Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to get essential news about NYC’s public schools delivered to your inbox.

Some New York City students could soon have access to banking services at school, under an initiative announced by Mayor Eric Adams on Thursday.

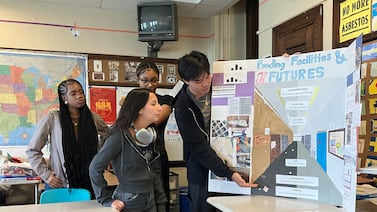

City officials plan to open 15 bank branches directly in public schools, offering students “real world experience opening accounts, saving, and investing,” Adams said during his State of the City address at Harlem’s Apollo Theater. It’s an idea that’s been explored in other parts of the country and the state.

“Interest, credit, and debt will determine our students’ success in the 21st century,” he said. “But too many young people still don’t know what they mean.”

Adams did not provide further details about the specifics or timeline for the program during his speech. Officials from the Department of Consumer and Worker Protection, which oversees the initiative, said the agency was currently working with the city’s Education Department to identify schools that would participate in “the In-School Banking pilot program,” with more details to be announced in the coming months.

The promise was one part of a larger focus on affordability during his annual address, which adopted the theme of making New York City “the best place to raise a family.” The speech, which also saw the mayor lean heavily on issues of public safety and housing, comes at a pivotal moment for Adams as he faces federal corruption charges and a re-election campaign later this year. Adams has pleaded not guilty to the federal charges.

Still, Adams struck a triumphant tone at the outset of his speech, touting investments in public safety, housing, and other city programs. He warned New Yorkers not to “let anyone fool you.”

“Don’t listen to the noise, don’t listen to the rhetoric,” he said. “The state of our city is strong.”

Education was not a centerpiece of his speech, but he tied its importance to the broader themes of his address: He pointed to investments in early childhood education as a means of removing financial burdens from families and to programs that support at-risk youth as a benefit to public safety.

“If we do not educate, we will incarcerate,” Adams said. “The choice is ours to make.”

Adams briefly touted some of the major education initiatives from his administration — like curriculum overhauls for math and literacy — and emphasized the importance of financial education in schools.

He vowed that the city would launch a new program to teach students financial skills at school and place a “financial educator” in each of the city’s 32 school districts. That educator would offer financial workshops, counseling, and curriculum, Adams said.

“We will make sure that every single New York City student can learn how to save and spend money by 2030,” he said. “Today, I’m calling on everyone — our banks, our credit unions, our private sector partners and more — to join us in this course and help set our children up for a lifetime of financial freedom.”

In the fall, the city’s Education Department called on public school families and educators to provide feedback on its K-12 financial literacy curriculum.

Other youth and education-related promises outlined by the mayor during his speech included more free swim lessons for the city’s children, as well as an expansion to the “Fatherhood Initiative,” a program that seeks to help fathers reconnect with their children and develop essential parenting skills.

The speech marked the start of Adams’ fourth year in office and came on the heels of multiple high-profile departures from his administration, including that of former schools Chancellor David Banks, as well as the mayor’s own federal indictment.

“Challenging year, difficult year, and many thought we couldn’t get through it,” Adams said at the close of his State of the City address. “There were some who said, ‘Step down.’ I said, ‘No, I must step up.’”

Despite Adams’ triumphant tone, some critics — and mayoral challengers — were quick to note what was left out of his speech, pointing to a lack of new policy proposals to improve child care access in the city. The issue was a point of tension between advocates and the mayor during budget negotiations last year.

“At the height of an affordability crisis, the Mayor failed to present any concrete plans for child care affordability,” said Rebecca Bailin, executive director of New Yorkers United for Child Care, in a statement. “To make New York City the best place to raise a family, we need bold action — not just words.”

Julian Shen-Berro is a reporter covering New York City. Contact him at jshen-berro@chalkbeat.org.