This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

Child advocates are asking the Philadelphia School District to immediately ban suspensions of first through fifth graders and provide more support to schools as they work to shift disciplinary policies away from punishment and toward positive behavior supports. Suspensions of kindergarten students were banned last August for most infractions, but not for offenses that cause "serious bodily injury."

In a letter to Superintendent William Hite and the School Reform Commission, the advocates cited an alarming number of suspensions meted out to students in the fifth grade and below, plus federal data showing that black students are punished at rates far disproportionate to their white peers and students with disabilities at greater rates than those in regular education — trends also prevalent nationwide.

"This is appalling and unacceptable," the letter said. It was signed by a coalition of groups including the Education Law Center-PA, One Pennsylvania, ACLU of Pennsylvania, Youth United for Change, as well as Councilwoman Helen Gym, and others.

Karyn Lynch, the District’s Chief of Student Support Services, said in an interview that the District agrees with the goals of the letter, but that effectively implementing such a major policy change takes time. Extending the expulsion ban to grade five is a goal and is under active consideration, she said, but can’t be done instantaneously.

"We are putting in place supports and preparing our school staff to operate in a different way," Lynch said. "We are changing our culture, and a change in our culture doesn’t happen overnight."

Teachers and other staff who deal daily with students need to be thoroughly prepared and trained, she said, adding that the District is acutely aware that "you can’t suspend your way to better behavior."

The advocates say that despite the policy change, kindergarten students are still being suspended this year — 58 as of February, according to the Education Law Center — with many schools using a broad definition of "serious bodily injury."

Lynch could not confirm that number, but said that no sweeping policy change would be 100 percent effective immediately. She added that 58 would be a major advance given that, according to state data, 615 kindergarten students were suspended in the year before the policy change.

"The step we made last year was a big step for us, and it’s been relatively successful," she said. "It takes a good deal of work and effort and I think we’re accomplishing a lot."

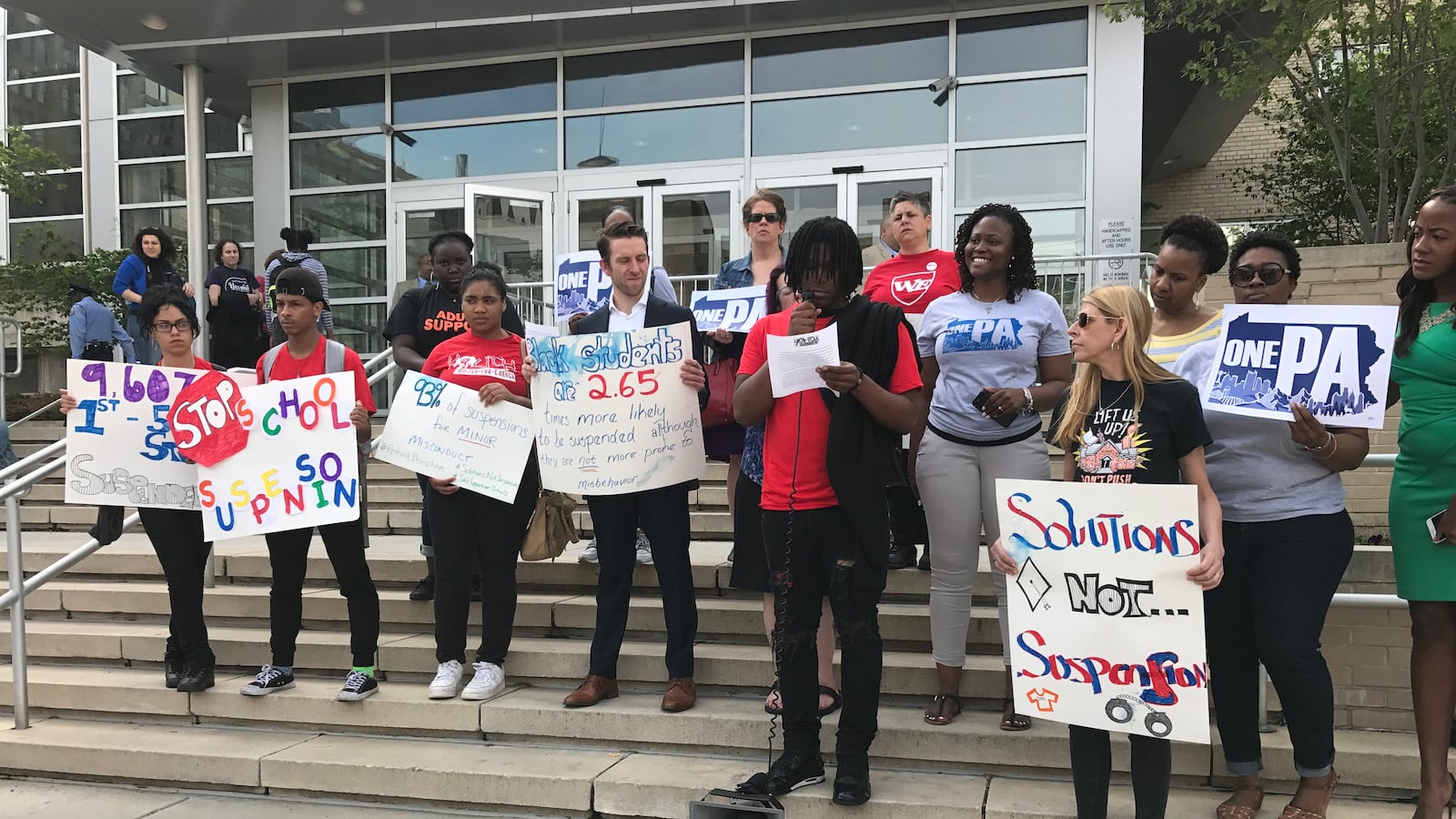

At a rally ouside District headquarters before the SRC meeting, ELC attorney Alex Dutton said the advocates demand that the District establish a plan to expunge the education records of any kindergarteners improperly suspended this year "so as not to cause them further harm." They also want "targeted support" for schools that registered five or more kindergarten suspensions.

"These suspensions are harming the District’s youngest learners," said Dutton. "Suspensions set students on a path toward future discipline, truancy, and school dropout, all of which feed the proverbial school-to-prison pipeline. That this is happening to black students and students with disabilities the moment they walk into the schoolhouse door is a true injustice."

High numbers of suspensions were handed out to first through fifth graders in the District last year, according to the latest Pennsylvania Department of Education’s Safe Schools Report: 1,081 to first graders, 1,779 to second graders, 2,192 to third graders, 2,295 to fourth graders, and 2,260 to fifth.

As a comparison, there were just under 12,000 first graders in District schools in the fall of this school year. Assuming similar enrollment numbers for last year, that means nine suspensions were handed out per 100 1st graders. The percentage of individual students suspended is likely lower because some are suspended multiple times.

But the numbers go up to 15 percent suspensions per 100 students in second grade, almost 19 per hundred in third grade, 20 in fourth grade, and nearly 22 in fifth grade.

Dutton said that ELC had determined that "over 93 percent of these suspensions were for subjective ‘conduct’ offenses…that did not involve violence or drugs." Assuming that the suspension was for one day, that is a collective loss of 10,000 days of instruction for students in the fifth grade and below, crucial time because those are the years in which students are learning to read. Data show that students who don’t read proficiently by third grade are much less likely to have successful school careers and graduate.

Over the last few years the District has amended the student Code of Conduct to eliminate suspension generally as a penalty for such infractions as loitering, not wearing a uniform, violating the dress code, keeping one’s hat on in class, and truancy.

Citing the Civil Rights Data Collection in the U.S. Department of Education, the advocates’ letter said that in Philadelphia black students are 2.65 times as likely to be suspended once, and 3.08 times more likely to be suspended more than once, than their white peers, "even though black students are not more prone to misbehavior," citing research on the subject. Those numbers were for 2013, the latest year available.

Lynch said that District officials have been "closely watching" the issue of racial disparities in discipline and participated in several programs over the past several years on the topic with the Obama White House.

For several years the District has been making an effort to move away from "zero tolerance" policies that emphasize punishment, and is working on prevention, "restorative practices," and providing more support for students, including mental health and other services. It has also embarked on an project to train teachers and counselors in "trauma informed" education techniques to de-escalate student stress before it erupts into bad behavior.

"We are creating environments where teachers, principals, supportive staff within schools, climate managers, counselors, and other individuals interacting with students have the skill set and knowledge to negotiate the conflicts that naturally occur in a schoolhouse," she said.

"The same time you’re changing your discipline practices you have to increase knowledge, provide professional development, help people better understand the trauma children have experienced that contribute to their behavior and the inability to self-regulate. There’s a balance you have to reach."

Some of the programs the District has implemented include circles where high school students can talk out their differences, Positive Behavior Intervention and Supports (PBIS) in K-8 schools, and a program called Second Step in the lower grades to help children with social emotional learning. More schools are opting to hire climate managers and the District is increasing the number of counselors, she said.

In a statement, District spokesman Lee Whack said overall suspension rates are declining, which "demonstrates our commitment to reducing suspensions while improving the environment and safety in our schools. Our goal is to increase the time a student spends in school, because the more time a student spends in school the greater the likelihood they will read on grade level, graduate, and be prepared for college, career, and life."

At the rally, speakers reiterated that suspension from school is destructive, especially for young children. A statement was read for parent Stephanie Greene describing what happened to her 7-year-old son.

"I will never forget the day my eldest son received his first suspension," she said. "He was 7 years old and it was Valentine’s Day. After handing out Valentines Day cards to his entire class – as several other students did that day as well – my son decided to give another student a special gift. He spent his allowance money that morning at the dollar store to buy a young lady a necklace and earrings. He was suspended for sexual misconduct…That day my son was labeled as a problem student. The suspensions continued, growing in number every year, he missed so much valuable class time that it was impossible to catch up."

The suspensions had an economic impact on the entire family, the statement said, and she refuses to send her younger son, who is four, to "a district that values him so little that instead of creating solutions they elect to push out students."

Suspension may seem like an easy solution for teachers who are trying to reduce disruption, make students accountable for bad behavior, and create an environment where other students can learn. But it is ineffective and ultimately counterproductive, said Kristin Luebbert, a teacher at Bache-Martin school who spoke as a member of the Caucus of Working Educators, a group within the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers. The PFT itself did not sign on to the advocates’ statement.

Luebbert spoke at the rally and elaborated in an interview.

Over her 16 years in the District, "I’ve come to an evolution of thought," on discipline, Luebbert said. "It’s easy to get behind a ‘no excuses’ attitude, but when you start getting to know the kids and families, you realize it doesn’t work. You can’t suspend your way to success. Besides all the moral and ethical issues, which are legion, it just doesn’t work, if you want to be super practical about it."

The student comes back to school angry and stressed about falling behind in their work. The parents are angry because they may have had to miss work to stay home with the child, "so they don’t come in for a meeting with teachers in a receptive mode" to talk about the child’s problems and how to correct them. Younger students in particular aren’t likely to "come back with the attitude that I understand what I did wrong, I’ll do better. The message they get is that mom is angry because I did something that made things wrong at home, so their default response is to be angry, so that doesn’t help whatever the original challenge is."

Luebbert has taken the trauma-informed classes offered by the District and gives them high marks, but said they fill up quickly and don’t often fit into the schedules of teachers who have children at home or other obligations. Teachers also take them on their own time.

Pamela Harbin, who is from Philadelphia but now lives in Pittsburgh, is a co-founder of the statewide Education Rights Network, which is working to break the school-to-prison pipeline and promote equity for students with disabilities.

"All over Pennsylvania, parents are building a movement called ‘Solutions, not suspensions,’ to end the overuse and disproportionate use of suspensions and expulsions," she said. That includes advocacy with legislators and local policymakers.

Councilwoman Blondell Reynolds Brown is introducing a resolution in Council asking the District to ban suspensions up to the 5th grade.

Students also spoke. "Children between the ages of 5 to 9 shouldn’t be suspended before they even know the difference between right and wrong," said Nasir Lee, a member of Youth United for Change.

Lynch said that the District and the advocates have the same goals: "We’re each trying to do the same thing with our kids."