This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

For Jasmine Washington, mother of Jayden, 5, and Zoey Lee, 3, searching for a job was frustrating.

After Zoey was born, Washington was looking for work in salons, armed with a degree in cosmetology, but her primary issue was logistics. She couldn’t take just any job, even if it would be good professionally, because she always had to figure in the cost of childcare, which can be as high as $10,000 a year.

And even as she set up interviews, attended job fairs, and tried to return to the workforce, she was forced to pay the cost of childcare–before she had a job to support such an expense.

But one day, she heard something on the radio that changed everything for her. The segment was about PHLpreK, Mayor Kenney’s publicly-funded initiative to provide early education for 3- and 4-year-olds. All in the city were eligible, but the emphasis was on low-income neighborhoods and families.

Heartened, Washington got on her phone and checked it out.

One of Mayor Jim Kenney’s most central policy initiatives, PHLpreK recently turned two.

Its own formative early years have been marked by fits and starts, and controversy as the soda industry mounted a long legal challenge to the sweetened beverage tax that pays for it. But in July 2018, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court upheld the law, and now PHLpreK is ramping up its expansion, although the battle isn’t over. The beverage industry continues lobbying City Council to repeal the tax.

Whether or not PHLpreK is living up to promises made in Mayor Kenney’s 2015 campaign and during his first year in office will likely be a major issue in this year’s mayoral race.

After more than two years of implementation, the program has grown and without a doubt has changed lives like Jasmine Washington’s. But progress has been slow.

Because of the drawn-out litigation, only 250 spots opened up this academic year. The plan now is to add 1,050 spots next academic year, bringing the total number of children served by the program to 3,300, more than half of the 2023 target of 5,500.

For parents like Washington, the ability to have her children in full-day pre-K for free has not only saved her money, it has opened up job possibilities.

Before she became aware of PHLpreK, even when she found jobs, she often felt like she could not take them if they didn’t offer enough money. “I felt as though I couldn’t work just anywhere,” she said. “I had to make a certain amount so that I could be able to make the amount for daycare, and also make the amount to pay my bills, rent, utilities, the food, everything like that.”

After hearing the radio ad, she went on the website and discovered that Exceptional Learning Academy, one of the participating providers, was located close by.

“We used to walk past here all the time and I never noticed it,” she said, adding that the process of finding and applying was surprisingly simple. When she came to visit, she was drawn to the friendly nature of the staff and Director Pamela Alexander. “We didn’t feel like strangers as soon as we met, you know, it was more warm and welcoming. We liked that she gave us a whole tour around the school,” Washington said.

Pre-K boosts parents’ jobs, education

According to a parent and guardian survey conducted by the Mayor’s Office of Education this year, more than four in five–81 percent–said that PHLpreK improved their circumstances. Par-ticipating in the program allowed them to return to work (22 percent), return to school (3 percent), work longer hours (11 percent), or some combination of these (44 percent). Only 19 percent of parents or caregivers reported no change to their work or education as a result of their child’s enrollment in the program.

But even families whose personal circumstances aren’t so directly impacted see benefits.

Adam Weaver’s two youngest children have also attended Exceptional Learning Academy. His youngest daughter, who is 4 years old, is currently in pre-K at the center and his youngest son went there before starting kindergarten this year at nearby Lea Elementary. For Weaver, a stay-at-home dad, PHLpreK has allowed his family to pay their expenses without debt and do home repairs. He has also become more involved in the Home and School Association at Lea.

“I probably spend twenty hours a week working at the Home and School Association depending on the week,” Weaver said. Without free childcare, he could never be that involved. “It also benefits my older kids even though they are not in preschool anymore. So I think it has an effect that’s longer than just the year or two that the kid is in preschool.”

Primarily, however, Weaver was interested in the potential benefits for his children’s education when he visited Exceptional Learning Academy.

Pre-K kids are ready for kindergarten

Research shows that high quality pre-K significantly improves kindergarten readiness, and many studies suggest that those early gains persist well into a child’s elementary school years.

“By having more pre-K seats filled, we have seen higher levels of kindergarten readiness,” said Diane Castelbuono, the School District’s deputy chief for early learning.

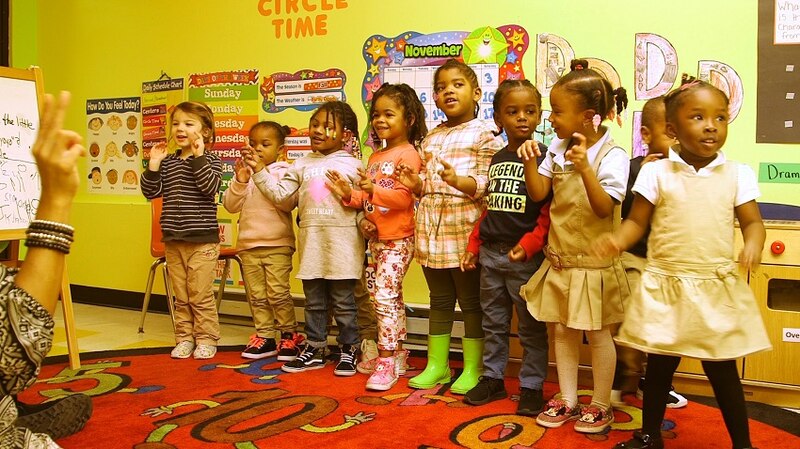

Photo by Melanie Bavaria

In Weaver’s case, the impact of pre-K on kindergarten readiness was clear. His son, now in kindergarten, “transitioned beautifully,” he said. “We don’t even have to really wait for him when we drop him off at school anymore, he just, he loves being [at school].”

Washington also says she can absolutely see the progress her children have made since being at Exceptional Learning Academy, particularly the academic gains. After school, her children often write on a chalkboard easel at home. Their handwriting has improved, a sign of increased motor skills, and they enjoy going through the colors with their grandmother.

Weaver also sees academic gains, although he regards the social and emotional learning that happens in pre-K as greatest value of early childhood education. His older son, now in the 4th grade, went to pre-K only two days a week, because at the time it was all his family could afford. The impact of full day pre-K has better prepared his younger son for the academic part of kindergarten, he said.

Without the city program, he notes, “we would not have been able to send him full time.”

Exceptional Learning Academy Director Pamela Alexander said, “The funding actually helped me to provide service for a broader range of people… It’s free and it’s funded, and it was affordable.”

“Some people cannot afford childcare,” she said. “But having the funding, they can come, and it helps them to go ahead and go to work without worrying about the high expense of childcare.”

Closing gaps in the education system

The impacts of pre-K are felt by all types of children, but research shows that the biggest gains are for low-income children or those who are English language learners, and are considered a linchpin in the perennial effort to close the racial and socioeconomic achievement gap that persists in our education system. This gap is already apparent by the time children reach kindergarten. Still, across the country where pre-K is not mandated nor adequately funded, those who need high quality pre-K the most are least likely to have access to it.

The PHLpreK program was designed to address this specifically, especially given Philadelphia’s status as the poorest big city in America.

In May 2015, on the day of the mayoral primary, 80 percent of the voters endorsed a referendum to establish the Philadelphia Commission on Universal Pre-kindergarten. Its members debated how to make sure high-risk students would be reached. Should the program have an income cap, like the statewide Pre-K Counts program or federally funded Head Start? There were (and still are) plenty of children in Philadelphia whose families make less than the income requirements for these programs. The Commission report estimated that these existing programs were reaching just under half of the 32,481 income eligible children at the time. Should a city-funded program look to fill that gap by restricting access to those families who make 300 percent or less of the federal poverty standard?

Making Pre-K universal

Philadelphia was not the first to have this debate. The same questions plagued the universal pre-K program in New York where Mayor Bill de Blasio implemented a massive expansion of publicly funded universal pre-K in the last few years, going from about 20,000 spots to almost 70,000 in just a few years. Many continue to criticize the program for not targeting low- and middle income students and concentrating the money on those who need it most.

Yet, like his counterpart in New York, the new mayor chose to make PHLpreK open to any child who meets the age requirement, regardless of family income level. The reasons were both educational and political. Studies have shown that students from all backgrounds benefit from socioeconomic diversity in the classroom, although opening up the program to all age-appropriate children hardly guarantees that outcome.

But additionally, the continued political viability of any program is much stronger if it is universal. When political tides shift or economic times get tough, means-tested social services can often be the first on the chopping block. Policies that impact the entire constituent base are far safer when making political calculations.

Still, unlike New York City or other notable examples of expanded pre-K programs like those in Oklahoma or Georgia, Philadelphia’s is far from being universal. The Commission Report estimated that of almost 43,000 3- and 4-year-olds in Philadelphia, only about 15,000 participated in quality, publicly funded pre-K. By the Commission Report’s calculation, even if PHLpreK hits its updated goal of 5,500 spots by 2023, almost 22,000 eligible children will still be unable to participate.

Yet PHLpreK has found a creative way to maximize the impact of those 5,500 spots. By design, the program remains open to any age-eligible

child in the city, but providers who serve high-poverty neighborhoods were given priority for participation in the new program. Even going into its third year, most of the pre-K providers funded by PHLpreK are in high-poverty neighborhoods, with the goal of having the greatest impact on children from low-income families, while also remaining inclusive as the system grows.

Most recent data from the Mayor’s Office of Education shows that 41 percent of participating families make 100 percent of the federal poverty level or less. Seventy-five percent of participating families make 200 percent of the federal poverty level or less. For an average family of four (the average household size for PHLpreK families is 3.9 people), that is $25,100 and $50,200 household income respectively.

For the families participating in the program, it might be small but it is mighty. The ability to send their child to pre-K has a huge impact on how they budget, advance their careers, or handle other responsibilities, all while knowing that their children are learning and will enter kindergarten a step ahead.

Washington, who is originally from Delaware County, said that access to free pre-K is one of the reasons why she has remained in Philadelphia with her children. “A lot of my friends who have kids my children’s’ ages are struggling,” she said. “I told them they should come here and try here because it’s working.”

The Notebook is one of 19 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push toward economic justice. Read more at https://brokeinphilly.org and follow us on twitter @BrokeInPhilly