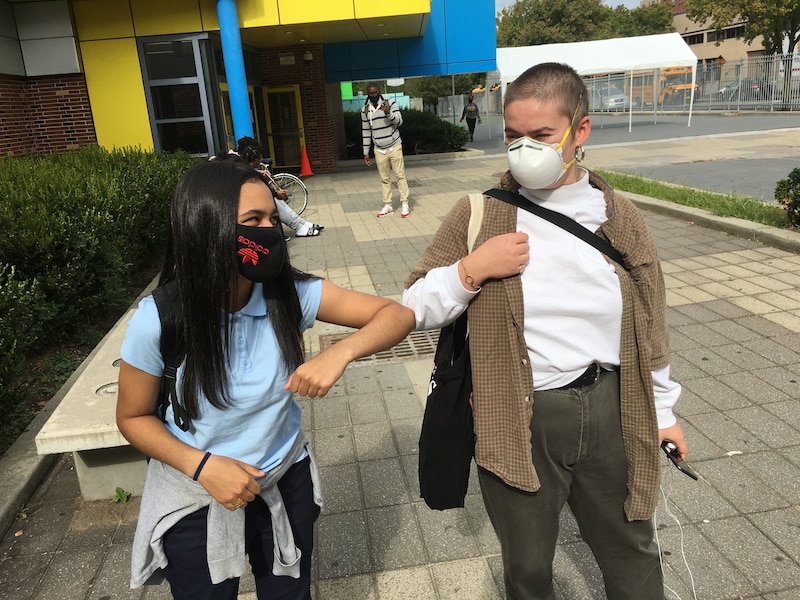

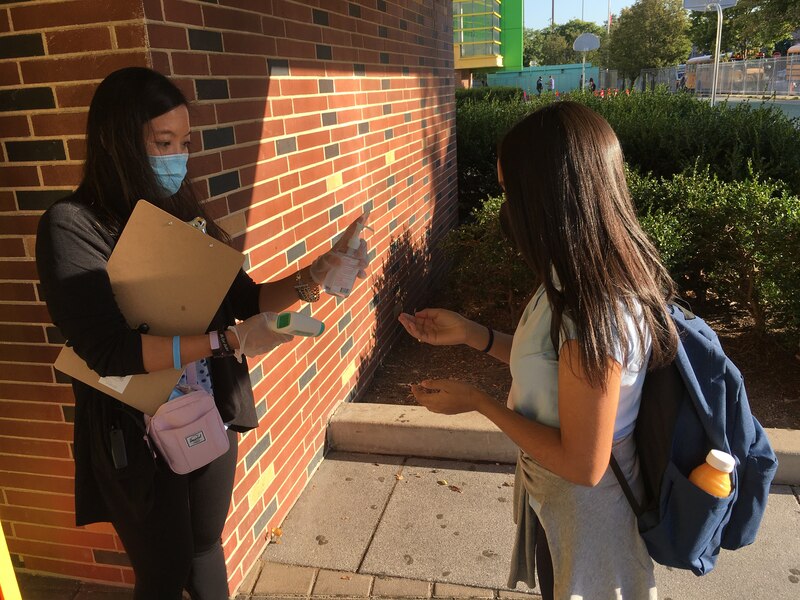

With a squirt of hand sanitizer, a temperature reading, and an acknowledgement that she has no coronavirus symptoms, Ashanty Peralta does something she hasn’t been able to do in six months: walk into a school building.

Ashanty has been anticipating her first day of in-person classes as a high school freshman for weeks. But as she enters her Bronx school a few minutes before class starts, there’s no need to jostle for a desk and no chance to catch up with other students about the summer.

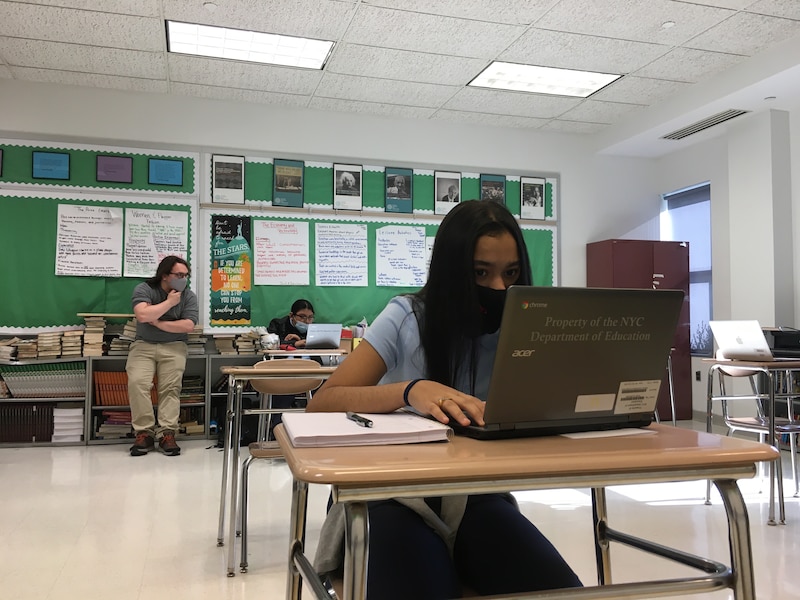

She is the only student in the room.

For the next four and a half hours, Ashanty is joined by just one other student, who arrives a few minutes late and picks a desk several feet behind her.

While half of New York City’s roughly 1 million students have opted for fully remote learning, Ashanty is one of hundreds of thousands of others who returned to their classrooms over the last two weeks — part of a bumpy and high-stakes effort to reopen the nation’s largest school district. After a summer of being locked down in her two-bedroom Bronx apartment with her mom, stepdad, and two younger brothers, Ashanty was glad to be back at the Urban Assembly School for Applied Math and Science, also known as AMS, which she has attended since the sixth grade.

“When I’m in school I feel more motivated,” said the 14-year-old who immigrated from the Dominican Republic five years ago.

Still, the normal rhythms of catching up in the hallway or in the cafeteria have been upended. Ashanty can expect to spend four straight classes in Room 24, with the teachers coming in and out rather than the students. Lunch is afterward.

Huge uncertainties remain about whether in-person learning will continue without disruption. The city recently shut down 124 district schools after infection rates surged in parts of Brooklyn and Queens — less than a week after all grades returned to their classrooms.

No Bronx schools were part of this latest wave of shutdowns, but the borough was the hardest hit when the coronavirus first exploded in New York City, with Bronx residents twice as likely to die from COVID-19 than in other parts of the city during the peak of the pandemic.

The virus has particularly ravaged Ashanty’s part of the borough, which is adjacent to a heavily polluted roadway, and it has disproportionately affected people of color. At AMS, where 98% of students are Black or Hispanic, dozens of students and staff have lost loved ones to the coronavirus, including Ashanty, who lost a great-uncle and a cousin.

But even if AMS is never forced to close due to the virus, Ashanty’s time in the building will be limited: Due to space constraints and restrictions on the number of students who are allowed inside classrooms, she will only attend classes in person five days a month.

She’s determined to make the most of them.

When school buildings were forced to shut down in March, Ashanty’s school swept into action, quickly supplying her with a laptop and an internet hotspot the school purchased through a crowdfunding campaign — a task that took many other schools several weeks or even months.

Her school did not provide much live instruction in the spring. Instead, teachers relied heavily on pre-recorded videos and assignments students could complete on their own time. Ashanty appreciated the flexibility to do her work when she could, especially as she adjusted to online learning and occasionally helped her 12-year-old brother decipher his assignments. Her current remote schedule on the days she’s at home is more demanding than the spring, with more live classes, leaving her feeling overwhelmed with her workload.

Her mother, a teacher before the family immigrated from the Dominican Republic, has worked long hours as a cashier at a grocery store throughout the pandemic. Her stepdad, who works in food service, saw much of his company’s business dry up, though it is slowly picking up again.

Lingering concerns about the pandemic and mistrust of the city’s safety promises have contributed to fear of returning to classrooms. At AMS, about 60% of the students opted for fully remote learning, above the citywide rate of 50%.

Ashanty is nervous about starting high school in person, but she has been craving the chance to make the short walk to AMS from her red-brick apartment building perched above the Cross Bronx Expressway. She wants to ask her teachers questions when they pop into her head rather than dashing off an email and waiting for a response. She is eager to look in the school’s library for a graphic novel instead of relying on her teachers for assigned reading. She’s excited to see her friends.

“There are so many things you can do in person that you can’t do online,” Ashanty said.

So Ashanty is thrilled to be in the same room as Mateo Portune, her energetic first period physics teacher. The class has already met virtually, but confusion over her schedule and oversleeping meant Ashanty had already missed some of the online class. She was quick to make up the work.

Portune begins with a question meant to provoke debate: Is water wet?

Usually the topic commands the attention of a full classroom of students. But, for the first few minutes, Ashanty is the only student in the room, and the conversation is solely between her and her teacher.

“This will be a very weird first period if no one else shows up,” Portune jokes. “You can call it ‘Ashanty’s physics class.’”

Even after Ashanty’s classmate, Chris, arrives a few minutes later, the two students quickly decide that water isn’t wet. The point isn’t to reach an answer, though. It’s to learn how to evaluate the sources of scientific claims. (Portune says there isn’t an agreed-upon answer, and he doesn’t tell the students one.)

To keep the conversation going, Portune begins peppering them with rapid-fire questions. Ashanty, who is shy, is relieved when the debate fizzles out after a few minutes, and Portune moves on to a set of assignments students can complete independently with occasional check-ins.

“I felt a little bit uncomfortable or awkward,” Ashanty said later. “It was like, ‘share, share, share.’”

Educators across the city are still getting the hang of socially distanced teaching and this is Portune’s first time with students in a physical classroom since March. He said the water debate was more successful online because there were more students who could piggyback on each other’s arguments and debate with each other. But online classes come with big pitfalls, too. Ashanty, like other students, is reluctant to turn on her camera even though she enjoys interacting with her teachers.

Now, Portune is headed back to the drawing board to make sure students in his in-person classes don’t feel like they’re constantly under the spotlight and forced to participate — an overwhelming experience for many ninth graders.

“The content is going to stay the same but the lessons are going to need to be tooled a little bit,” Portune said. “I can’t plan as if it’s a regular classroom.”

Ashanty looked forward to her Algebra class all morning.

When she arrived in the United States five years ago from the Dominican Republic, Ashanty didn’t feel like she had been well prepared in math. But Ashanty is drawn to topics she finds difficult, and her interest in math has blossomed.

“There are some students who math comes to very easily,” said Hannah Hogness, Ashanty’s eighth-grade math teacher. “And there are some students where math is a struggle but they really enjoy that learning process, and that is Ashanty.”

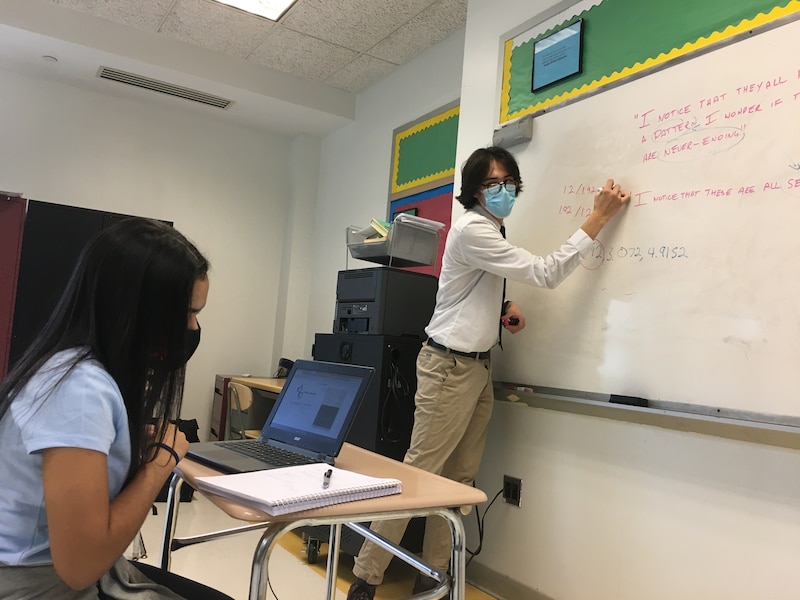

Ashanty’s second-period math class is focused on geometric sequences, a set of numbers that are governed by a fixed growth factor. The teacher, Austin Ha, spends the first few minutes of class guiding students through various sequences, such as 40, 120, 360, 1080, 3240. (The growth factor in that case is 3.)

Then he sets Ashanty and Chris to work independently on a new problem: What’s the growth factor of ripping a piece of paper in two then stacking them and ripping them apart again repeatedly? At first, Ashanty struggles to wrap her head around the problem. But Ha takes notice and helps her set up a table to represent the number of pieces of paper remaining after each rip to get her thinking about the growth rate. In a couple minutes, it clicks.

“Yes!” Ashanty whispers to herself as she figures out the growth factor is 2 and punches the answers into her laptop. At the end of the period, Ha offers a bonus problem for her to work on.

To Ashanty, these moments feel like switches going off in her head — and are why she came to school in person. It is hard to have so few classmates, but with no disruptions from other students she has her teachers’ undivided focus.

“There isn’t that specific moment where it’s like ‘yes, you have all my attention’” with virtual learning, Ashanty said. “I like how my teachers are pushing me and are giving me support they wouldn’t give me online.”

For the first time in more than four hours, Ashanty leaves Room 24. She hasn’t removed her mask, gone to the bathroom, or had more than a snack since she left her apartment. Aside from two “brain breaks” to stretch, she has hardly left her desk.

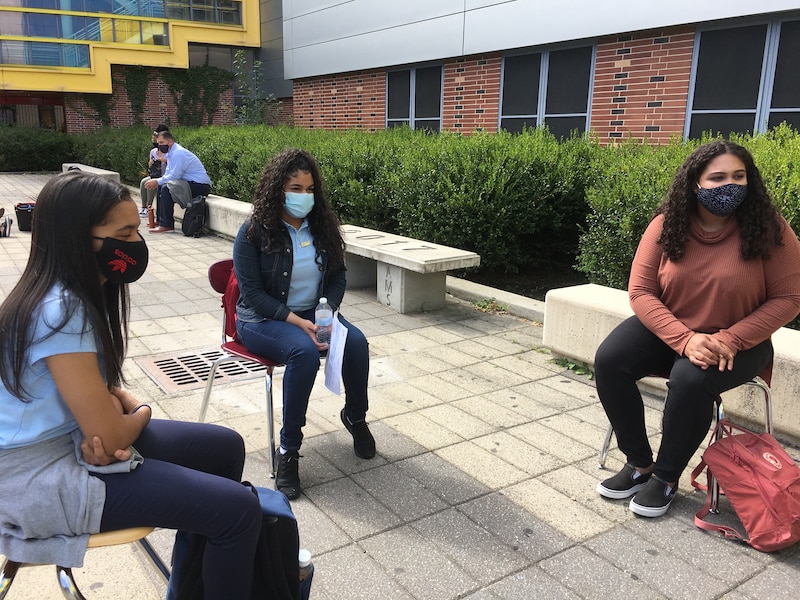

The last activity of the day is a simultaneous advisory group meeting and lunch, and it’s the first time she’s seeing other students besides Chris. The school cafeteria has mostly been emptied of tables and chairs, and it’s a nice day, so the group drags a few chairs outside to the courtyard at the front of the building.

In the six months since New York City became the epicenter of the nation’s coronavirus pandemic, this is the most socializing Ashanty has done — and it’s a big reason she wants to be back on campus. Other than occasional picnics with her family, she hasn’t left her apartment much. She loves playing tennis, but she and her brother have only been allowed to play once.

Only two other students in her 15-person advisory group attend school in person on Ashanty’s first day. She’s excited one of her friends from middle school is in the same group.

For a moment, Hogness, Ashanty’s favorite teacher from middle school, drops by to say hello, and Ashanty’s eyes light up. Before the school shutdown, Ashanty was an eager participant in lunch sessions Hogness held in her classroom where students could talk about whatever was on their mind.

Those meetings fueled Ashanty’s interest in social justice, which has opened her eyes to everything from transgender rights to aspects of her own school’s culture she wants to change. In one instance, Ashanty raised questions about the school’s discipline policies and why students don’t have more of a direct role in resolving conflict before a detention is issued.

“I want to share all of these things that I feel about a topic and sometimes it doesn’t come up in class,” Ashanty said. “You can talk to [Hogness] about Black Lives Matter or the LGBTQ community and what is happening.”

But even as Ashanty relishes these moments catching up with her friend and teacher, there are constant reminders that this school year will be like none other.

In the last few minutes before dismissal, principal Ingrid Chung begins handing out thermometers for at-home temperature checks before arrival and consent forms for the city’s random coronavirus testing program.

Ashanty is exhausted and is just now finishing a cream cheese sandwich she picked up from the bodega on her walk to school. There isn’t much doubt in her mind that she wants to return for the next day of in-person classes. Mostly, she’s disappointed it won’t come for another week.