This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

The theme of policing was ever present at Thursday night’s Board of Education meeting.

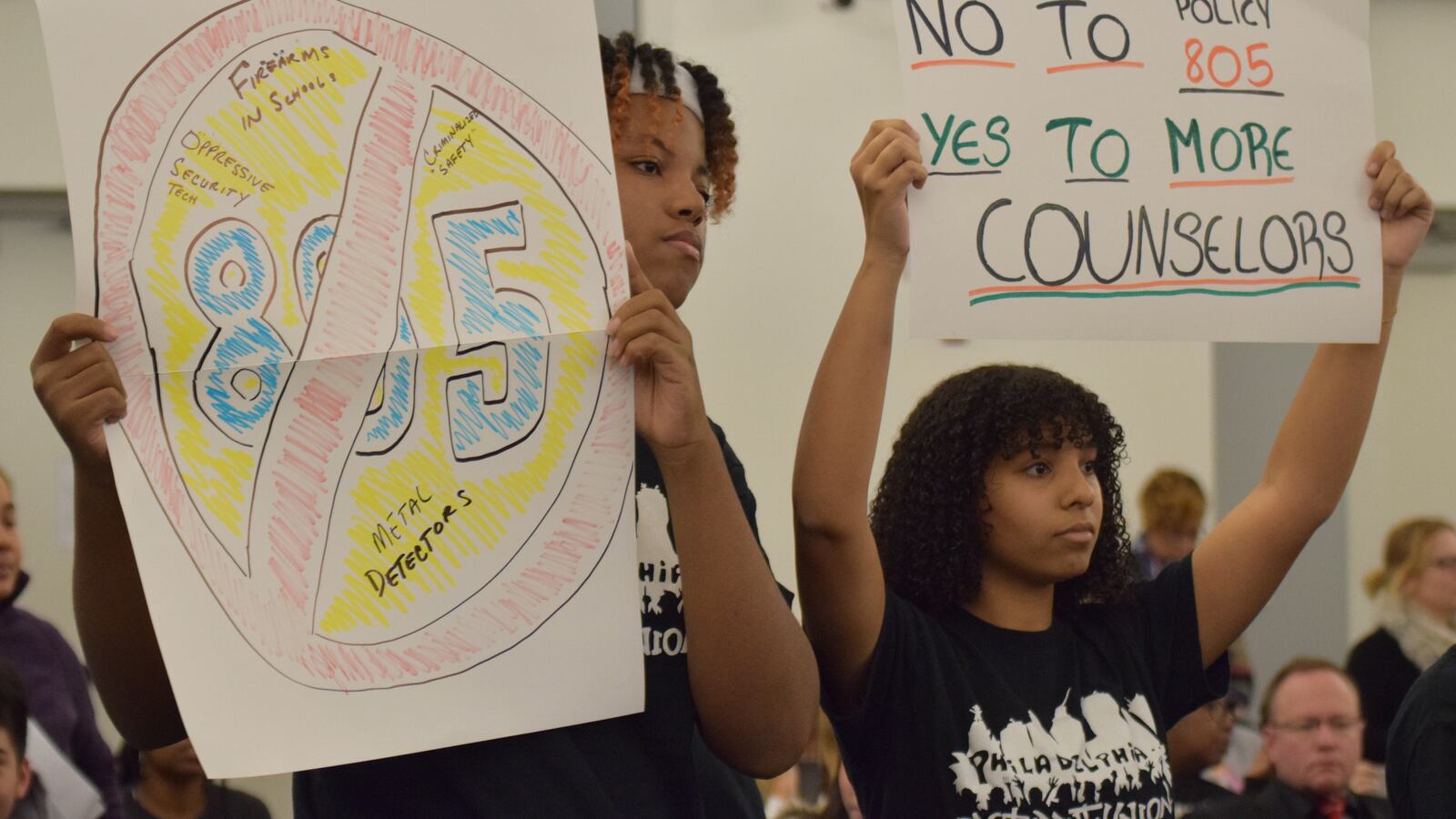

Students protested the proposal for Policy 805, which would force metal detectors into the District’s three high schools that do not have them, against the will of students and staff. In their testimony, they frequently called this policy part of a broader pattern of policing urban public schools with high minority populations that contributes to the “school-to-prison pipeline.”

At the meeting, ironically, District police argued with students who tried to enter the room after seats were full. And staff complained that another recent mandate in one cluster of schools is tantamount to policing their lesson plans, creating bureaucratic hurdles. When staff pushed back, they reported threats and intimidation from administrators in Learning Network 3.

The three high schools without metal detectors are project-based magnet schools that opened relatively recently: the Workshop School, Science Leadership Academy, and Science Leadership Academy at Beeber. Students from the Philadelphia Student Union testified against the proposed policy, and many more were unable to register to speak at a meeting where 51 members of the public had signed up.

Science Leadership Academy senior Zoey Tweh was initially stopped from entering the meeting by police, as were many other students after the seats filled up. Tweh was eventually allowed in to deliver the school’s 370 student signatures urging the school board to vote against the mandate at its next meeting in late March; the school’s total enrollment is 500.

“We believe that every school has the right to decide for themselves what safety looks like when it comes to metal detectors,” Tweh said. “We think metal detectors tend to create an environment that makes students feel more like criminals than students. We feel less safe and more as we are mistrusted.

“We are advocating for each school to be able to make their own decision and have the freedom to decide what’s best for them.”

Students testify against metal detectors

Amir Curry, a student at Science Leadership’s Beeber campus, signed up for one of the first public speaking slots in the meeting. He pointed out that his school is just a few miles from Lower Merion High School, “where police and metal detectors inside schools are non-existent.” And Lower Merion is 92 percent white, with an average household income “in the six figures.”

“The proposed [policy] is not only detrimental to students, but is being pushed with no evidence that adding metal detectors will prevent tragedies,” Curry said. “Implementing in the name of consistency without evidence is erroneous.”

“This policy is a divestment from students and an investment in the school-to-prison pipeline.”

Moly Narom, a student at the Girard Academic Music Program (GAMP), which already has metal detectors, also testified against the policy.

“At GAMP, the only students who have to go through metal detectors are the high school students,” Narom said. The school serves grades 5-12.

“It has inherently created a system of criminalizing black and brown students,” she said. “I demand that the school board members prioritize funding to provide more mental health service for students.”

She also called on City Council to end the 10-year property tax abatement on new development to provide more revenue to Philly’s schools.

Amiri Rivera, another student at SLA at Beeber, said the “intention is to prevent violence that isn’t here —it’s not in our school.

“But metal detectors tend to change communities in a way that creates distrust.”

Sam Shippen, another student at the school, saw metal detectors as a distraction from the root causes of violence in the city.

“Metal detectors are a Band-Aid on a bigger problem. If children are bringing metal weapons to school, why don’t these kids feel safe?” Shippen asked the board.

“I don’t feel that way when I go to school. I feel safe. … It doesn’t make sense for us to be policed like this,” she said. “I think that if we focus money on making our neighborhoods safer, and making kids feel safe and more support in school, then we wouldn’t need metal detectors. And we [at Beeber] do not need them.”

Julien Terrell, executive director of Philadelphia Student Union, handed the school board a thick folder of testimony from all the students who could not speak that night.

“This process has been a lot more transparent and open [than under the School Reform Commission], but I think we’re missing an important step,” Terrell told the board. “Anything that’s based on spending, there needs to be a risk assessment attached to that first before we even get to the school board.”

Superintendent William Hite said that there is such an assessment process in place for the lead paint stabilization program, and Terrell urged him to put the same process in place for the unintended consequences of all new policies.

“And that lieutenant, in the white shirt standing in the back — his treatment of students tonight was appalling,” Terrell said, referring to his “aggressive” behavior toward students who were upset that they were not allowed into the meeting.

Hite responded that they would have to discuss that further at another time.

After the meeting, Terrell explained that the students wanted to come in to hand-deliver their petition against the policy.

“The presence of police and the way they were talking to students tonight is uncalled for,” Terrell said. “If this is a place that’s supposed to be inviting, we don’t need police officers yelling at students.

“They see an authority figure with a badge getting aggressive with them and they don’t want to get in trouble. That’s not something that should happen at school board meetings.”

School board members share thoughts on metal detectors

Many of the board members expressed support for the students’ wishes, though they stopped short of vowing to vote against the policy. Member Angela McIver pointed to data from the National Center for Education Statistics that “shows the number of metal detectors used increases significantly with the black and Latino student population.”

“Our focus should be on creating a culture that puts student engagement and agency over obedience and control.”

As students requested, she said she would rather invest in mental health services like training staff about childhood trauma and hiring more school counselors.

School board member Mallory Fix Lopez agreed, saying the “bigger takeaway that we continue to hear from the public is that to get trust, you’ve got to give some of it back.”

School board member Julia Danzy, however, did not sound convinced, though she said she would “step back and study this issue.”

“In our city right now we have issues – maybe not many – with people coming into our schools, or the potential of them coming into our schools to harm our students,” Danzy said.

“Should any child be harmed, even if it was someone who spoke out against this tonight, there will be a lawsuit brought against the District,” she said.

“My feeling is, if you don’t put them in some [schools], you don’t put them in any. … So if it isn’t in some, then it will be in none.” With some dangerous schools in the city, Danzy said, “none” was not a realistic option for her.

But the school board’s student representatives pushed back. Alfredo Pratico and Julia Frank visited schools without metal detectors, including the Workshop School, where Pratico was struck by “the strong sense of community and trust.”

“We can never allow students to feel untrusted or suspect in a place where they should feel comfortable and supported,” Pratico said, reading a statement written with his fellow student representative. “We encourage fellow board members to truly evaluate the impact of these security devices and the effect they have on safety and climate in our schools. And we urge the board to vote no on this policy.”

His final words were drowned out by applause from a room filled with students and teachers.

Student representative Alfredo Pratico reads a statement that he wrote with his fellow student rep, urging the school board to vote against mandating metal detectors in all high schools. (Photo: Greg Windle)

Staff at Learning Network 3 report feeling under threat

Staff from schools in Learning Network 3 testified that a new proposed policy is being tested in their network and that teachers are under threat from administrators for pushing back against the amount of redundant paperwork. Policy 111 requires school administrators to review individual lesson plans using a rubric established by the principal.

“This year has made us feel discredited, mistrusted, disrespected and downright devalued,” said Kaitlin McCann, a teacher at McCall Elementary. “New guidelines require hours of time in order to receive a satisfactory rating on a rubric.”

McCann said that she talked to her assistant superintendent about the policy and that although she “felt heard,” the policy was still causing conflicts between teachers and administrators that were wasting everyone’s time.

“There is a clause that states lesson plans must conform to guidelines established by the principal,” McCann said. “This clause is not in our contract.”

The same policy mandates that teachers complete a new “benchmark analysis,” that involves them inputting data that is already available on SchoolNet. Teachers who fail to comply are being “retaliated” against by school administrators in the network.

“We use benchmark data, but not when the test is unreliable and invalid,” she said, tearing into the tests themselves as poorly designed and inappropriate. “A 5th-grade passage mentioned JFK being shot in the head and an 8th-grade passage mentioned rape.”

McCann said the policy feels like “policing lesson plans.”

“I feel punished and bullied. This sentiment is felt all throughout Learning Network 3.”

She was supported by testimony from other colleagues at various schools in the network, all of whom mentioned that they spoke with other teachers at their schools who wanted to testify but feared retaliation.

Jessica Way, a teacher at Franklin Learning Center, also in Network 3, delivered letters from 150 teachers throughout the network protesting the policy change, which affects all aspects of a teacher’s job “with enormous paperwork requirements” that often get denied without explanation and have to be resubmitted several times.

“We have excessive paperwork for field trips. We also have been asked by our network office to resubmit [trip] requests five times,” Way said. “Our instrumental music teacher is still owed $2,000 in extra-curricular money he has been requesting for nine months.”

“What takes so long?” Danzy asked.

“We don’t understand that ourselves,” Way said.

Board members inquire about retaliation

McIver wanted to know what the teachers meant by “retaliation.”

“There are teachers in this network who, when they pushed back against the paperwork, have received 204s,” Way explained, referring to the form used to write up teachers for breaking the rules. The process often leads to what is known as “teacher jail,” a punishment given to teachers who can’t be fired for cause. Instead, they are placed on administrative duties in the central office of the School District and no longer allowed to teach. This is the threat that teachers fear. “There are a lot of us who are afraid to speak,” Way said.

McIver said that “one of the things that’s valued as a teacher is autonomy.”

Fix Lopez echoed the complaints of those teachers, saying “this does look like policing to me.”

Superintendent Hite came back into the room after speaking about the issue with McCann, one of the teachers who spoke.

“I just spoke to Kaitlin, because I wanted to know who was asking for this type of requirement. This is not the requirement that we have as a District for our teachers,” Hite said. “In fact, the language in the policy has been rewritten to read exactly like it reads in the contract. I appreciate teachers sharing that with me this evening.

“We’re going to do something to discontinue this, because this is nothing but policing and this is not how we want our teachers treated.”