The moment I had been dreading had arrived. What was usually a mundane part of the day was now a moment of tension.

“Oscar Scr-binder?” the fourth grade substitute teacher’s voice boomed. I heard my friends snickering because she butchered the pronunciation of my last name, Scribner. I felt my face turn scarlet.

“Excuse me, it’s actually pronounced Scribner,” I said softly. I’ll never forget that incredulous look she gave when I, a Korean American, claimed that surname.

“You’re Oscar Scribner?” she asked.

“That’s me,” I gave a wry smile.

This was not a novel phenomenon. If anything, her skepticism seemed like a natural reaction. Scribner was not a Korean name, and it wasn’t even an Asian name. Still, her response cut deep.

I’m not biracial, but my father was adopted by white American parents when he was 3. He ended up with my mother, an immigrant from Korea. So while I am Korean on both sides, in reality, there are probably K-Pop-obsessed Americans who are better versed in Korean than my dad is.

When I was young, I rarely saw my mother’s side of the family, but I spent every winter break with my WASP cousins on a scenic island called Bainbridge, near Seattle. My closer relationship with my father’s family and traditions meant that there were times when I felt like I was white, if only because I had no concept of what it meant to be Korean besides food and my mother’s occasional rants in a language that sounded foreign to me.

I lived in Harlem, a predominantly Black and Latino neighborhood, and I was always among a small number of Asians at the schools I attended. Even though my mother would try to get me involved with the Korean community, she was busy with work, and things like Korean churches were mostly out in Queens. My most Korean experience was going to H Mart, an Asian supermarket chain.

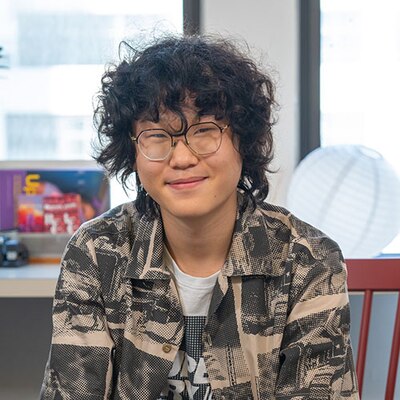

I didn’t conform to Korean standards of beauty since I have curly hair, which is all the rage now with Asian boys, but when I was younger, it just seemed to affirm my detachment from Korean culture.

There were times I felt guilty about my lack of connection to Korea. I rarely saw my maternal grandmother, and the few times I did, my lackluster Korean made me too embarrassed to talk.

My mother and I also struggled to connect. When she was home from work, much of our time together was spent arguing about how I never cleaned my room or about my bad Korean pronunciation. She once spent over an hour lecturing me about my pronunciation of the word “ear” in Korean.

I did love Korean food. I never experienced the banal “Eww, what is that?” reaction in the school cafeteria. But I felt self-conscious enough about bringing pungent-smelling Korean food into school that I decided to suffer through the nasty school lunch instead.

By the end of seventh grade, I couldn’t have been more excited for the start of summer break. Although I made friends, I was socially cooked the whole year. All the little jokes and stares because COVID had originated in China, all the “North or South Korean” questions, all the … whatever, didn’t matter now because I was going to Bainbridge to see my cousins.

As I packed, I heard my mom call out, “Oscar, come sit down!” I rushed out, nearly tripping over the mound of clothes that had accumulated on the floor of my room.

“We’re going to Korea!” she announced.

“Korea!? What about Bainbridge?” This could not be happening. It was a violation of our family tradition; I didn’t care for most traditions, but this was sacrosanct.

“Oscar, we’ve saved up a lot of money for this trip. We go to Seattle every year; don’t you think it’s time we finally go to Korea?” My mom gave me her characteristic assertive smile. “Also, it’s about time we go see your 할머니 (grandmother).”

“Bu-” I stifled my comment after seeing the stern expression on my mother’s face. I wanted to say: “God, why do I have to go to Korea? I don’t want to speak Korean, and … I’ve never been!” But I knew my mother hadn’t been in years, and it felt rude to whine, which she hated, so I nodded my head softly.

When we landed in Seoul, I saw tourists from a wide assortment of countries, wide-eyed and ecstatic. I noticed one family dressed up in BTS shirts. I glared at them scornfully, but I also felt a pang of guilt that they loved Korean culture so much while I wanted to be elsewhere. I remembered my mother’s disappointed expression from all the times I had refused to go to K-Pop concerts or watch K-dramas.

When we walked toward our Airbnb, I noticed how the bright lights of the Seoul skyline seemed to illuminate the sky. There was electricity in the air: People were out enjoying the weekend. It felt odd to be one among many and not the racial outlier I had been for most of my life.

“Wake up, Oscar.” I opened my eyes groggily, my body still sore from our flight.

“What is it, Mom?” I asked in a haze, not wanting to leave the comfort of the bed.

“We’re making 만두 (dumplings).”

“Can’t this wait?” I groaned, rolling around.

“Your 할머니 (grandmother) is here.”

I hastily got up. “지환아!” my grandmother called out to me, and I hugged her.

“Your 할아버지 (grandfather) would be so happy if he could see you here,” my mother sighed. “He looked so much like you!”

Hearing that really hurt; I had never once talked to my Korean grandfather. He passed before I had the chance to go to Korea. Knowing I would never meet him filled my heart with guilt. I felt glad to be in Korea now, to be able to see my 할머니.

For the next few hours, I sat at the table, running my hands through the goopy dough. My shoulders ached from the repetitive action of leaning over the table, rolling out the floury skin, and shaping the dumplings.

“Oscar, what are you doing?” my mother laughed, seeing my misshapen creations. I lifted my head to see the elegant dumplings that my mother and grandmother had made.

At the dinner table, a delicious aroma filled the air. It reminded me of my grandmother’s 떡만두국 (dumpling soup) that she had made the last time she visited us in New York City. Suddenly, all the tedium seemed worth it, and the appearance of my contorted dumplings was secondary.

All year, I had eaten drab ham and cheese sandwiches at school. And now, my eyes watered from the bursts of flavor and from the simple pleasure of eating Korean food unadulterated by other people’s words and stares. I felt a mixture of pride in the food I had made and an appreciation for my Korean culture.

While we were in Korea, my mom took us to a new place every day. She did this with an enthusiasm that I soon began to share. I had grown closer to my mother and grandma in recent weeks, and I was speaking Korean with them.

One day, we were trotting down the narrow streets of Seoul when my mother stopped in front of a gleaming hair salon door. “Let’s go in!” she said.

“What are we doing here?” I asked skeptically,

“You need a Korean haircut,” my mother insisted. She then went to the stylist and whispered in rapid-fire Korean. The stylist nodded. Forty-five minutes later, I stared at my new reflection in the mirror. “What the he-”

“You like it?” my mother gave a light smile.

The reflection showed a bespectacled Korean with artificially straight hair. I felt a semblance of happiness. It was as though I had fully embraced my Koreaness; at the same time, I couldn’t help feeling like the boy in the mirror looked incomplete.

When I came back to America for eighth grade, I began to practice Korean. My mother had quit her job during the pandemic, and we spent more time together and got very close. I made an Asian friend, brought Korean food for lunch, and began to talk about Korean culture openly.

At the same time, my natural curls grew back. During this time, I realized that fragments of my Korean and American identity could coexist.

I set my sights on Stuyvesant, one of New York City’s elite specialized high schools, which is majority Asian and has a large Korean American community. The academics were a draw, but having a chance to make connections with other Korean students was another attraction.

On the first day at Stuy, I was nervous. A raven-haired Asian kid caught my eye outside geometry class. He wore the kind of round, metallic glasses popular among many Koreans, but I didn’t want to make assumptions about his background.

“Hey, what’s your name?” I sputtered out.

I felt a sense of regret as I saw an odd expression on his face.

“Brandon! What’s yours?” he smiled.

“Oscar. Are you Korean?” I asked nervously.

His face lit up. “Korean American,” he said with a laugh, “but, yes.”

The regret washed away, and the conversation became easy.

I’m now a sophomore at Stuyvesant, and during my time there, I have gone on trips with the Korean Student Association and connected with other Korean American students. While we bonded over everything from track meets to late-night study sessions, there was a unique aspect to our friendships. We were all navigating the space between two cultures.

Oscar Scribner is a sophomore at Stuyvesant High School. He enjoys running and reading all things historical.

A version of this piece was originally published in Youth Communication.