Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to get essential news about NYC’s public schools delivered to your inbox.

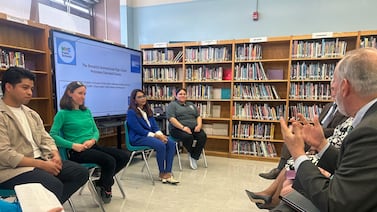

We recorded this bonus episode live at the annual SXSW EDU conference, hosted earlier this month in Austin, Texas. P.S. Weekly’s student reporters spoke on a panel at the event, diving into the pressing inequities of New York City’s school system.

Listen to what it’s really like to navigate the largest school system in the country, from the admission process to stark resource disparities within schools — and what students would change if they were in charge.

Featuring: P.S. Weekly reporters Marcellino Melika, Bernie Carmona, and Salma Baksh, along with Chalkbeat New York reporter Alex Zimmerman.

P.S. Weekly is available on major podcast platforms, including Apple Podcasts and Spotify. Be sure to drop a review in your app or shoot an email to PSWeekly@chalkbeat.org.

P.S. Weekly is a collaboration between Chalkbeat and The Bell, made possible by generous support from The Pinkerton Foundation. P.S. Weekly’s SXSW EDU panel was made possible by generous support from the Siegel Family Endowment.

Listen for new P.S. Weekly episodes Thursdays this spring.

Read the full episode transcript below

Bernie: Hey everyone, it’s Bernie Carmona, and welcome back to P.S. Weekly… the sound of the New York City school system!

I was a reporter during Season One, back when I was a junior at Beacon High School, and now, I’m a senior!

Senior year has been a lot! But I’m so excited to be back on the show! We’re kicking off Season Two with our very first episode. If you’ve been with us since Season One, thank you for sticking around.

P.S. Weekly is a podcast where student reporters dive into the biggest issues facing New York City public schools, but we tell these stories from our point of view.

This season,we’re taking it even further.

But before we get into those stories, we have a special episode for you to kick off the season. Because I and some of my fellow P.S. Weekly reporters from season one were invited to this year’s South by Southwest EDU – for a panel discussion about inequities in New York City’s high school system.

So today, we’re sharing that live recorded panel discussion where you’ll hear from me, Salma Baksh, and Marcellino Melika, — along with Alex Zimmerman, a reporter from Chalkbeat New York.

And we really tackle everything from the complicated high school admissions process to the disparities in resources and opportunities between schools. We’ll share what it’s really like to navigate the largest school system in the country, and what we’d change if we were in charge. Plus, we’ll discuss why student voices need to be part of the conversation when decisions about our education are made.

And this is just the beginning! This season, we’ve got in-depth investigations and conversations about the challenges students, teachers and administrators are facing in this new political climate told by students who know what it’s really like.

So, make sure to subscribe to P.S. Weekly wherever you get your podcasts.

Alright, let’s dive in — here’s our live panel from SXSW EDU!

Salma: Welcome to P.S Weekly. The sound of the New York City school System. My name is Salma Backes and I’m a student reporter with the Bell. We’re super excited to be with you here today for our live recorded episode of P.S. Weekly. P.S. Weekly is a podcast where student reporters explore pressing issues in the New York City school system. It’s a collaboration between the Bell and Chalkbeat New York. The Bell is a nonprofit that is training the next generation of journalists by offering paid reporting, internships and advocating for equitable access to youth journalism opportunities along with P.S Weekly. We also produce the Miseducation podcast and release episodes from our Summer Youth Podcast Academy. Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news organization that covers efforts to improve schools for all students, especially those who have historically lacked access to a quality education. I’m joined today by my fellow student reporters Marcelino Maleka and Berti Carmona, as well as Chalkbeat reporter Alex Zimmerman. Can you guys introduce yourselves as well as the first story you ever reported?

Marcellino: Hi guys. Thank you for joining us. My name is Marcel Maleka. I’m a senior at Francis Lewis High School in Queens, New York. I first joined about the summer after my sophomore year. I’ve also worked for organizations like WNYC through their Radio’s Rookies program. And, of course, my school’s newspaper. Um, my first story was on the imbalance between the boy and girl sports teams at my school.

Bernie: Hi, everyone. Thank you so much for making it. My name is Bernie Carmona. I’m from the Bronx, New York, but I go to high school as a senior at Beacon High School in midtown Manhattan. I’ve been a student reporter with the bill since my sophomore year of high school. But since my junior year, I have also been a student photographer at the Bronx Documentary Center. And the first story I ever reported was about funding inequities in arts education across New York City public schools.

Alex: Hey, everyone. My name is Alex Zimmerman. I’m a reporter at Chalkbeat New York, where I’ve been covering New York City public schools for almost a decade. Before that, I was a reporter at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and the Pittsburgh City Paper, which is the city’s all weekly. I wish I could say that the first story I reported was like an awesome, hard hitting investigation into inequities in public education. But it was actually about. It was actually a profile of a horse breeder in suburban Pittsburgh.

Salma: And back to me. Hi, I’m Salma. I’m a current first year student at Smith College, hoping to study government and sociology. But I recently graduated from Forest Hills High School in Queens, New York. I’ve joined the Bell in my senior year, though I wish I joined earlier. I’ve also reported for city limits through their Clarify internship, and I played a role in restarting my school paper, The Beacon, which is actually what my first story is about. That process of restarting and why the paper left my school in the first place. To start, I would like to engage you guys and poll you on a question. I want you to guess. How many students do you think right now attend New York City public schools? And we have a multiple choice so its easy! This is by a show of hands. I’ll go ABC and D I want you to raise your hand if you think A) 1 million students attend New York City public schools. Whoa. Okay. That’s a lot of you guys. It makes me guys know something. Okay, B) 500,000. No one. Okay. C) 100,000. Also, no one. You guys are really confident on a million or D) 10,000. Okay. Also, no one. So the answer is A, you guys are really smart and I’m thinking you guys are already invested in New York City education, which excites me. 1 million students attend New York City public schools. It is the largest school system in the nation. And if you do the math, that means about one in 340 Americans attend New York City public schools, which is kind of crazy.

Salma: The New York City public school system operates 1,800 schools across all five boroughs the Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan, Queens and Staten Island. And this includes traditional public schools, as well as charter schools. For the 2023 to 2024 school year, 42% of New York City students identified as Hispanic or Latinx, which makes it the largest proportion. This is followed by 20% of students identifying as black, 19% as Asian, and 16% as white. Attending New York City public schools has been a special experience. Taking the subway. Grabbing a bacon, egg and cheese before school. Running to an internship on Wall Street after class. But this hasn’t come without its challenges. For this live recorded episode of P.S. Weekly. We’ll be diving into the inequities that we see in our New York City high schools. We’ll explain the New York City high school– admissions process and how that feeds into a number of other disparities. And then we’ll present solutions. What we would do if we were in positions of power and change things. We’ll follow this up with a bonus segment where will share our school related hot takes and then we’ll have some time for audience Q&A at the end.

Salma: So in order to understand the inequities in New York City high schools, it’s really important to understand how the admissions process works because this is how students are sorted into high schools. To start off, can you tell us about your high school application process Marcel?

Marcellino: For sure. So I attended P.S. 118, which was a middle school in Queens, New York. I want to attend Hunter College High School, but my family couldn’t really afford the fee for their special admissions test. So I was set up to take the specialized high school admissions test, or the SHSAT.

Salma: For members who don’t know what that is. Can you explain the SHSAT?

Marcellino: Definitely. So the SHSAT. is the admissions test to gain entry into these top specialized public schools in New York City. Some of the best public schools in the city and even nationwide. We think about names like Stuyvesant, Bronx Science, Brooklyn Tech, and some kids spent a year preparing for this test. So then it was my turn to take that test and the only really research I had to prepare was this program called Dream? It was a study, a city run unfunded program to help give prep SHSAT. And in hindsight, that program didn’t adequately prepare me for the test. Like we never even took a full practice test to that program, which is, which is crazy. So then it was my time to take the SHSAT. I took it and bombed it. I didn’t make the cut off for any of the specialized schools. And on top of that, I only made my seventh choice high school out of my non specialized choices, Francis Lewis High, which was seven miles away. I’m glad with how things ended up. I love the school. It’s a really big school with a lot of programs and opportunities, so I’m really glad of how things went later on. But in the moment, I was not very happy with how things ended up.

Salma: You say seven miles. Can you tell us how long does that take?

Marcellino: Yeah. So New York City public transit is pretty nice, but um even then I still have to take three buses. It takes me about an hour and a half. I wake up at 4:30 a.m to have like, more than enough time to get ready. So yeah.

Salma: Yeah. I had a similar experience where I also got into my seventh choice of high school and I freaked out. I remember distinctly I was on face time with my best friend and I was crying because I thought I got into a quote on quote bad school. But I also just like you, I found a lot of opportunities at my high school and it turned out okay. Bernie, do you have any thoughts?

Bernie: Well, I–I think I got pretty lucky throughout the process. I ended up getting into my first choice. But I, I specifically remember the stress it took to apply to high schools in seventh grade. Like that’s the year where your grades are the most important. And if you don’t academically excel, then you won’t quote on quote get into a bad school.

Salma: Well, Alex, as a Chalkbeat reporter, you report on the New York City school system every day. Can you tell us a little bit about how the admissions process works?

Alex: Yeah, for sure. I mean, you all probably have just gotten a little bit of a flavor of this, right? Like they’re talking about ranking choices. They’re talking about having to travel long distances in some cases. It is a really, really complex process. So I’m going to do my best to give you just a very high level rundown of how it works. So in most places like where you go to high school is pretty simple. It’s based on where you live, you’re zoned for a school and you go to that school. In New York City, there’s a really unusual degree of school choice. So in theory, students can apply to any high school in the city and there are more than 400 of them. And the way that they get matched to a school is they list in order of preference which high school you want to go to. You used to only be able to list 12 choices. Now you can theoretically list all 400. So again, just really enormous amounts of research that some people put into figuring out which schools to rank. And then once you’ve listed those schools on your application, there’s a really fancy algorithm that someone actually won the Nobel Prize for that matches you with one of those choices. So each student, once that algorithm is rung, gets spit out with one choice that they got matched with. And generally speaking, that’s where students go. The system is really designed to like, open up possibilities for students. So a lot of different schools have like different themes. Some are sort of arts schools, some have more sort of like science offerings, Like there’s just a really diverse set of programs that students can choose from. So if the school that happens to be closest to where you live doesn’t offer that kind of programs you want or you think it just isn’t up to par, like isn’t offering like academics that feel like solid to you. You’re not stuck at that school, like you can apply somewhere else. So the sort of theory behind it is that it opens up, the- creates like a lot of promise for students. But I think as we’re going to talk about in a moment, that system also helps cement inequities. And, and, in some ways it’s a false promise. And we’re going to get into that a little bit. But yeah, that’s sort of like the theory behind the choice system in New York City.

Salma: Right. And to give some context to those inequities, the UCLA Civil Rights Project did a report that found that New York City schools are among the most segregated in the nation. Almost half of New York City public schools are intensely segregated, meaning that 90% or more of their population is black and Hispanic. Meanwhile, half of all white students in the city are concentrated into just 8% of schools. Alex, can you explain the connection between our current admissions process and this segregation?

Alex: Yeah. So one really important piece of that to understand is that there are sort of two main buckets of types of school in New York City. High schools, there are screens, schools that take sort of your prior academic record into account. So these are schools that can look at, you know, your GPA. In some cases, they might require an audition for a smaller subset of screen schools. They can even um like ask you to do supplemental essays or can even ask you to do an interview. And then there’s another group of schools that are predominantly unscreened, which means they’re not taking your prior academic background into account.

For the screen schools, the most important thing by far is your seventh grade GPA and core subjects. So these are students who are like in some cases 12, 13 years old. And, you know, I’d like to throw this back to you all in terms of like what it was like when you were in seventh grade, knowing that if you wanted a shot at a screen school like that was the year that that really mattered for you.

Marcellino: Yeah, for sure. I remember, like, being told back then my teacher is like, oh, like your seventh grade gpa is going to matter. Like, you have to, like, really focus in your classes this year. And I guess I didn’t really, like, internalize that. I felt like those sort of things just told me to just, like, get you to, like, get in shape. Like, sorry about, like, teachers were like, oh, next year, like, the teachers, will be, like, way more strict, like, this behavior isn’t going to fly. And then it’s like the exact opposite. I felt like it was that type of thing where, like, it wasn’t really the truth and um it definitely was. And I think it’s a lot of like pressure to put on like middle school students. You shouldn’t expect them to plan that far ahead, even like planning that far ahead for a thing like college and high school was already like a lot of pressure for a lot of people.

Bernie: Yeah, I agree. I remember specifically internalizing the idea of, of there being good and bad schools. So I began the school I applied to my first choice. There was an essay requirement, and writing that essay was really hard for an eighth grader. Me. But I think at the time I had a lot of teachers telling me that if I didn’t academically excel or didn’t do good during my seventh grade year, that I would end up at the zoned school down the street instead of a good school or a screen school that would offer me these all of these opportunities, you know.

Salma: So we’ve talked about GPA, but I’d like to throw it back to you, Alex, to talk about some other factors that are contributing to segregation.

Alex: Yeah, If you kind of think about seventh grade GPA being kind of the most important thing for getting into screen school is like if you just had like if you just had a regular, like random distribution of students across the spectrum of GPA is then you might expect the screen schools to look pretty similar to the onscreen schools. But of course, that isn’t a random distribution, right? So if you’re looking at like other factors that kind of correlate with a student’s GPA, if you look at like sort of the top echelon of GPAs in New York City public schools and on seventh graders, that is a group of students that is way less likely to be black or Latino, way less likely to be a student with a disability, way less likely to be a student who’s learning English, way less likely to be a student who’s living in temporary housing. So the sort of the way this works in practice is that the screen schools end up draining off a really high percentage of kids who are on grade level and have high GPAs and have are considered proficient in reading and math on the state tests and are end up being schools that are not at all representative of New York City public schools as a whole. And sort of, you know, some of the students here have talked a little bit about like other groups of screen schools in York City. So one of the most famous examples of that are the specialized schools. And they actually don’t really participate in this other kind of like seventh grade GPA process. The admissions to those schools is determined by a single test, which Marcel mentioned a second ago the SHSAT. It truly doesn’t matter how well or poorly you did in seventh grade. For those schools, all that matters is your score on this one exam, and that’s actually like enshrined in state law. And so those schools are even less representative than the other group of screened schools. So you have kind of in New York City, like a few different tiers of screening happening. But in general, what this looks like is the screen schools tend to be much whiter, tend to be much more Asian-American, tend to have more middle class families, and the unscreened schools tend to have more black and Latino kids, more students of disabilities, and just are generally serving like higher need populations.

Salma: I’m wondering, you know, now that we’ve described what screen schools look like, what do onscreen schools look like?

Alex: Yeah. And I think, like, up to this point, we’ve been- I’ve been talking a little bit about kind of like the demographic differences between those schools and sort of like a traditional like racial segregation, economic segregation kind of way. But I think another dimension of that that’s really important to think about is like academic segregation, right? So you’re not just concentrating students of different demographic groups. You’re also concentrating students of different academic abilities at different schools. And so that also has like, like there are screening schools in New York City that are predominantly students of color. And, you know, so it doesn’t totally neatly map on to demographics, but there- in general, like the screen schools are draining off like a lot of the students who are stronger performers academically. And so that also just has like a really profound effect on like what kind of academic programs schools are offering and like what school culture is like. And I want you to just keep a kernel of that idea in your head as we move forward that like we’re when we’re talking about segregation, we’re not just talking about like racial demographics and socioeconomic status. We’re also talking about like what students academic backgrounds look like.

Salma: I’m wondering, have you guys felt the impacts of academic or racial segregation in your high schools?

Bernie: I went to a middle school in the South Bronx, and that school was predominantly Hispanic and black students. And then transitioning from that school to Beacon High School, Beacon High School, 35% white. And when I went into that school, I remember getting the biggest culture shock ever. It was like a shot of imposter syndrome that I had never had before because I was just bombarded with a lot of extracurriculars and a lot of, you know, a lot of options, I’d say options to explore music options, food, sports, film, dance, theater. We had an arts rotation in freshman year that let us explore all of the arts at Beacon High School throughout our freshman year. So I think not having that in middle school really was a stressful move, but I think it introduced me to a lot more opportunities and allowed me to hone in on journalism because that was an issue that I pretty much noticed throughout all my four years.

Marcellino: Yeah, for sure. I remember like in my middle school there was like two Asian people in my like, entire class and then going to my high school. Francis Lewis it’s about 50% Asian. So it was a big demographic difference. And alongside like similar to Bernie’’s story as well, my middle school had no opportunities to be a no extracurriculars or whatever it was just straight up classes. Transition to high school there was always different programs, opportunities and it really like allowed me to like shine as a person. And so I like to go to my, like intellectual curiosity, like, even like within like my personal life as well. Like I joined the Science Research Academy. I’m a public scientist now. I’m doing a lot of different research. I joined the, the string orchestra, and now I play the cello. That’s an instrument I want to keep playing through like college and the rest of my life, and most importantly, I also joined my school’s journalism academy. And that’s like what started all of this for me. So I feel like it was it was a massive contrast, both academically and racially, from middle school to high school.

Salma: So the experiences you guys are talking about reminds me of some reporting that Bernie did actually. And we have a clip of it.

Bernie: Yeah!, During my first year with the Miseducation podcast, I created an episode called The Price of Creativity. And in this short clip, I’m interviewing my friend Kaydee, she’s basically describing what her transition from middle school to high school was like and the differences she noticed in her creative interests.

Kaydee: I did play basketball since that was literally the only sport that my school had, since they didn’t have like much funding and the extracurriculars at my middle school you had to pay to do them. And my family does not have enough money to, like, continuously keep paying for me to do something after school.

Bernie: Those barriers don’t exist at Beacon. Beacon High School program provides access to 96 clubs and 20 PSL sports teams. Beacon’s implementation of a freshman arts rotation allows students to explore multiple electives in a single semester. This gave Kaydee the chance to choose her main elective in 10th grade, which was filmmaking.

Kaydee: It does have like places and teachers that let you, like, dabble into it. You know, like if I wanted to do film as, like my career for my whole lives, Beacon gives me the access to by having, like, film classes, by having like advanced film classes, by having like, teachers who could, like, help me go to, like, good colleges that are, like, made for filmmaking.

Bernie: Yeah. So I definitely feel like Katie’s experience was a shared one. I specifically remember, like during the tour of Beacon High School, we went to the Cellar where our music department is located, and I was just looking at all the ten studios in a row. It’s like they’re ten huge studios and they just have a bunch of audio equipment, Logic Pro X garage band and pianos and guitars. And I was just so invested in, you know, pursuing music and eventually I like started taking the lessons. But I would have never done that if I hadn’t even done the research to apply to Beacon High School. I think going back to Katie’s experience talking to her was, was just so rejuvenating because she had that experience of not going to a school with a lot of opportunities. And despite there being funding for her school, her school, I think, had to use that money to, to support the students in other factors like giving them resources of food and shelter, because Katie’s school was located in an underfunded community and those funds don’t always go towards creative endeavors.

Salma: Hmm. I definitely have noticed something similar with high school journalism opportunities. As ironic as it is for us to be here today, I believe the statistics go that among the 50 highest, 50 high schools with the highest percentage of white students, 76% have a student newspaper. And if you look at the counterpart of the 50 high schools with the highest concentration of black students, that number is only 8%. And it’s a huge, huge gap that advocacy groups have been trying to disrupt. But I think it speaks to the fact that if you go to a wider school, you are getting better opportunities. I can acknowledge the fact that I went to a bigger school and my school newspaper restarted when I got there, but we had thousands of students and that’s what we had the funding to do. Bigger schools, often like Marcel School has what, 5000 students right around that amount, a huge school with a lot of money. And it creates experiences between high schools that are completely different.

Marcellino: Yeah, definitely. Like I remember like my friends who ended up at our zone school, Grover Cleveland, its majority Hispanic. And I remember like talking to them about like our different experiences, like their experiences. And it’s a school that I would have rather not ended up at because of the different opportunities they have compared to Francis Lewis. There, there a lot more lacking and sort of like starting to think about how like different my high school journey would have been if I ended up at my zone school and I didn’t like apply to like literally randomly apply to high schools. Like I remember in middle school, I was so clueless as to what high schools to apply to.

She pulled up the US news site and sorted by high schools, which is crazy because people do that for like colleges, which is very not according to pick. But doing that for high schools is like it’s a bit early to be pulling out. U.S. News. Definitely. But I did that and then she picked schools about like the vibe of their name. So I was like, oh, I’m be a student at Francis Lewis High School. That sounded decent, or I’m be a student at the I.C.E school that sounded like a weird school. I don’t know. So that’s essentially how I picked my high school and sort of like starting to think how, like, I’m sure other people have like, maybe not the same experience, but like similar experiences where, like they were absolutely clueless when picking the high schools. And it really has an impact. You know, like the demographics are there, the opportunities are there, like all the stats show that its a fundamentally different experience if you go to a different school so.

Salma: Alex, you explain a bit more about why these resource disparities exist?

Alex: Yeah, for sure. So there are, as you can imagine, like a lot of different kind of interrelated reasons for this, and I can’t cover all of them, but I’m going to try to do my best to give you sort of the main ones. One is that, you know, if you imagine that there is a group of schools that are basically selecting for families that tend to have more time and resources, like those are families that are also going to be able to exert political pressure in their communities to make sure that their schools have like a wide range of programs and extracurricular activities and sports offerings.

These are also schools that tend to be able to, like, raise more money themselves, right? So they have parent organizations that are raising more money. There are really enormous disparities in PTA fundraising, in some cases between screened and unscreened schools.

If we think about funding more broadly, like how does like city funding go to screen schools compared to unscreened schools? One sort of interesting quirk in New York City’s funding formula is actually that there’s a group of screened schools that get slightly more money, like they get a little bit of a funding boost under the logic that basically they need a little bit of extra money to, to like, well serve accelerated learners and to have kind of programs that will serve students who had been like high performers in middle school is also true that New York City’s funding formula in general is progressive, which means that schools that enroll more high need students generally get more money per student. So if you enroll more students who did not score proficient on state tests, you get a little bit of a funding boost. If you enroll more students with disabilities, you get a funding boost. If you enroll more English language learners, you get a funding boost. But if you consider that, like there are a lot of unscreened schools where there’s really concentrated need, right? Like we had we heard a little bit about this already, but like if you have a school where like a substantial percentage of your population lives in temporary housing, like that school might be funneling more of their resources toward like running a food pantry and partnering with a community organization to provide like laundry services on campus for students who don’t have access to laundry facilities at home. They’re probably devoting more of their resources toward smaller class sizes for students with disabilities. They might be devoting more of their resources to like tutoring to help catch students up. And those are all valuable and like things that I think a lot of principals of unscreened schools are really proud of. But there’s been like a long running debate in New York City about whether that kind of incremental boost that those schools get for their high need populations is actually enough. I’m given the concentrated need at those schools. So even though, like if you just looked on paper like, oh, like, like a lot of the unscreened schools are actually getting more money on a person basis on screen schools, there are big questions about like whether that boost actually accounts for the like deep need that exists on a lot of those campuses.

Another kind of wonky detail that, I that I think is important is New York City, like lots of school districts across the country, saw pretty steep enrollment declines during the pandemic that haven’t rebounded in New York City. The picture is like a little bit complicated because there’s been this large influx of migrant students, but that hasn’t been enough to make up for those enrollment declines. And if you look at like where a lot of those enrollment declines are concentrated, you’ll notice that like unscreened schools tend to be some of the city’s smallest schools too. And because funding is distributed on a per student basis. Right. Like the more students you enroll, the more money you get on. That is also a huge reason why you have like unscreened schools that just like, don’t have enough students at them to justify hiring extra staff or justify having like a full array of sports teams or can pay for afterschool programs. So that’s another sort of dimension of the kind of funding inequity.

Salma: Well, I know you just spoke, but I’m actually going to hand the mic back to you for our next segment. Alex.

Alex: Yeah, so I know we’ve been talking a lot about how the admissions process sort of helps produce some of these inequities in New York City. We have mayoral control of the schools, so we basically have one person right now, Mayor Eric Adams, who really gets to set like education policy. And so I want the three of you to imagine that you are the mayor of New York City. Try to imagine that you’re not under indictment for corruption, but imagine you’re the mayor of New York City. I want, I want you each to sort of talk a little bit about kind of like what your vision would be and and like, what are some things that you think the city could be doing to alleviate some of these inequities? And they don’t just have to be about like the admissions process sort of thinking more broadly about like what changes you would want to see.

Marcellino: Yeah, for sure. So if I was the mayor obviously without the corruption charges, hopefully.

Salma: Hopefully

Marcellino: I would start phasing out screened admissions in New York City hiigh schools. I think the school admissions process right now is sort of incentivize grouping this like collection of like highly funded and like extremely like prestigious programs in a small set of schools rather than focusing on creating quality programs at every school. So every student has what they need to succeed. Obviously, I think phasing out screened admissions is like the, the end to be our solution for the issues that New York City faces. But I think it’s a step in the right direction to make sure that no student is limited from opportunity due to their circumstances.

Bernie: Yeah

Alex: Yeah, yeah. And I’d be really curious too, for, you know, all three of you to kind of weigh in on what it would mean for screening to be like less emphasized. Like what would it have felt like to be in seventh or eighth grade and sort of figuring out like where you would go to high school in a world where, like you weren’t kind of trying to like each of you have kind of described this experience of like trying to vie for what you perceive to be like the schools that would have that would set you up best for college or sort of like have the widest array of programs that you would want in a high school experience. Like, what would it mean for, for like your ability to get that to not be sort of dependent on this kind of sorting mechanism that we’ve been describing?

Bernie: Yeah, I mean, for me, I’m going to keep it 100. I didn’t, I was never taught what a screen or on screen in school was in seventh grade. I, I think it wasn’t until I joined The Bell where I was finally learning about the education system in New York City, and I was learning about the history of Beacon, which was once an unscreened school and had turned screened over the course of five years. And after all of the investments and money that Beacon had, that Beacon had made, they created a brand new building of a $1.5 million dollar school, which was once a simple floor in, at Lincoln Center. And immediately the, the predominantly black and Hispanic student population turned into 35% white. So I think, I think Beacon committed to being a screen school in order to be good. But at the cost of a lot of students losing those opportunities simply for not having access to them. So I think, removing the kind of negative connotation and demonizing what bad and good schools are, are worth exploring. And if I were to go on and say that I were the mayor of New York City, I would, I would specifically integrate programs that are that support those in marginalized communities, specifically student led classes like ethnic studies. Um, my experience with this is that the administration in New York City is very on board with it, but unfortunately it is something that’s optional in some schools and my school was able to happen. But I know that in other schools teachers might not, teachers might recline from teaching that course or there might not be enough students on board with that decision. But where I go to school, the ethnic studies course was brought by student led protests and student activism, which ended up on Chalkbeat News and other news articles on. And as a result of that, a group of students decided to, to commit 4 hours every day, every week to stay after school and develop the course and learn how to approach the topic of race in an ethnically diverse community like Beacon, which is 35% white. But there is that other percentage that has never been taught the concept of race or probably doesn’t know what it is in the context of a school that is predominantly white. So I think having those courses there is really necessary and now that we have tools, my schools, these are digital tools that lets us explore what on the most recent programs that schools are implementing and I think this is a really necessary topic because it’s contributed a lot to my educational experience. I remember being in junior year and having taken US history and ethnic studies at the same time and taking those two courses simultaneously allowed me to become a co facilitator in my senior year. And now I’m teaching my fellow seniors what it’s like to, to explore your racial identity and your cultural identity and how to take action against how to take action against rhetoric that very much exists in our world. I think something the city is doing is implementing those policies. But I think we need a reform that is very concrete.

Alex: Yeah. And one thing I just wanted to kind of add to Bernie’s experience that for those of you who aren’t super with New York City public schools might like fly over your head a little bit is just in terms of curriculum. It has historically been like a little bit of a Wild West where schools just have like a enormous amount of individual autonomy to sort of pick curriculums and sort of see how that plays out. So even though there are sort of some citywide curriculums that are meant to kind of elevate experiences from underrepresented groups, there’s like LGBTQ studies curriculum, there’s like a black studies curriculum, but like what Bernie is talking about at his school is like they actually had to sort of in a grassroots way, kind of like advocate for a class that would like cover some of those topics. And so I just want to like, help help you see sort of like how like the policy suggestion Bernie is making is to sort of like do more to make sure that there’s more consistency across schools in that respect. And he’s kind of working to do that in his individual school.

Marcellino: Yeah, and then to add on as well, my school has usually been a pretty big like proponents of like all of those like good things, all those different types of classes. But even within those classes, they’re not very accessible. It’s like take, even if you do have them, like for example, school offers, AP African-American studies, and the only opportunity to take it is either junior or senior year. In junior year, you have to take U.S. history unless you have that credit from middle school. So you’ll have senior year between AP African-American studies or AP US government and politics. And almost every student is going to choose AP U.S. government. I mean, and it’s very unfortunate because you’re really like asking students to choose between like this, like really essential course that like a lot of people take. It’s only like the core AP classes people take. That’s like almost like critical. It’s like understanding like a civil, your civic duties as like a citizen of this country and like how like everything works over this integral class that teaches things you’ve probably like never like even talked before throughout like much of your educational journey. So I feel like I’m not only like offering the class, but also making it accessible for like more students to take is a big issue as well.

Salma: Yeah, I’ll, I’ll jump in a little. We should be teaching our students about race. I think it’s something that’s coming to light even more with our current administration. And I just hope that New York City makes a commitment to teaching our students about the things that are relevant to them. And speaking of, in high school, I would say one of the things I benefited from was having a very diverse selection of books to read from. I am very fortunate to have gone to a high school that had a robust school library and two wonderful school librarians, Ms.. Clements and Mr. Headgo shout out because, you know, they were my favorite people in high school above my teachers. I would go to Ms.Clements to talk to her about my day, and it’s because I had a school library space that was welcoming, that was inclusive, that had resources that I genuinely needed. And my school library essentially became my safe space, my third space. I make the joke that my school library and my librarians are the reason that I got through junior year because it was extremely stressful. And it’s not even that much of a joke because when I was in that space, I genuinely felt that it was for me and it was a space where I could reset and I could like stop for a minute from all of the seven classes. I wake up at 7 a.m., go to school. Bam, bam, a bunch of classes, more extracurriculars, and this is a spot where I could just go to be myself. And I think it’s a shame that not every student has that opportunity, even though they’re supposed to. I’ll let you know in a little secret that according to New York State law, every single New York City school, with some bureaucratic exceptions, is supposed to have a school library and a school librarian. But this is not the case. There have been Chalkbeat estimates that this is around like 40% of schools have a library and as low as 16% have a librarian. These are shameful numbers, so it’s a shame. I feel that my school library was integral to my high school experience and just middle school and elementary school. And I think every student should have that opportunity. And clearly this is something I’m super invested in. So I have had the opportunity to work with the education chair for New York City Council, shout out Rita Joseph and her chief of staff to work on this issue. But my hope is that everyone recognizes that every student should have a school library and a librarian and hopefully you leave this room knowing that it does have an impact on students, even if they don’t tell you directly. If they come out of that room smiling, it does have an impact on them. Yeah.

Alex: So we’re going to deliver on the last thing that our panel description said we would deliver on, which is a debate. So in New York State and in lots of states and school districts around the country, cellphone bans have been a particularly hot topic in New York. The governor has proposed a ban that would sort of allow school districts to come up with their own kind of policies for forbidding Internet enabled devices during the school day. But I wanted to pose it to the three of you as people who have, like really like recent experiences, you know, being in classes and your schools are kind of have varying policies around this, like give us your hot takes on whether like cellphone bans are a good idea.

Salma: I’m going to start off strong and bold and say that I think I would like to see some form of a cellphone ban in our schools. Granted, this policy is flexible and takes into account the needs of the school. When I think about some of the classes I took in high school, I remember a room where half of the kids are looking down on their phones and, you know, I was that kid. Sometimes I’m not going to lie. If I think that class is boring, I’m going on to my phone. But I think when I think in retrospect of the educational experience that forms for me, it meant that I didn’t feel as engaged in class. When I saw that other students were on their phone, I didn’t feel as interested to learn. I didn’t feel group work was very hard with a bunch of people who were just on their phones. Can I just say that? And I could see the struggle on my teacher’s faces whenever they would ask us to put our phones away and students would still have them. And so I don’t think for the most part that when a student takes out their phone in class, it’s for a reason that’s going to positively impact them. And so for that reason and others, I do believe that we should see some implementation of a phone ban.

Marcellino: Yeah, I definitely disagree. A lot. There’s actually a little bit of bias there, but explain why. So I actually have a very unique perspective on this as my school has not only a cellphone but a total technology ban that isn’t really working out. It’s not really enforced. But anyway, you can’t use your phone in the cafeteria at the library and. You can even have it out in the hallways between classes. If it is seen, it will be confiscated. And on top of that, you can’t use an iPad or a tablet or like a laptop for notes. Like it can’t even be seen or that will also be confiscated, which is insane because it’s really impeded like the the educational workflow for a lot of teachers. I think a lot of people are pushing back heavily on it, especially like a lot of our classes that have like a significant issue with cellphone users and sort of like the big reason why like I have like I’m so strongly against like banning cellphones, completely having this sort of pass because like, it opens the door to more invasive policies, like I mentioned before, like banning like things that are almost like entirely being used for like educational purposes, like, I know barely anyone is actually like using their iPad, like other things, like, besides notes and like, honestly, if you have the time to pull out like Block Blast on your iPad while the teacher is teaching, then it’s probably the teacher’s fault for not teaching enough content. I don’t know. I feel like personally, like there isn’t really like the opportunity to like, use these devices. Especially things like iPads or laptops for like non educational uses and a lot classes cause you actually want to do well in these classes as well. And yeah, this opens the door to more things for, for more things to be taken away if you ban cellphones. On the next thing a lot of those kids that don’t care at all will turn to is their starting to scroll through TikTok, on like their laptop instead for example, and then that’s gonna get banned next, which is taking away a very useful tool for a lot of people. And it’s, it’s a lot of people are pushing back against it. And, you know, in most cases, regardless if a phone is being used, you could just take it away. And I guess that is a form of like a cellphone ban policy but I feel like instituting it like school wide or even like citywide is very like misrepresentative of each individual classroom’s needs and the teacher’s autonomy.

Bernie: I think the experiences are really different from a school that has a cellphone ban compared to one that doesn’t. Beacon has never had a cellphone ban. And I think that’s made our environment a community where, we we’ve learned to, you know, take control of ourselves and, you know, take initiative when we’re using our phones too much, for example. But I think when it gets to the extent that everybody’s using their phone in a class, that’s when I think that a, you know, a restriction should be applied like the cellphone pouches in the entrance of the classroom where students just put their phones there for the period, but they have it for lunch, for example, or free periods. But I’m I think that has made me into a person that’s just relied on my cellphone a lot. I text my friends during lunch saying, Where are you like are you on floor seven or the cafeteria? Like it’s such a convenience for me and it’s become a liability for me. But I was having conversation with Salma, I think over a year ago where we’ve pretty much disagreed on this topic of of having cellphones because I I’ve considered, you know, my school and some students and some of my friends and myself as being, you know, those screenagers that are always on their phones and for social media, for research, for anything, I think technology is something that’s become so, so important to us. It allows us to communicate. It allows us to, you know, advocate. The Bell has an Instagram. We use it for promotions, but we also use it to bring change to our community. So I think it can be used in a lot of good ways, but that’s my hot take on it.

Salma: Well, there’s been no yelling or screaming or name calling in this civil debate. We’re going to have to end it here, unfortunately. But I just want to pause and reflect a little bit and just point out to you guys that when you ask students for their opinions on the policies that are affecting them, they will give you an opinion, They will tell you a lot of things. And that’s something that we have recorded on our podcast is how our students are reacting to the different things that are going on in their school building.

And I think student journalism has been a huge part of all of our lives and has informed the way that we think about our lived experiences. So speaking of that, I want to encourage you all to take your phones out and look up P.S weekly wherever you get your podcasts so that you can keep listening to student voices, because I think that they have a role in educational policy.

CREDITS:

PS Weekly is a collaboration between The Bell and Chalkbeat, made possible by generous support from The Pinkerton Foundation, The Summerfield Foundation, FJC, and Hindenburg Systems.

Special thanks to the Siegel Family Endowment and our friends at South by Southwest EDU.

On this live recorded panel, you heard Salma Baksh, and Marcellino Meilka, Bernie Carmona— along with Alex Zimmerman, a reporter from Chalkbeat New York.

Our executive producer for the show is Ave Carrillo.

Executive editors are Amy Zimmer and Taylor McGraw.

Our engagement editor is Carolina Hidalgo.

Additional production and reporting support was provided by Sabrina DuQuesnay, Mira Gordon, and our friends at Chalkbeat.

Music from Blue Dot Sessions and the jingle you heard at the beginning of this episode was created by the one and only: Erica Huang.

Thanks for tuning in! See you next time!