This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

For about an hour Wednesday morning, Ricki Straff and about 20 of her fellow teachers went to Hawaii.

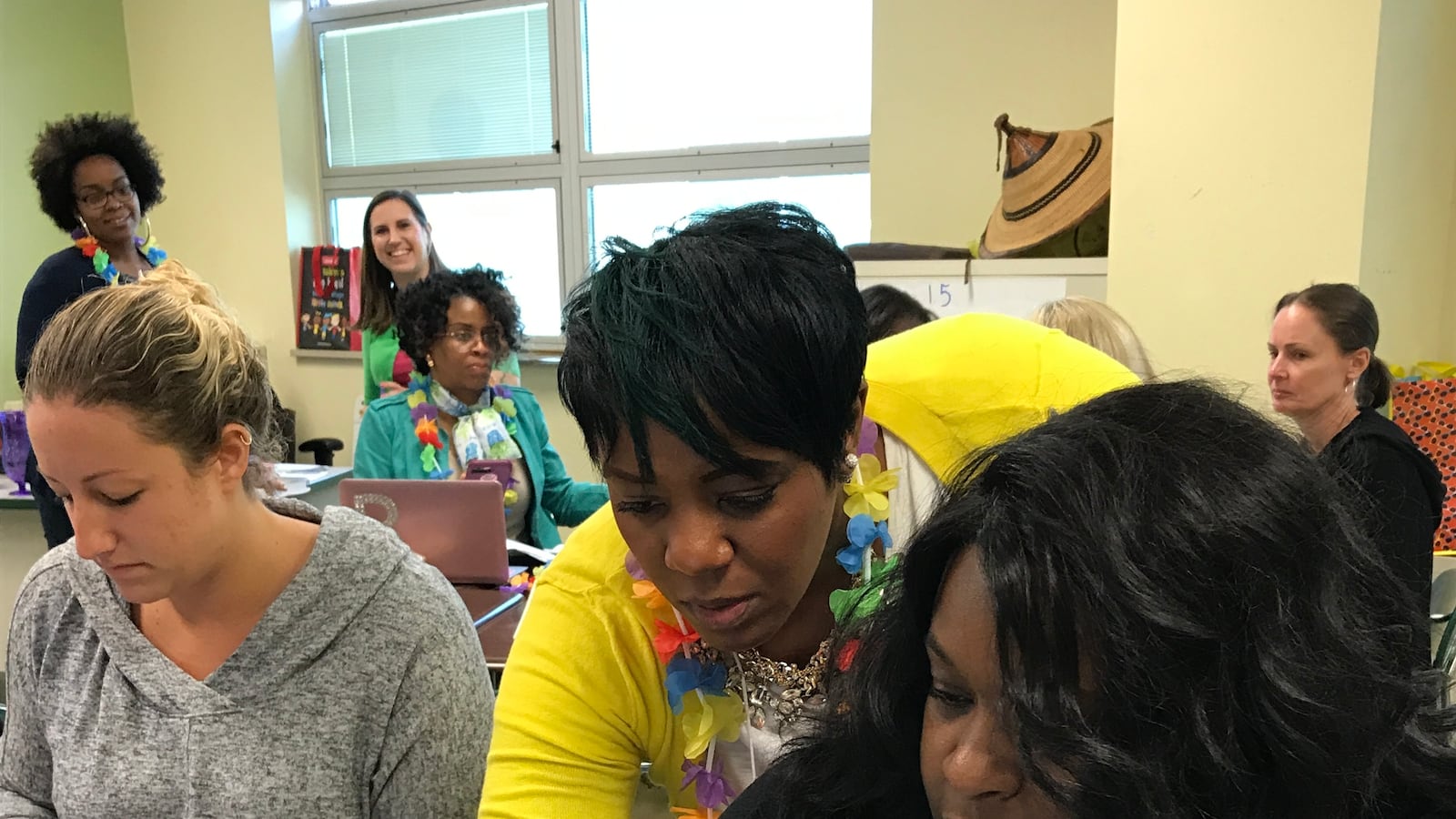

Well, not exactly. They were in Classroom A125 at Fels High School in the Northeast, attending the District’s third annual Early Literacy Summer Institute. And the leaders of a session on “Writing Objectives and Lesson Planning Using the Curriculum Engine” thought it needed something to spruce up what sounded like a dry and technical exercise.

So there were beach balls and paper leis, bells and recorded hula music.

“Well, it’s summer, and we’re in a vacation mindset,” explained Brenee’ Waters, who led the session with Ginger Smith. “And we wanted people to be more receptive to what we’re telling them.”

That’s because the mission of the summer institute is serious – teaching young children to read fluently by the end of 3rd grade, a benchmark that predicts with sobering accuracy a child’s future life chances. For instance, students who miss that milestone are four times more likely to drop out of high school, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

Waters and Smith are school-based literacy coaches, and the “students” were all kindergarten through 3rd-grade teachers.

For Straff, a 28-year District veteran who has seen everything, the professional development offered by the Institute “is one of the most informational offered to teachers. It really breaks down the whole literacy framework.”

Teaching young children to read is difficult, requiring broad skills, knowledge of many strategies, and the ability to diagnose a child’s learning style and reading impediments and to adjust instruction on the fly.

“Many people underestimate how complicated it is,” said Diane Castelbuono, the District’s deputy chief for early childhood education. Especially in a city like Philadelphia, “where you have a classroom of 30 kids, some learning-disabled, some English language learners, some who just struggle with the basic foundations. Teaching in that environment is not easy, and we are hoping to provide our teachers with evidence-based tools that can help them.”

The week-long institute is run by the District’s Office of Early Childhood Education and the Office of Curriculum, Instruction, and Assessment, with money contributed by the Fund for the School District of Philadelphia and the Lenfest and William Penn Foundations. For the third consecutive year, it was held during the week after school closed for the summer. Partners include the Children’s Literacy Initiative, which pioneered many of these techniques and has been working in Philadelphia for more than two decades to help teachers fill their classrooms with words, books, and writing. CLI has received major grants from the U.S. Department of Education to scale up its work.

In 2015, teachers from 40 schools were trained. Last year, they came from 53 schools, and this year, more than 850 teachers from 57 schools signed up. All the District’s schools with early grades are now covered.

The teachers are paid for their time, but the institute is voluntary. Eighty-five percent of the eligible teachers signed up, Castelbuono said. Once each school’s teachers participate, the school gets “leveled libraries” for K-3 classrooms to use in instruction. Books are coded based on difficulty, and students know what level they are on and can pick appropriate books, which motivates them to read and to improve.

Session topics included creating a literacy-rich environment, early literacy for students with disabilities, developing writers, using data to inform instruction, and working with English learners.

“Teaching reading is a very individualized process. Each child learns at a different speed and progresses at a different pace,” said Castelbuono.

Straff, who most recently taught 2nd grade and has spent 25 years at Andrew Hamilton Elementary in West Philadelphia, is about to transition to being a literacy coach herself.

“This is giving me information I can take back to my teachers,” she said. Her main takeaway: The training “will make you a better teacher, but you have to pick and choose what will work for you and your students.”

That is the daunting task facing Elizabeth Picarella, a newly minted graduate of Temple University with a degree in early childhood and in special education who is about to embark on her first job at one of the District’s most impoverished schools, Meade Elementary in North Philadelphia.

“So far, as a new teacher, this has been phenomenal,” she said of the institute. “It’s great to talk to veteran teachers, to hear from experts, to see what really works and learn the research behind it, and be shown examples of how you can implement the best strategies.”

Especially helpful to her? A practical session on how to keep other students productively occupied when a teacher is running “guided reading” for a group that needs extra help. “In order to get the most out of that time, you need other students to be working on things that are beneficial to them,” she said.

The other session that stood out for her was a session on developing writers. The instructor, she said, was “so enthusiastic about writing. She’s in love with her students and the work that she does. She had handouts, examples of student work, things I can use in the classroom. As a new teacher, it’s great to get anything.”

Another relatively new teacher, Anna Phelan, said that she found the sessions invaluable, also stressing their practicality. Phelan did her undergraduate work at the University of Scranton and got a master’s degree as a reading specialist from St. Joseph’s University. She taught two years at a Catholic school in Olney and will start teaching kindergarten at Overbrook Educational Center in September.

“One thing that sets this institute apart – it’s not only theory, but also practical implementation and what exactly you can do to improve literacy in the classroom,” she said. “As important as theory is, like learning why students should read independently, as a teacher, you are looking for real solid practical ways to take that theory and put it into practice. What has been so incredible about the last three days is how much practical advice we are getting about what we can do.”

In a session on developing writers, she asked about how to know when students were ready to revise their work or were still in the drafting stage. “Multiple teachers said, this is what I do, one shared her rubric with me. There’s a real culture of sharing ideas and brainstorming, and it’s so incredibly helpful.”

The session run by Waters and Smith was not so much about modeling particular classroom strategies as it was to help teachers understand how to use the “curriculum engine” on SchoolNet, the District’s online platform. The District uses several different reading series, and this tool helps teachers match the books and the lessons with specific state standards and learning goals.

“It’s not online lesson plans; it’s more like resources so you can make your lesson plans,” said Waters. “It’s how to access resources for literacy in your particular grade.”

Learning how to use it effectively can save teachers time and give them different ideas for approaching instruction so the two-hour literacy blocks don’t become repetitive and boring. It also helps teachers integrate literacy-building exercises and strategies into social studies, science, and math lessons.

The institute attendees start each day hearing a keynote speech from a nationally-known speaker on literacy topics, including Pedro Noguera, who specializes in how schools are influenced by social and economic conditions. Karen Mapp, a lecturer at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, will speak Friday on family engagement.

Superintendent William Hite stopped by the institute on Wednesday morning to visit sessions and talk with teachers.

“This is important work for us, our signature initiative,” Hite said. “If we get children reading on grade level by 3rd grade, we solve a lot of other problems.”