This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

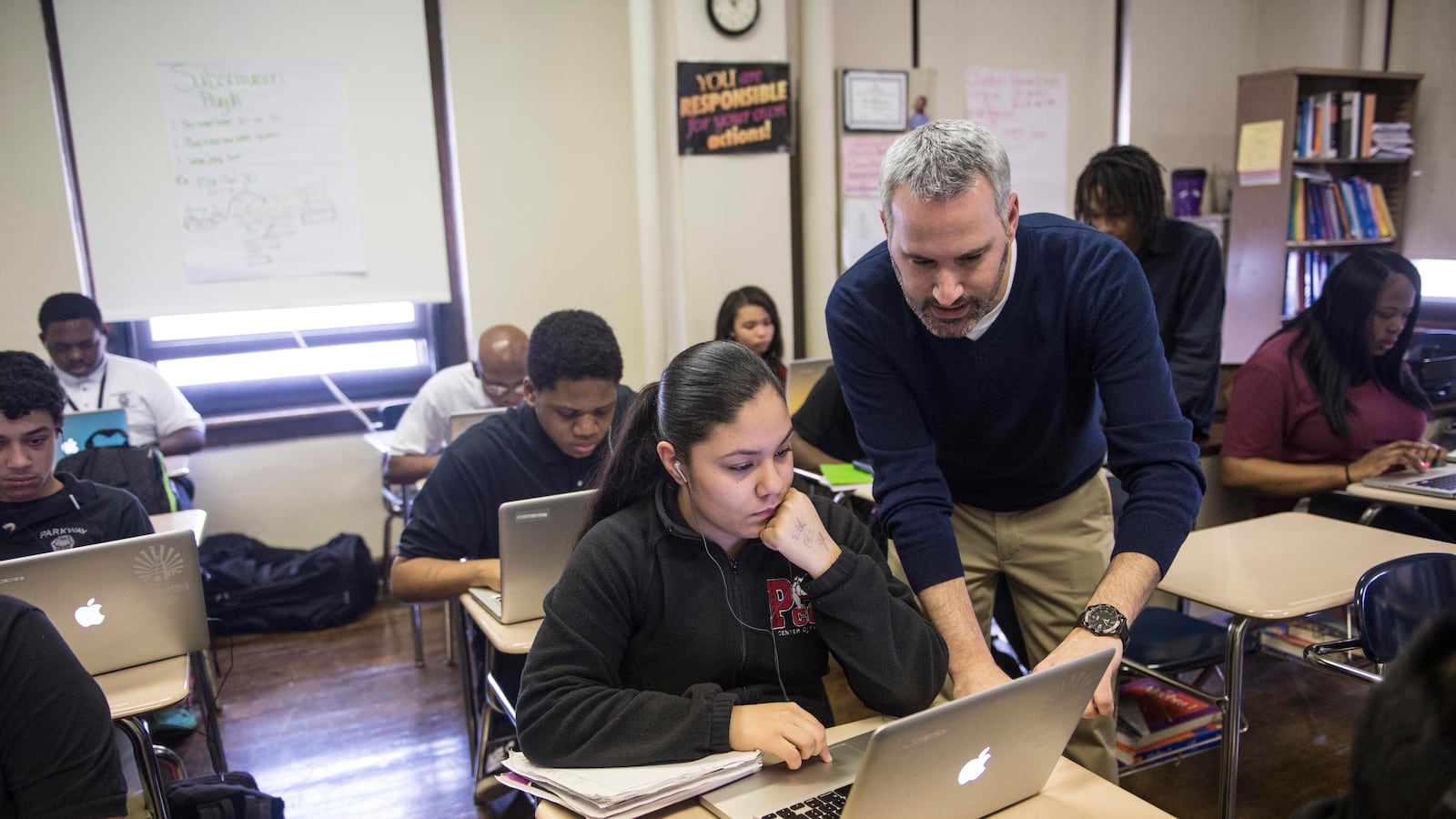

At the start of class, 9th grader William Cook has logged on to an academic website, just as his algebra teacher, Robert Mastrangelo, instructed.

“Do the reading and watch some of the videos before you do the practice,” advises Mastrangelo, who moves down an aisle to assist a student having trouble logging on.

Cook settles back into his chair, does the reading, and clicks on the video, which shows multiple equations on a chalkboard and how to use one equation to solve another. The website, CK-12, provides free open-source content and technology tools for classrooms. Like his classmates, Cook is using a MacBook Pro from a mobile laptop cart to access the site.

This is not new material. Mastrangelo, math chair at Parkway Center City High School, teaches the subject the standard way, using an algebra book and a white board, as well as his instructional skills.

But students need practice to learn math, and they get a lot of practice and extra instruction at Internet sites selected by the teacher.

Mastrangelo said that CK-12 is a new website selected because the programming is high-quality and it’s free – an important consideration for districts dealing with tight budgets.

“The video goes step-by-step, showing exactly what you need to do if you’re having a hard time,” said Cook.

“There are practice problems. Sometimes the goal is to get 10 right, so you keep working at it until you get the answers.”

This combination of classroom instruction and online skill-building is called blended learning, an approach that has been in development since the 1990s. Now that nearly every Philadelphia school is wired, blended learning is rapidly gaining advocates for its capacity to personalize instruction. Where adequate technology is present, it’s actually happening.

Students who need extra time and practice can get that kind of remedial help. Other students can move forward at a quicker pace as they acquire skills.

Then there’s the simple fact that kids seem to love it.

Students access programs on computers in their classroom or in a computer lab, on laptops at home or via their cellphones. The fact that cellphones are seemingly ubiquitous among older students, even among youth in poverty, has changed the ballgame, said Karren Dunkley, Parkway Center City principal. Classroom Internet service is not essential because students use cellphone data plans to connect instead.

“We always think of access to technology as being an issue – the digital divide. But a lot of our scholars have these different apps on their phones. … They’re digital natives,” Dunkley said.

She said that “for the most part,” students do not use cellphones during the school day. They download apps that they use to complete assignments. Students lacking smartphones can use the Internet in the library after school.

At other city schools, blended learning initiatives may be stalled because of outdated computers, slow Internet connections, or policies that treat cellphones as distractions rather than potential learning tools. Those issues were cited by respondents in a recent Notebook survey about the technology situations at schools.

Trying various programs

For the District, cost is a consideration, but numerous programs are available for free or at relatively low cost. Schools are trying various programs, and District officials are watching the types of programming being developed at three new high schools, the LINC, the U School, and Building 21.

In addition, the District opened Philadelphia Virtual Academy, a cyber school, in 2013, but that model falls within the definition of blended learning only when students regularly spend time face-to-face with an instructor.

“We’re trying to instill hands-on, face-to-face meetings and also just trying to get some student engagement with the teachers and teaching assistants,” said Philadelphia Virtual Academy principal Dave Anderson.

“The blended learning initiative that the District is actually undertaking, we’re way on the outside of that. We’re full-time, solid virtual.”

Fran Newberg, deputy chief for educational technology for the District, said programming typically “is based on school need and the school improvement plan.” Principals and teachers are getting professional development on the ways that blended learning can be used, and a list of recommended materials is being compiled by subject matter and grade level, she said.

In the lower grades, teachers often use what is called the rotation model, where some students work on math or early reading skills at computer stations while the teacher delivers instruction to a larger group of students.

“Early literacy teachers are naturals at this type of model because they’ve always organized their classrooms in flexible groups … and in learning centers,” said Newberg. The idea, she added, is to find ways to differentiate instruction.

Early on, skeptics questioned whether online programs were a ploy to displace teachers, but Newberg challenged that view.

“I would say very strongly that teachers stay front and center and are very needed to provide guidance, feedback, and facilitation both in the rotation model and the a la carte model.”

In the a la carte model, a student takes most classes at school but may take one – either for credit recovery or an Advanced Placement (AP) course – online. Newberg said the District “is exploring the possibility” of bringing back online AP courses, which were offered in District high schools for several years through an outside company.

In any model, Dunkley emphasized the role of a teacher as central.

“That technology without a teacher who’s able to provide each scholar with targeted individual feedback really doesn’t work,” she said.

Engagement = learning

Blended learning has come into its own at MaST Community Charter School in Northeast Philadelphia, according to CEO John Swoyer. He named a half- dozen programs his teachers use – including Study Island, Reading Eggs, Storia, Lego robotics products, and a site called Code.org, which teaches young children coding basics.

Stirring student interest, even excitement, is a consideration for using blended learning tools.

“We try to make the space as engaging as possible, and we also try to use technology [that way]. If you’re engaged, you’re learning,” said Swoyer.

Students are almost blasé about the trend their teachers are embracing. Cook, for instance, is a longtime user of computerized instruction, including Study Island, a skill-building program, and First in Math, which gives children math practice geared to their knowledge level.

The First in Math curriculum supplement has been in Philadelphia schools for more than a decade and now can be found in 87 public schools and 67 Archdiocesan schools, according to Nan Ronis from Suntex International of Easton, Pa., the developer of the program.

The program treats math practice as a game, and students “seek out time to play on their own,” building skills in the process, Ronis said.

Students can practice addition and subtraction or algebraic equations. The maker of First in Math also distributes the 24 Game, which has thousands of school-aged fans. Cook said that he played and competed at a regional event when he attended Richard Allen Preparatory Charter.

“Even when I was a kid, I loved math,” he said.

Shawn Henderson, one of Cook’s classmates, said that the CK-12 site is very helpful, “especially when I can’t reach my teacher. And it challenges you with each question. It’s a good way for children my age to practice between classes and when we’re not in school.”

Another classmate, Gayle Centeno, admitted to “struggling through algebra a lot.” Her family has a computer, but she logs on to practice on her cellphone.

“They have a mobile version, so that’s what I use,” she said.

According to Mastrangelo, students seeking to boost their grade from the previous quarter use Study Island to “remind themselves” of course material, as do algebra students prepping for the Keystone exams scheduled for May. The programs allow the teacher to monitor each student’s progress.

“I can see exactly what they can and can’t do,” he said.

In the end, Mastrangelo said, the online programs are supplemental to instruction in the classroom.

“You still need to teach.”