A few weeks after Election Day, a former student of mine, now a New York City public school teacher, reached out by email. She had just hosted a group of teacher friends at her apartment to think about and discuss “where we go from here as educators. One thing that kept coming up is the insistence from the city and their administrators alike that teachers remain “neutral” when talking to students about the election results and the upcoming Trump administration.”

She called the instructional guidance presented on a slide at her school “murky,” because, referencing city policy, it advised:

“Schools have an obligation to create a politically neutral learning environment. While presidential elections are a time to help teach and foster civic engagement, NYCPS employees must refrain from advocating for their preferred candidates or political parties, including refraining from wearing any items advocating for a candidate or political party.”

She went on to tell me that “warnings that our school administrations have issued make it feel as if no speech related to Trump’s policies or the impact that they may have on our school communities is permissible.” Her colleagues, she said, were “fearful about speaking truth,” lest it be labeled political speech.

Despite the guidance’s vague reference to a “politically neutral learning environment,” the rest of the text refers to partisan campaigning and not generic political issues.

Classroom teachers are, in fact, obligated to address political issues under New York State law and the state’s Civic Readiness Initiative. A city regulation, meanwhile, states that the expectation of neutrality “does not preclude school personnel from discussing or distributing information about election issues in connection with legitimate instructional programs and activities.” Post-election, New York City Public Schools updated its ”civics for all” resources for this purpose.

Within that framework, teachers are not only encouraged but also required to teach post-election matters in a factual manner within the context of the curriculum. These lessons can take place in social studies but also in science, math, English language arts, and arts — whenever they are relevant. Even if the city’s neutrality guidance is interpreted to go beyond partisan electioneering, the word used is “neutral,” not “neutered.” Teachers should take strength from that difference and meet the moment accordingly.

This is not Florida, and even there, a recent settlement over “Don’t Say Gay” legislation makes clear that discussion of so-called banned topics, such as sexual orientation and gender identity, is permissible, even if those topics cannot be part of the formal curriculum in certain grades.

In New York, marginalized individuals and groups are protected and may have full representation in the curriculum, as do hot-button issues, such as climate, trans rights, gun violence, and immigration. Educators must present this material responsibly and without demeaning individual students or those with differing views, but those considerations should enrich classroom discussions, not silence them.

I’d add that when planned, intentions to teach controversial topics might be brought to the attention of parents and school leadership, not for a veto but for possible discussion, and so those involved are prepared for any student or community response. Similarly, after-the-fact notification of unplanned classroom conversations may be advisable.

New York State law and curriculum standards — along with the ethical obligation to help students understand their world and build critical thinking skills — obligate teachers to resist perceived pressures to avoid controversial topics in context. This takes skill, and school leaders should provide professional development to help teachers navigate these hard conversations.

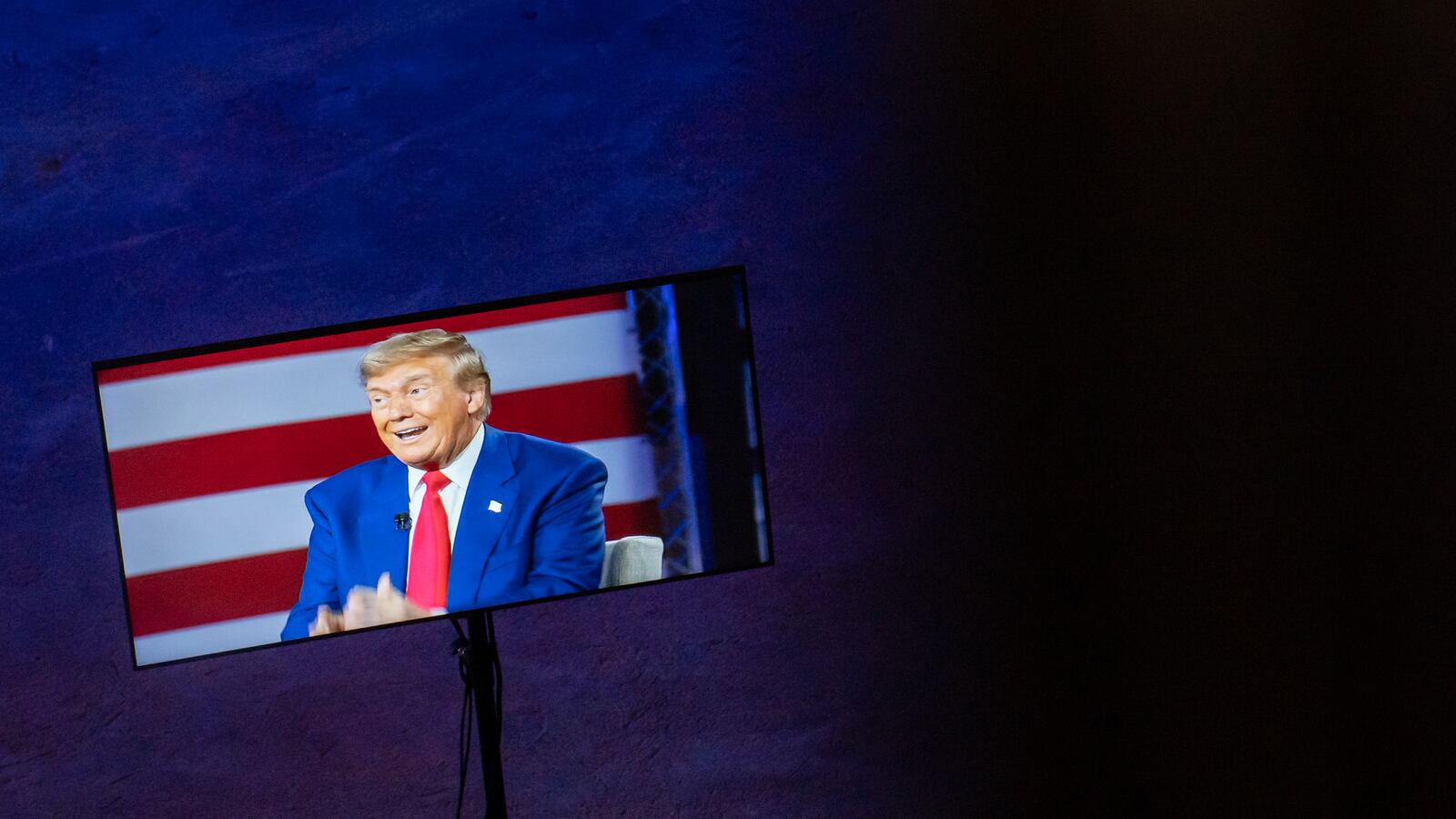

But to answer the question posed by my former student turned elementary school science teacher: There is a need for educators to present “speech related to Trump’s policies or the impact that they may have on our school communities” despite warnings from administrators. It’s probably unhelpful — though hard to resist — to say, “Here’s what I think,” but it’s constructive to discuss differing opinions supported by facts and ethical considerations.

David C. Bloomfield is Professor of Education Leadership, Law and Policy at Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center. A former elementary and middle school teacher, he was General Counsel to the New York City Board of Education.