This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

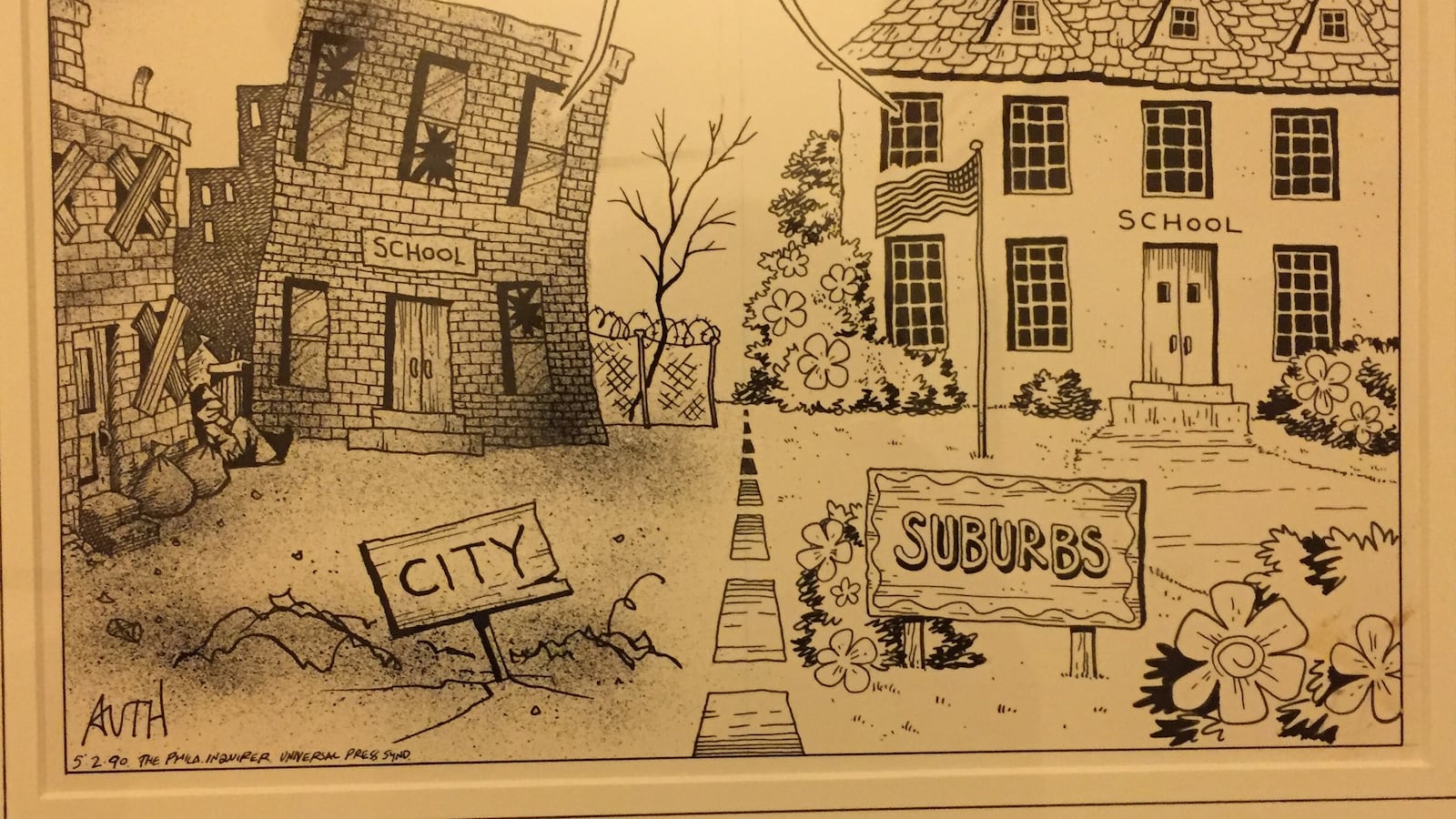

A new national study puts Pennsylvania among the most educationally segregated states in the country, with borders that create wealthy, predominantly white school districts right next door to those that are mostly nonwhite and impoverished.

The study, called Fault Lines, was done by the nonprofit group EdBuild. It examined more than 33,500 borders and compared the child poverty rates of neighboring districts. The analysis showed that Pennsylvania has six of what it called the 50 “most segregating borders” in the country, with the widest gaps in poverty rates. It ranked behind only Ohio with nine and Alabama with seven. New York also has six.

The current system of paying for schools largely through local property taxes “gives the incentive for high-value communities to self-segregate and to draw school district borders narrowly and draw lines to keep low-value areas from diluting the tax base,” said Zahava Stadler, EdBuild’s director of policy and research.

With 500 school districts, most with enrollment of only a few thousand students, Pennsylvania is an example of that practice. It is also one of 23 states that have a regressive school funding system – one that directs fewer dollars to needier students and more dollars to wealthier ones. The spending gaps between wealthy and poor districts in Pennsylvania are the widest, on average, of any state in the country.

The new school funding formula adopted by the state legislature earlier this year is not likely to change that pattern anytime soon, because it applies only to new dollars, not to the total amount of state aid sent to a district. For more than two decades, Pennsylvania had no predictable funding formula, allowing inequities to grow. It gave districts the same amount they got the previous year, regardless of enrollment drops or other changes, and doled out increases based on politics rather than need.

In the United States, education is decided locally, paid for primarily through the property tax. State school aid is designed to compensate for differences in local taxing capacity and property wealth. Although poorer districts in Pennsylvania get more from the state than wealthier ones, it is not enough to make up for the vast disparities.

Pennsylvania not only has especially segregating borders, but it also has been stingy with the total amount of state aid it distributes compared to other states, contributing just more than a third of total spending compared to the national average of around 50 percent.

“When state funding is tenuous, as it has been over and over in Pennsylvania, it disadvantages low-income districts more than high-income districts,” Stadler said. “And getting any formula in Pennsylvania has been like pulling teeth, for sure."

The study said that 26 million children across the country live in high-poverty districts.

“There is no doubt that low-income students are harmed by a system of borders that effectively quarantine them into underserved districts,” the study said. “… America has permitted our schools to become a system anathema to our ideals, funding education in a manner that prevents a vast number of students from accessing an equal start in life.”

The most segregating border in Pennsylvania – and the third worst in the country – is between Clairton and West Jefferson Hills in Allegheny County, two districts just outside Pittsburgh, where the gap in poverty rates is 41 percentage points. Clairton, with a child poverty rate of 48 percent, is an old steel town that took a huge hit from the demise of that industry and the nation’s general economic downturn.

Last year, during the state funding impasse, Clairton was considering a shutdown due to lack of sufficient revenue. Meanwhile, neighboring West Jefferson Hills was modernizing its high school, Stadler said.

In the past, Clairton has sought to merge with other districts to shore up the funding base for its schools, but there were no takers.

Others among the most segregating borders in the commonwealth involve Reading, which also has a child poverty rate of 48 percent. The poverty rates come from U.S. Census Bureau figures and are for 2014. Poverty is defined as annual income of just under $25,000 for a family of four.

Philadelphia’s child poverty rate is 36 percent, so the differences between the city and its suburban districts aren’t as enormous as those, but they are still quite large.

Philadelphia has 13 border districts, compared to five for the average U.S. district. In the case of five of its contiguous districts – Haverford, Springfield (Montgomery County), Lower Moreland, Lower Merion, and Neshaminy – the difference in child poverty rate exceeds 30 percentage points.

Eight of the city’s border districts have poverty rates under 10 percent.

The city of Erie, where the child poverty rate is 34 percent, also borders districts that are much better off. Superintendent Jay Badams has been outspoken about the injustice of huge funding disparities among districts, and has invited controversy by saying that he has contemplated shutting down the city’s high schools and sending students to these districts as a way to improve their opportunities.

The study laments that there is no mechanism to re-evaluate district borders, unlike congressional districts, “which the law recognizes must be amended to keep up with growing and shifting populations in order to maintain a fair and democratic society. Because our schools are treated differently, districts have not been evaluated in generations, and those that find their population or wealth dwindling are left with nowhere to turn.”

Stadler said that there is a growing body of research showing that all students do better in socioeconomically and racially integrated school districts. But such research is not heeded in policy, she said.

Instead, we have created a “circularity problem,” she said, in which families who have the means move to better-off districts, further concentrating wealth – and, on the other end, concentrating poverty, which creates huge impediments to building and maintaining high-achieving schools.

Such a counterproductive result was almost assured by a 1974 U.S. Supreme Court ruling called Milliken v. Bradley that arguably has had more of an influence on educational equity than the much more famous Brown v. Board of Education decision of 1954 that outlawed school segregation written in law.

In a 5-4 decision in the Milliken case, involving Detroit and its suburbs, the court ruled that school desegregation could not be enforced across school district boundaries, which “significantly diminished the capacity of courts and governments to integrate schools and cleared the way for district borders to be used as lawful tools of segregation.”

Stadler said that other research has found that racial segregation among districts is declining, but income segregation is increasing, a phenomenon driven almost entirely by families with children moving in search of better schools – a way of life ratified by the Milliken decision.

Today, the single most “segregating border” in the country is between Detroit and Grosse Point, Mich. Half of Detroit’s children live in poverty, compared to just one in 15 in Grosse Point.

Discussing policy solutions, Stadler said that district consolidation, advocated by some, is “politically challenging.” But, she said, “It is possible to have school dollars cross district lines without sacrificing local governance.” She cited Vermont, which imposes a statewide property tax that is pooled at the state level and redistributed to districts.

Besides comparing child poverty rates, the EdBuild study looks at property values, median household income, the per-pupil amount for schools raised by local taxes, and the amount of state aid for each district. Its full data set is accessible on its website.

It used U.S. Census Bureau and National Center for Education Statistics data for 2013 and 2014. There are 13,590 school districts in the country. It did not include rural districts in the analysis.

New Jersey has three of the 50 most segregating borders, including the one between Camden and Haddon Township. New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie has advocated a plan to change how state aid is distributed to give every district an equal amount per pupil, regardless of a district’s wealth or poverty, a system that would divert millions of dollars from poorer districts to wealthier ones. He argues that the poorer districts have not made good use of the funds they receive, adopting the viewpoint that “money doesn’t matter” in producing educational results. Stadler said that most research shows that this is not the case.

EdBuild is a nonprofit founded in 2014 to focus on the issues of school funding and equity. Although backed by some of the same players who have invested in school choice and charters, it has focused its research on how the practice of funding schools locally exacerbates inequality and stifles opportunity for the nation’s poorest students.

“As an organization, EdBuild doesn’t discuss teacher policy and the focus is not on school choice and charter policy," Stadler said. “Ultimately the majority of students attend traditional public schools, and the equity issues in traditional public schools will affect more students than any discussion of choice. We are thinking about how to improve the lot of more children. This is where our focus is.”

Greg Windle

Greg Windle