Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to get essential news about NYC’s public schools delivered to your inbox.

As a new principal at Brooklyn International High School struggling to get her footing, Kathleen Rucker frequently turned to the school’s recent graduates for guidance and support.

In the decade that followed, those informal conversations evolved into a full-fledged effort to train, develop, and hire the school’s alumni as teachers, paraprofessionals, administrative assistants, and in other roles.

Currently, there are 16 alumni working at the school, and the number has gone as high as 25, Rucker said. The push has changed how Rucker approaches hiring and has paid dividends for the school’s alumni, its staff, and its current students, Rucker said.

“It actually is transformative,” said Rucker. “The school becomes a stronger, more effective curriculum and program, and the alumni are also empowered.”

Now, Education Department officials are hoping that programs like the one at Brooklyn International can serve as a model for the city to creatively address a historic teacher hiring challenge. By cultivating future educators at city high schools and providing non-teaching staff like paraprofessionals more support in making the leap to classroom teaching — approaches often described as a “grow your own” teacher model — city officials hope to build a broader, more sustainable local teacher pipeline.

The push comes as the city expects to hire between 8,000 and 9,000 teachers by next fall — almost double its normal new hire rate — in order to comply with the state’s class size reduction law. The Education Department will have to maintain the heightened hiring levels for years to come as the law takes full effect.

Rucker’s home-grown teaching program got a big boost several years ago when the Education Department rolled out Future Ready NYC — a signature initiative of former schools Chancellor David Banks that provides schools funding and support to help prepare students for career pathways, including education.

With the support of Future Ready and CUNY’s College Now program, Brooklyn International now offers a four-year course sequence to dozens of high school students that gives them the chance to learn about child development, find paid education internships, and graduate with credits they can use toward a CUNY college degree.

There are now 24 schools across the city offering the Future Ready education pathway, reaching an estimated 1,800 students, officials said.

“The Future Ready education pathway is definitely a major piece of the puzzle of how we open up our talent pipeline,” said First Deputy Chancellor Dan Weisberg, whose office oversees the program.

But it’s not just current students that officials are hoping to turn into the next generation of city teachers. Weisberg said the Education Department is also exploring ways to help the more than 23,000 paraprofessionals working in city schools obtain a teaching certificate at “no cost” and in a “relatively short period of time” — though he acknowledged any such changes will ultimately need support from the state and would require partnership with a college or university.

“There should be 5% to 10% of that pool [of paraprofessionals] that are becoming teachers every year,” he said. “That would be a sea change for us.”

‘Alumni in every classroom’

At Brooklyn International, school leaders recognized the value of cultivating future educators long before the Education Department launched its citywide initiative.

Students rarely enter the school with an explicit interest in education, but often form close relationships with staff and over time grow interested in doing the kind of work from which they benefited so much as students, alumni and staffers said.

“I went from, ‘I don’t want to go to school,’ to, ‘I want to become a teacher in a school,’” said Anunna Meem, a 2016 alum who now works at Brooklyn International as a history teacher.

Alumni staffers bring a unique ability to relate to students’ experiences and pick up on subtle signs from kids that other educators might miss, teachers and administrators said.

Erin Fleischauser, an 18-year veteran teacher at Brooklyn International who did not attend the school, said working alongside one of her former students as a co-teacher was eye-opening.

“I’m paying attention to how kids connect differently with him than they connect with me, and I’m noticing little moves that he makes that open up opportunities that I didn’t do,” Fleischauser said.

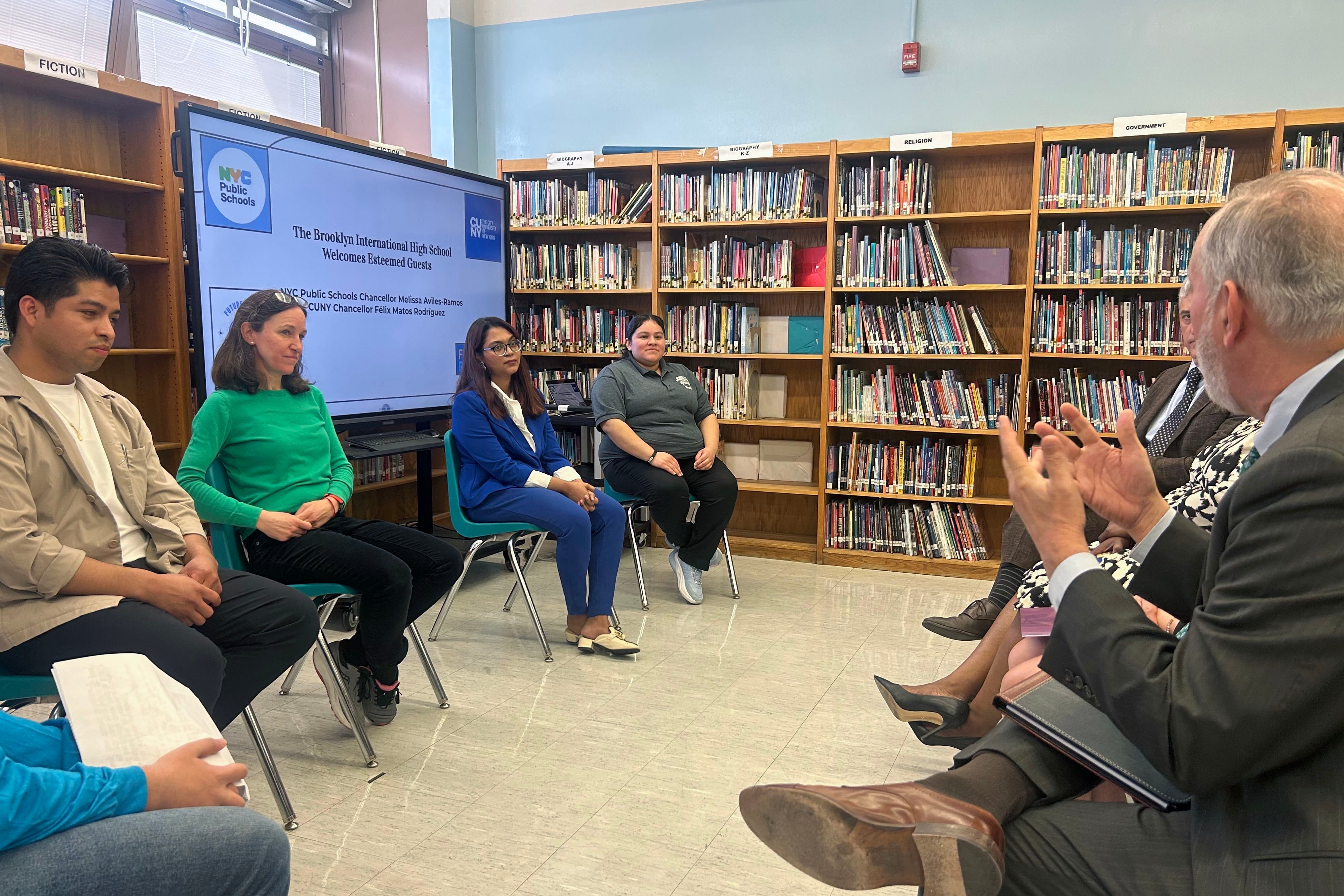

Schools Chancellor Melissa Aviles-Ramos, who visited Brooklyn International on Tuesday to learn about the teacher preparation program, pointed out that recruiting future educators from international schools could also make a dent in the city’s longstanding shortage of bilingual teachers.

One Brooklyn International alum, now an education researcher, is doing research for her dissertation on the benefits of hiring alumni as teachers, and has found that it can increase students’ sense of belonging and connection in school, Rucker said.

For Rucker, the ultimate vision is having “an alumni in every classroom.”

Obstacles to teaching careers persist

Even with support from programs like Future Ready, there are still formidable obstacles standing in the paths of many prospective educators.

Meem, the Brooklyn International alum-turned-teacher, noted that many of her classmates pursuing a teaching degree at CUNY’s Brooklyn College struggled with the requirement to complete unpaid student teaching hours — facing pressure to earn money while they worked toward a degree.

And while the city’s in-house teacher preparation work offers promise, it’s a long-term investment at a time when the city’s hiring needs are immediate. That’s why Weisberg believes strengthening the paraprofessional-to-teacher pipeline can provide an immediate shot in the arm.

Paraprofessionals as a group are more reflective of the city’s student demographics than teachers, are more likely to live in the communities where they work, and often have deep experience supporting students with disabilities — another perpetual shortage area for city teachers.

Teachers earn roughly twice the starting salary of paraprofessionals, but the cost and burden of pursuing a certification keeps many paraprofessionals from making the leap, Weisberg contended. He argued that paraprofessionals should have a way to convert their work experience into credit toward a teacher certification, noting that “nothing predicts your future effectiveness as a teacher better than your current effectiveness as a teacher.”

Michael Elsen-Rooney is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Michael at melsen-rooney@chalkbeat.org