This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

A rally at Temple University for Black Lives Matter week drew more than 150 teachers, students, parents, and activists and called for more counselors and fewer police officers in the city’s schools, anti-racist training for teachers, recruitment and retention of more black teachers, and an end to zero-tolerance discipline.

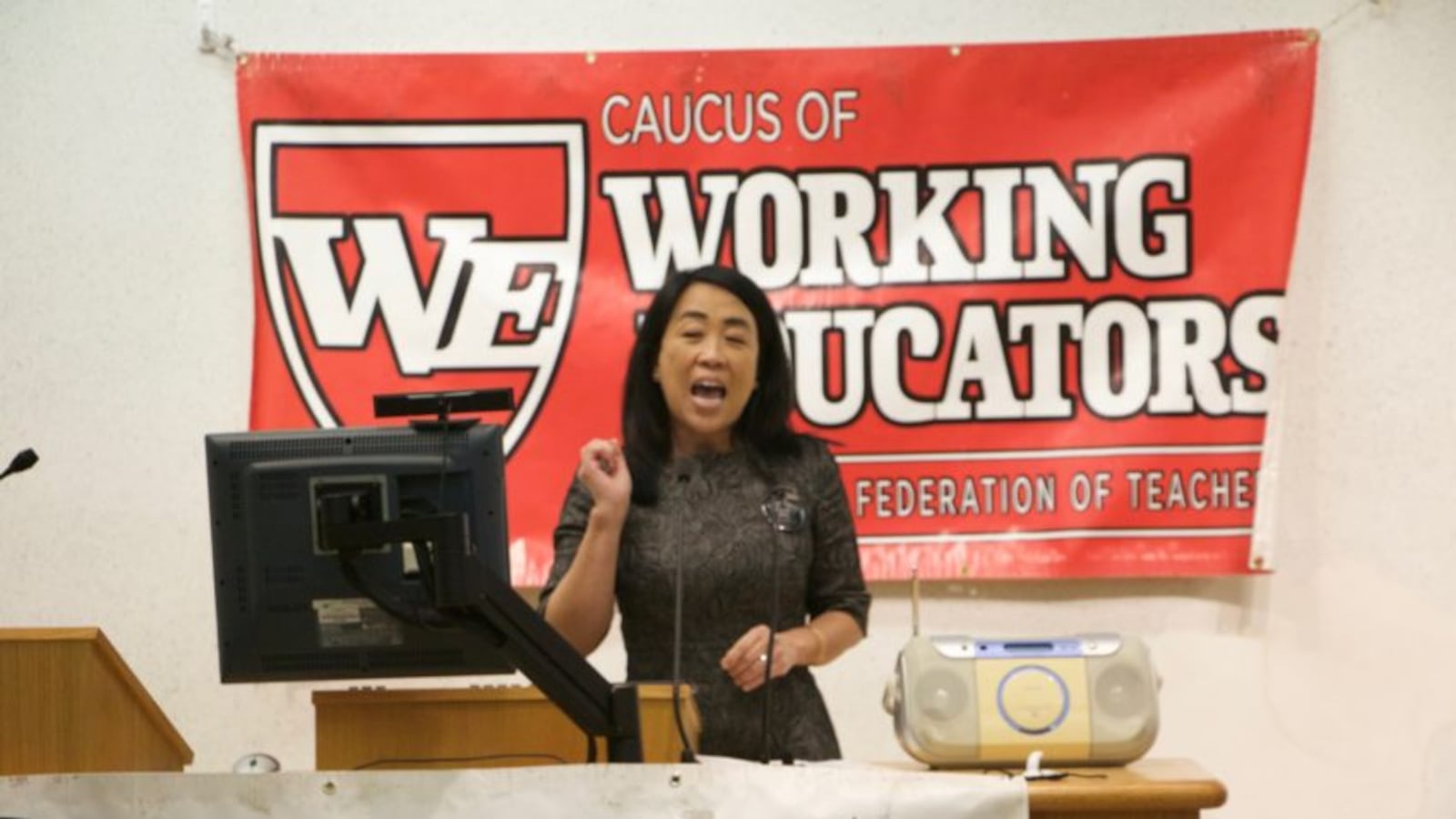

City Councilwoman Helen Gym opened the rally Wednesday by announcing that she had introduced a resolution in City Council to endorse Black Lives Matter week in schools. That resolution passed. Another of Gym’s resolutions, which is still being considered, would urge the Philadelphia School District to permanently ban suspension for students in 1st through 5th grade.

The rally brought people together from all over the city.

Fiyinfolu Akinnodi, president of the Black Students Association at Northeast High School, said their goal is “not to create another handful of successful black people and call them exemplary chosen ones, but to create an environment where every child of color can succeed because of their environment, not in spite of it.”

Jacqueline Wiggins, a committee person, said, “Black Lives Matter Week at Schools provided a forum for presenters to address the significant role of educators in ensuring that black and other children, youth, and adults do more than survive, but thrive under oppressive systems designed to stilt their positive growth.” Wiggins is also a member of Stadium Stompers, a group of activists trying to prevent Temple University from building a stadium in the middle of North Philadelphia.

Monique Perry, a member of the Caucus of Working Educators, which organized the week, and Black Lives Matter, said, “As a graduate student and educator, the rally for Black Lives Matter at School was motivational, affirming, and powerful. I feel even more committed and supported in organizing for better conditions in schools, increased safety for students, and racial justice.”

The week featured evening events that were open to the public, and it will culminate with a panel on gun violence from 4 to 6:30 p.m. Sunday at the Church of the Advocate, 1801 W. Diamond St.

One-woman show: Blak Rapp Medusa

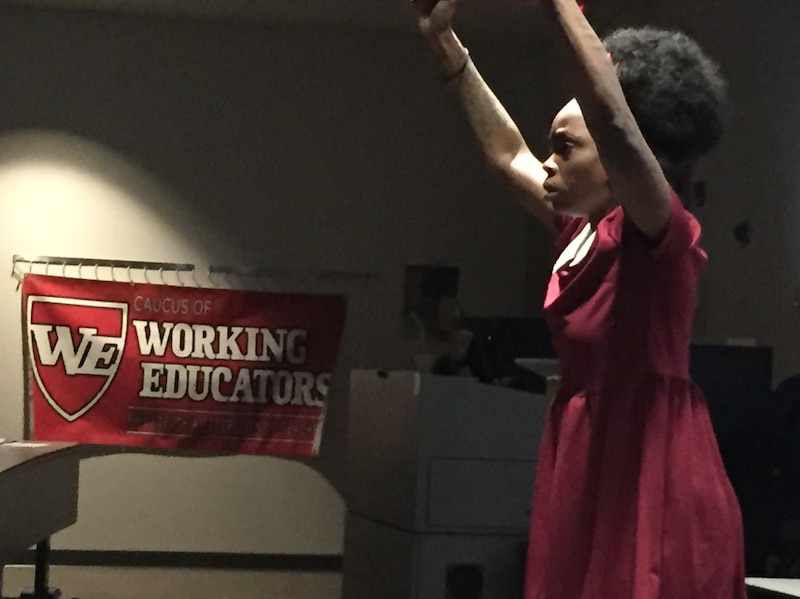

On Thursday, the Working Educators Caucus invited the public to a one-woman show and discussion. Blak Rapp Medusa, whose real name is Melania Carter, is a Pittsburgh activist whose work has centered on racial and economic justice. She performed a play she wrote about how trauma impacted her life when she was growing up and moving among foster homes and sometimes living with her biological mother, who had a history of relationships with abusive men.

Carter’s play has three acts, which take her from childhood through graduate school and solitary confinement in prison, where she was placed for advocating for female prisoners’ right to have more than six feminine hygiene products each month. At the event, she performed only the first act and discussed the rest with the audience.

During the performance, she wore a dress, and she moved and spoke as a young child would.

“I was raised by four mothers – no, five mothers,” she said to open the play. “Four black women and hip-hop.

“My birth mother, Mary, was 16 years old. Kicked out of the household like a bird leaving the nest too soon. Wanted between prostitutes, and not ready to lose. Not ready to be erased. Addicted to survival – not ready to be a mother of it.”

Melania Carter performs her one-woman play at the Community College of Philadelphia. (Photo: Kelley Collings)

Carter wound up in foster homes, where she had attentive caregivers, but she acted out, in part because of the trauma of witnessing her mother being beaten by her boyfriend.

“Sound of flesh to bone – woke from sleep. Crack!” Carter shouted. “I get up. I run to the top of the steps. Pause. Body falls. He lifts bike frame over him, then looks up at me. Pause. His eye contact froze all communication between my brain and my feet. Mister, please don’t hit my mom! He brings it down on her and looks up again. I froze in horrified fear.

“My little sister ran past me down the steps to my mother. She knew what to do. She was used to it.”

Carter went back into the foster system, periodically returning home and witnessing further abuse. She also spent time living on the street.

After the first act, Carter turned the lights on and opened herself up to an hour-long discussion of her life and work. Thanks to good tutoring from foster mothers, she said, she was academically advanced and placed in the gifted program. But she was later removed from the program due to her behavioral problems and was placed in a special education class.

“I was angry. So I became the class clown,” she said. “I was so disruptive, and I didn’t know how to control it. … No one wanted to teach me. So all they could do was send me way down to the classes where we’re playing with yarn. … It made me even worse.”

An audience member said that he grew up as a special education student in Philadelphia public schools, and he guessed that at least half his classmates at any given time were just like Carter: smart kids with behavioral problems brought on by childhood trauma.

“I started running track, and that was the thing that made me want to go to school,” Carter said.

Carter’s high school track career got her into the University of Pittsburgh, where she majored in Africana Studies.

“The healing came from my organizing,” she said. “My black-conscious education caused me to join some black liberation groups on campus and off campus.”

She went to her first protest after a Pittsburgh police officer shot and killed 17-year-old Antwon Rose. The officer, who had been sworn in just 90 minutes before, shot Rose in the back when he fled from a traffic stop. Rose was not the suspect that the officer was seeking.

Healing from trauma

Black women in the audience discussed the double standards to which they are held when trying to heal from their trauma. One young woman said her sister was shot and killed a few months ago in Germantown.

“In September, we had the service, and then everybody just disappeared,” she said. “I had people telling me: ‘You’re strong. You’ll get over it. …’ I did not realize how normal that conversation is for brown women.

“I was talking to a white woman the other day in Rittenhouse about how she just lost her dog, but she’s got this great support network and she’s going to therapy. That’s normal?

“We live in a broken world right now – culturally.”

Carter is now working as an organizer with Reclaim Philadelphia on an anti-mass-incarceration campaign. She’s gathered the support of local members of the black legislative caucus in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, including Democratic State Reps. Joanna McClinton, Morgan Cephas, and Summer Lee.

“The package of legislation will give women who are incarcerated feminine hygiene products, a couple phone calls, and free emails,” she said. “Right now, the system is charging women for every email, but it doesn’t cost them a dime to send it.”

Women released from prison would get job skills training and affordable housing, as has already become common for male prisoners.

“I’m a teaching artist as well. I go into the juvenile facilities and the group homes to teach young people to use hip-hop to talk about their lived experiences,” Carter said. “I teach them how to write a play, how to write a poem, how to draw a picture.

“If we don’t talk about it, then we won’t start to heal.”