Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to get essential news about NYC’s public schools delivered to your inbox.

A sweet smell wafted through a classroom of second and third graders as a pair of students in red aprons measured oats for a granola recipe.

Next door, a group of fourth and fifth graders peeled garlic cloves to make fresh garlic bread.

It was just another Tuesday at Central Park East 1 elementary school, where every classroom is equipped with an oven and refrigerator, and every day students cook or bake a snack as part of their many routines.

Deborah Meier founded the school 50 years ago with a mission: to build a democratic educational model where teachers collaborate to build their own curriculum rooted in hands-on, project-based learning; parents have a voice in their children’s education; and children have ample choices during their daily “work” or “project” time.

Central Park East spawned a movement of progressive education in New York City and beyond, and Meier won a MacArthur “genius” award in 1987 for her work. The school’s child-centered model, following where students’ interests take them, is facing some headwinds at a time when the nation’s largest school system is leaning on curriculum mandates and data-driven assessments.

“They mandate everything: how much time you spend on something, how you ask your questions. It’s utterly entirely against what good learning is about,” Meier told Chalkbeat. “What’s important is to pay attention to what is working with each child.”

Offerings at the small school, in many ways, feel more like a private school, Meier said — including the lack of emphasis on standardized testing. Kids bring back materials from their regular Central Park outings to use for art projects and other investigations. They go ice skating weekly. They have Monday morning all-school sing-alongs. And there’s an annual camping trip for fourth and fifth graders, many of whom have never spent the night away from their families. Students call their teachers by their first names, and the classes are mixed ages (except for prekindergarten), with students typically staying with the same teachers for two years. The mixed classes push the younger kids up, in some ways accelerating their learning, while giving the older kids leadership opportunities, families said.

Despite the curriculum mandates and increased focus on testing systemwide, the school is staying true to its ideals, with educators and families committed to continuing its legacy.

A letter to families posted last spring on the school’s website explained how CPE1 would this year be required to implement Into Reading, one of three literacy curriculums mandated citywide. The school planned to combine the “best” of Into Reading with material “we think will serve our community,” the letter explained, praising the curriculum for having a Spanish-language version but critiquing its omission of LGBTQ voices and how it tackles bias and prejudice. (In Florida, where the curriculum is also used, elementary schools can’t teach about gender or sexual orientation, the letter explained.)

Gabriel Feldberg, CPE1’s principal for the past eight years, declined to comment on the letter, but he noted that CPE1’s students are high performers when it comes to the Acadience assessments students are given three times a year, with more than 21 out of 24 of the school’s second graders currently reading on or above grade level.

“Our reading is in the service of our wider educational mission, not in the pursuit of any external goals,” said Feldberg.

Times were different when Meier opened the school.

“She did her work at a time when her district and her city valued the kind of work she did and was very public about what was wonderful about it,” Feldberg said. “Data-driven imperatives have changed how we define quality in education.”

For Meier, education should help children become “citizens of the world” and active participants in democracy, she told an audience of students, alumni, and former staffers at an October event celebrating the school’s 50th anniversary. To participate in democracy, kids need to experience living in one, said Meier, who at 93 is currently fundraising for a documentary about the first graduating class of the East Harlem secondary school she opened and how they embodied the democratic ideals she sought to create.

“It’s one of the fundamental things that we hoped that schools could be: places where children learned alongside with their teachers and their families,” she said, “and have a say, have a voice that matters.”

Teaching about identity and race through self-portraits

When CPE1 opened its doors in 1974, it served primarily Black and Latino students from low-income families who were often written off by many educators, Meier said.

“Schools of education during my time would say things like, ‘Black children don’t have any language when they come to school,” Meier said. “Kids have a hard time learning from people who disrespected them and their families.”

The school’s demographics have shifted since then, but the diversity of its staff and student body has become one of its hallmarks. Roughly 44% of its students are Latino students, 25% are white, 15% are Black, and 8% are Asian American — which is more integrated than most New York City public schools. About half of its students are from low-income households, which is less than the citywide average of 75%.

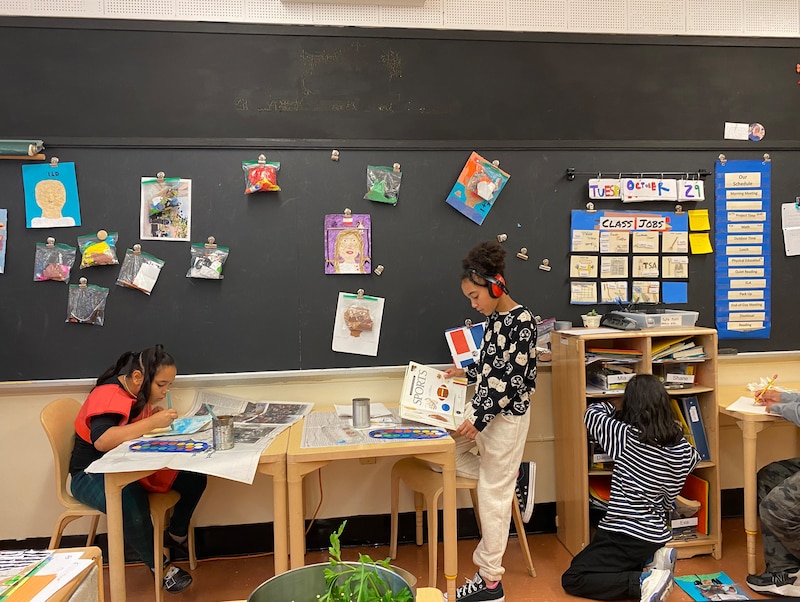

The school emphasizes identity, with students creating a series of self-portraits each year that hang in classrooms and the hallways.

“We are very explicit about talking about identity but also about race and racism,” Feldberg said.

On a recent morning, several clusters of students in the mixed second and third grade class were cutting and gluing bits of construction paper and other materials for mosaic-style self-portraits. One student, who was struggling with how to depict his nose, approached the principal.

“Gabriel, I need help,” the student said.

Feldberg grabbed a mirror, and he and the student observed the shapes of their noses.

“What do you see,” Feldberg asked as the two engaged in a lengthy discussion about the differences of their nostril shapes.

Students’ self-portraits are compiled in a “recollection folder” students receive in the spring of fifth grade to help them reflect on their journey as learners and the things that they’ve been passionate about, Feldberg said.

“You will get to rediscover your younger self and think about who you have been,” Feldberg said.

CPE 1 parent Kaliris Salas-Ramirez, said her older son, now in middle school, “always felt seen” at the school.

A former member of the city’s Panel for Educational Policy, Salas-Ramirez credits the school with inspiring her to become a parent leader. Nearly a decade ago, she helped oust a principal the Education Department installed at the school, who clashed with the community’s progressive bent. She’s proud that her sons are following suit: In pre-K last year, her younger son’s class staged a protest for being excluded from the school’s dance classes through the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater.

“It’s really hard to replicate what happens at CPE,” she said. “Kids just really push themselves to think beyond.”

Cultivating social-emotional learning without a pre-packaged curriculum

CPE 1, like many schools across the city, has lost students in recent years. The school, which gives priority to students across East Harlem’s District 4, is surrounded mainly by public housing with a sprinkling of new construction. Some families have been priced out of the area, Feldberg said.

The school is serving about 170 kids this year, down from its target of 186, with its pre-K class hit hard by enrollment dips, the principal said.

Though the school does not use a commercially made social-emotional curriculum, Feldberg said, CPE1 prides itself on infusing those practices throughout the day. The school is intentionally small so that staffers can know their students well, and students can know each other well, too.

On a recent morning, about a dozen pre-K students were busy building with blocks. At the start of the year, kids work on individual projects before they begin more complex collaborations. The teachers incorporate literacy as the children work, with a “word wall” where students can find words to add to their construction projects. One girl grabbed the word “playground,” which she then painstakingly wrote on a small piece of paper that she taped on a brick in her work area.

Another student, Samir, was stacking blocks to build a high tower near the wall of words, but as other students walked over there, his blocks toppled over.

“Are you OK?” Marilyn Martinez, one of the teachers, asked Samir.

“Everyone freeze,” she said to the class. “Can we identify what the problem is?”

“They knocked down the blocks,” one girl said.

“They knocked down the blocks,” Martinez repeated, “but what seems to be the problem?”

Samir started crying — one of the blocks had hit him on the head as his structure collapsed. Another teacher took him to get ice from the nurse, and Martinez talked with the rest of the group.

Martinez asked the kids a series of questions to help them understand what happened — the kids got too close to Samir’s tower — and how they could “walk safely” to and from their work areas in ways that wouldn’t interfere with someone’s project.

“Samir got hurt,” Martinez continued. “What can we do to help Samir out?”

“Give him a hug,” one child said.

Martinez said they could ask him if he wanted a hug when he came back, noting that he might not want one.

“What can we do right now to help him out?” she asked.

One student offered to help clean up his bricks. Another offered to help him rebuild. Martinez suggested they can help stack the bricks in neat piles to make it easier for him to build when he returns. Two kids got to work.

For Feldberg, the pre-K construction incident reflected the school’s approach to social-emotional learning. It illustrated to the kids how they are “accountable to the group,” and how they needed to be aware of each other’s work and how they could have an impact on others.

“When you have the experience of knocking down someone’s blocks,’’ he said, “you learn about your interconnectedness.”

In a classroom at another school, that situation might have been handled much differently — and in a lot less time. But creating a sense of interconnectedness and cooperation has been a throughline across the school’s half a century.

For Meier, the school’s foundation has always rested on developing a sense of caring for others and their community, which ties back into her notion of participating in democracy.

“Caring is a very important part of being a good citizen,” she said. “Accepting others, listening to others … We can sometimes disagree with someone but still find some of their ideas interesting and provocative.”

Amy Zimmer is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat New York. Contact Amy at azimmer@chalkbeat.org.