This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

No cyber charter school in Pennsylvania have ever received a passing academic score from the state, and very few have come close, according to information recently highlighted in a report from the office of Democratic State Rep. James Roebuck of Philadelphia.

Roebuck and other House Democrats have assembled a package of bills that would further regulate charters by reforming how they use reserve funds, rules for leasing buildings, special education payments, contracting, the teacher evaluation system, disclosure in advertising, school building closures, and the transfer of school records. The package would not single out cybers, but other legislation has been introduced that would reduce their per-student reimbursement.

Pennsylvania has 13 cyber charters enrolling more than 34,000 students, or 10 percent of all the cyber students in the country.

These schools are authorized not by local districts, but by the Pennsylvania Department of Education. But districts must send per-pupil payments to cyber charters for each local student they enroll, and the payments are the same as for brick-and-mortar charters, even though cybers have fewer expenses.

This has proven frustrating not only to the districts and other proponents of traditional public schools, but to several groups that favor school choice and charters.

In 2016, the National Association of Charter School Authorizers and the national charter lobbying group 50CAN released a report on cyber charters, which found that compared to traditional public school students, full-time cyber students have poor academic growth. Overall, cyber students make no significant gains in math and less than half the gains in reading compared to their peers in traditional public schools, this report found.

Pennsylvania is among the “big three” cyber charter states, along with California and Ohio. Collectively, they enroll more than half of the country’s full-time cyber charter students.

Timothy Eller, a former press secretary for the Pennsylvania Department of Education during the administration of Republican Gov. Tom Corbett, registered as a lobbyist in 2015 and formed the Keystone Alliance for Public Charter Schools. The alliance advocates for brick-and-mortar charters but does not allow membership for cyber charter schools.

It’s been a difficult school year for many U.S. cybers. Ohio’s largest chain was forced to close mid-year, and others closed down in Georgia, Indiana, Nevada, and New Mexico. In the past, it has been rare for states to close cyber charters despite low achievement across the sector and several financial scandals.

Pennsylvania was not part of this wave of closures, though it does have cybers with poor academic records and at least one major financial scandal.

Of the 43 states that allow charter schools, only 35 allow cyber charters. The eight that do not are Delaware, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Tennessee, and Virginia. Only 23 of the states that allow cybers have actually authorized any, according to the report from the National Association of Charter School Authorizers. Those states plus Washington D.C. have a total of 135 full-time cyber charter schools.

Cybers make up just 2 percent of all charters in the country.

At its peak, Pennsylvania had 14 cyber charters, more than 10 percent of the nation’s total. However, Education Plus Cyber closed in December 2015 during the state budget crisis after its bank pulled the school’s line of credit. Some staff also alleged financial mismanagement.

Education Plus is one of five cybers in Pennsylvania that have closed over the years. In 2013, after just one year in operation, Solomon Cyber announced it would have to close at the end of the school year. Einstein Cyber, the state’s first and at one time its largest cyber charter, closed in 2003 after a litany of problems from financial mismanagement to inadequate services for special education students and a failure to supply computers to all students.

The 2016 report by the national charter authorizing group and 50CAN found that 70 percent of cyber charters are run by for-profit management companies, while only 15 percent of brick-and-mortar charters are run by for-profit companies. And the cyber charters serve significantly more white students and fewer Latino students than traditional public schools throughout the country.

The report also found that the typical cyber student stays for two years and that students who leave are dramatically more likely to transfer schools again afterward.

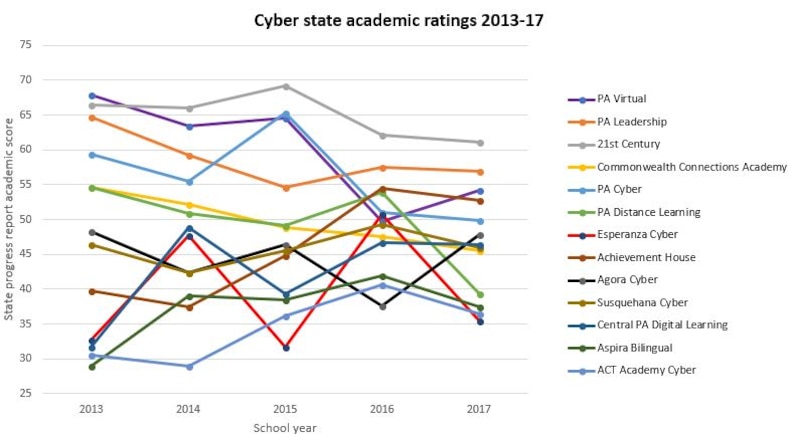

Out of the 13 full-time cyber charters in Pennsylvania, educating over 34,000 students, only four have come close to receiving a passing grade of 70. The rest have received the lowest rating on the state’s academic rubric every year.

21st Century Cyber Charter comes within a few points of passing each year, and it’s the only one that can make this claim. Pennsylvania Cyber, Pennsylvania Leadership Cyber, and Pennsylvania Virtual Cyber have all come close in recent years, but fell in the ratings by 2017.

Credit: Greg Windle. Data from Pennsylvania School Performance Profiles, compiled by the state Department of Education.

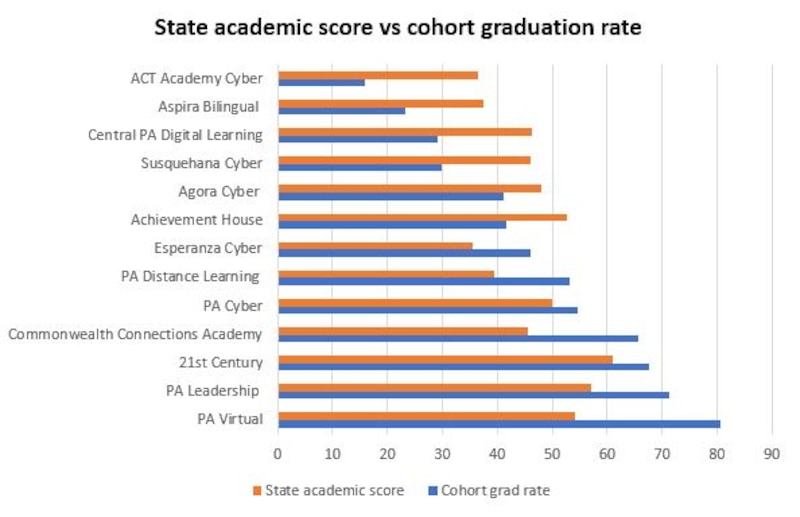

The graduation rates range from great to abysmal, and there is inconsistent correlation between the state’s academic scores for the charters, largely determined by student proficiency on tests, and schools’ graduation rates.

Esperanza Cyber, for instance, has the lowest academic rating (35), but a typical graduation rate for a Pennsylvania cyber (46 percent).

ACT Academy Cyber has a similar academic score (36), but its four-year cohort graduation rate in 2017 was just under 16 percent.

At the same time, 21st Century Cyber had the third highest graduation rate (68 percent) and the highest academic rating (61).

PA Virtual Academy had the highest graduation rate (80 percent) and the third highest academic metric (54).

Credit: Greg Windle. Data from Pennsylvania School Performance Profiles, compiled by the state Department of Education.

Although the Pennsylvania Department of Education has not cracked down on these cyber charters, there are efforts underway in the House and Senate to reform how they operate.

Senate Bill 551, now in the education committee, would allow districts to refuse per-pupil payments to cyber charter schools if they offer their own in-house cyber program – just as Philadelphia does. The only requirement is that the in-house program must be “equal in scope and content to an existing publicly chartered cyber.”

Philadelphia created its own cyber program, Philadelphia Virtual Academy, five years ago in partnership with the Chester County Intermediate Unit, which has experience running its own in-house cyber program. The program helped stem the tide of tax dollars flowing out of Philadelphia to cyber charters around the state, but the state academic scores are low for Philadelphia Virtual as well. One advantage for students is that Philadelphia Virtual Academy, unlike some cyber charters, allows students to attend classes in person whenever they choose.

Besides the package introduced by Roebuck and other Democrats, other pending legislation in the House would reform cybers.

Republican State Rep. Mike Reese’s bill, HB 97, would allow school districts to reduce per-pupil payments to cyber charters. First introduced in 2017, the bill has been moving back and forth between the education and appropriations committees for almost a year.

It has picked up some amendments during that time. Although the bill would have originally saved the state $47 million, the mechanism to reduce per-pupil payments has been weakened enough that it would now provide only $26 million in savings. Philadelphia went from potentially saving $6.7 million to $3 million in the bill’s current form.

Roebuck, chair of the House Education Committee, first put forward his bills in 2017 as a statewide charter-reform package. The most recent report on that package frames them as a response to the inadequacy of HB 97, the original charter legislation that hasn’t been significantly amended since first enacted in 1997.

Roebuck’s report found that the average statewide academic performance of charter schools was well below the average rating for traditional public schools, and cyber charters were rated even lower than brick-and-mortar charters.

But his latest package of bills does not contain provisions directly targeted at cybers.

“The core idea of our legislative package is this: charter schools and traditional public schools should be treated equally under the law,” Roebuck said in a statement. “Both receive tax dollars and both are already considered public schools under Pennsylvania law.”

Part of that legislative package is HB 1198, introduced by state House Democrat Mike Carroll, which would take significant excess fund balances at all types of charter schools and return them to the school districts that make annual per-pupil payments to the schools.

Larry Feinberg has his own frustrations with cyber charters and gw attributes them to a poorly written charter school law. Feinberg has been a school board member in Haverford Township for over 20 years, is on the board of the Pennsylvania School Board Association, and co-founded the Keystone State Education Coalition — a group that advocates for traditional public education, including stronger regulations on charters.

“Every month in school board meetings, I have to approve payments to cyber charters,” Feinberg said. “Our test scores are 30, 40, 50 points higher than theirs. We never authorized any of them. … They are all authorized by the Pennsylvania Department of Education. That allows them to reach in and take our tax dollars.

“There’s just no way it can cost as much money to educate them without a building and full-time staff. So there’s huge profits to be made.”

In Pennsylvania’s cyber charter scandal, the former CEO of Pennsylvania Cyber, Nick Trombetta, has yet to be sentenced after siphoning $8 million from the school — used to finance a lavish lifestyle. He was indicted by a grand jury on 11 counts of tax fraud and conspiracy charges in 2013, and pleaded guilty to conspiring to defraud the Internal Revenue Service. Trombetta and his accountant are scheduled for sentencing in July.

The school, still Pennsylvania’s largest cyber charter, has cut ties with Trombetta. The current enrollment exceeds 11,000 students.

Feinberg pointed out that Trombetta was ultimately convicted of tax fraud, not embezzlement, because the law is so lenient about how charter money must be spent.

“He was making so much money he couldn’t spend it all, but he didn’t even break any state law — he was just convicted on tax evasion,” Feinberg said. “As the charter law is written, it permits that $8 million he gave his organizations.”