the ability of local law enforcement to work with ICE to “go after those individuals who are repeatedly committing crimes in our city.” Adams said “law-abiding” immigrants should continue to use public services including education.

And even if immigration enforcement doesn’t take place at schools, the shockwaves are likely to reach students, who may face deportation cases themselves or see family members expelled from the country. The fear and uncertainty can also have their own corrosive effects by keeping kids and families away from schools and exacerbating attendance and enrollment challenges, educators said.

New York City’s Education Department officials reiterated its commitment in recent weeks to keeping schools safe zones from immigration enforcement.

“Our schools are safe harbors for our children and they will remain so,” Chancellor Melissa Aviles-Ramos said at a recent meeting of the Panel for Educational Policy.

Leaders at the Internationals Network are trying to address families’ concerns while reining in some of the waves of fear they see gripping their communities.

“Our job is to keep hope alive for these students,” said Claire Sylvan, the founder and senior strategic director of the Internationals Network and a former teacher. “I’m not saying that things are going to be easy, but I’m saying that these are our children, and we are dedicated to ensuring that they are safe, welcome, and come to school.”

Chalkbeat spoke to Sylvan and Lara Evangelista, the network’s director and a former international school principal and deputy superintendent, about how they’re approaching the coming years, lessons they’ve learned, and what other educators can draw from their experiences.

The interview was edited for length and clarity.

Can you lay out what protections exist and some basics that schools and families should know?

Claire Sylvan: On the national level, there’s Plyler, which is a 1982 [U.S. Supreme Court] decision that says any student who’s eligible for K-12 education has a legal right to attend school at no cost, like any other resident.

There’s also, to date, protections around sensitive areas that Homeland Security issued.

New York City Public Schools has a very strong policy. They have already re-issued it with an incredibly strong email to all 1,600 principals. They followed up with training of superintendents. They’ve been incredibly collaborative with us and other immigrant organizations in terms of thinking through, ‘What do you need to do on the ground?’ They’re not only training the school personnel but the school safety agents, who technically are supervised by the Police Department.

They’ve been open to all of our conversations, and they’re providing contacts to schools in terms of community-based organizations. Our starting point is that schools need to be warm, welcoming, and supportive environments, and that’s still our priority, because that has to come first for students to learn. New York City has provided a framework that we can do that well within.

How do you balance being realistic about real concerns without overly causing fear that would keep people away from schools altogether?

Lara Evangelista: We’re realistic with families. We’re not hiding information. But we’re also sharing with them that there are policies that we will uphold that New York City has put in place to protect you.

Our community-based organizations support families with making sure their documents are in order, if they have something that’s expired, that they update it, that they understand what their rights are, that, if needed, they have accompaniment plans for their children if families are separated for some reason. We want to give them those tools to prepare them.

But we’re balancing, like you said. We don’t want to just feed into fear. We want to be realistic, but also continue to create supportive places for them. Because we want to take care of our young people emotionally. It’s how we’ve been set up from the beginning, so we’re really leaning into that to support our students and our families through this.

How does talking about an ‘accompaniment plan’ go with families?

LE: One of my first cases when I was a principal was I had a young person call us and say, ‘My parents were picked up selling clothes. What do I do? I have siblings.’And so we learned then that we needed to make sure our families were prepared.

We don’t take that on ourselves, but through legal partnerships and so on, we run workshops and let families know that like this is something they should have in place so that if people are separated, if the major earners in the family are gone and the children are left, what happens?

How much of what you’re doing now, or what you’ve done since the election, is standard procedure for you, and how much is different?

LE: We’ve always done this. I was a principal a long time. And we had situations in the Obama administration where families were just deported, and we had to manage that.

We’re lucky in that we have relationships with partners that we can lean into for these kinds of supports. We’ve always had legal screenings for families so that they can understand how to manage their paperwork. A legal organization will come and meet with families and students and, if they choose, can talk to them about their immigration situation.

CS: Some schools choose to do that on an open school night. You talk to your kid’s teacher, but you also go down the hall and have this conversation.

Can you talk about what you both saw during the first Trump administration and any lessons that you are taking from that and applying now?

LE: In the beginning, I remember some parents were afraid to come to a parent workshop, Open School Night, a parent teacher conference, because they were worried something would happen.

We had to really spend a lot of time communicating with families about our role, what the policies were, why they were going to be safe in our buildings, and really build relationships with families so that they did feel safe.

But I think the other thing was just how incredibly resilient our families and students were during that time. While we did have some students who dropped out or were discouraged, the vast majority of them, they just kept going. They were like, ‘Look, I’m here. I have dreams. This is what I want for me and my family.’ They continued to pursue those dreams in spite of all that, so that was really inspiring for us as educators.

At this point, what is your biggest fear? And on the flip side, are there things that you’re doing now that you feel most hopeful about? What would you like to see happen that might ease some of those concerns?

CS: I can’t tell you how many individuals and people have approached us as an organization or our schools or our leaders and said: “How can we help?” There is a community of people who care about our students.

LE: It’s really, really hard to predict what might happen. There’s a lot out there, and we don’t want to be in a situation where we’re just sharing all of this information that may or may not happen. We know what the situation is now, we know how to prepare from our work in the past, and that’s what we operate under. I don’t worry about students disappearing and not coming to school. There’s lots of rhetoric out there about what might happen in terms of deportation, but I try not to live in that space because our students do give us so much hope.

CS: I don’t have a crystal ball, but I know we have to keep our eye on the ball, and it’s going to move around the soccer field an awful lot.

Michael Elsen-Rooney is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Michael at melsen-rooney@chalkbeat.org