This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

The number of English Learners in Philadelphia schools has grown steadily over the years as the District continues to add resources and revamp its curriculum for them. District staff explained changes to that curriculum at a Board of Education committee meeting Thursday before teachers and students spoke about continued difficulties – too few staff and a lack of pull-out classes for older students.

“We know that our students are graduating, but the goal is to make sure they have opportunities for post-secondary success,” Malika Savoy-Brooks, chief of academic support, told the board’s Student Achievement and Support Committee. She said the District is upgrading its ability to track students’ progress even after they test out of their English Learner (EL) program and is designing a high school plan to better match their needs.

The District has added new bilingual counselor assistants (BCAs) in various languages and will hire 30 more teachers of English as a Second Language (ESL) next year.

Nearly 16,000 English Learners attend Philadelphia’s public schools, up from 12,000 just seven years ago. Half were born in other countries, and many others in Puerto Rico. A large number have spent years out of school before moving to the United States.

Savoy-Brooks said the District is putting together an “advisory team” to ensure that all curriculum is “culturally inclusive.” She is also planning more professional development on “cultural competency” for teachers.

“We just do that on a surface level right now, and we acknowledge that,” she said.

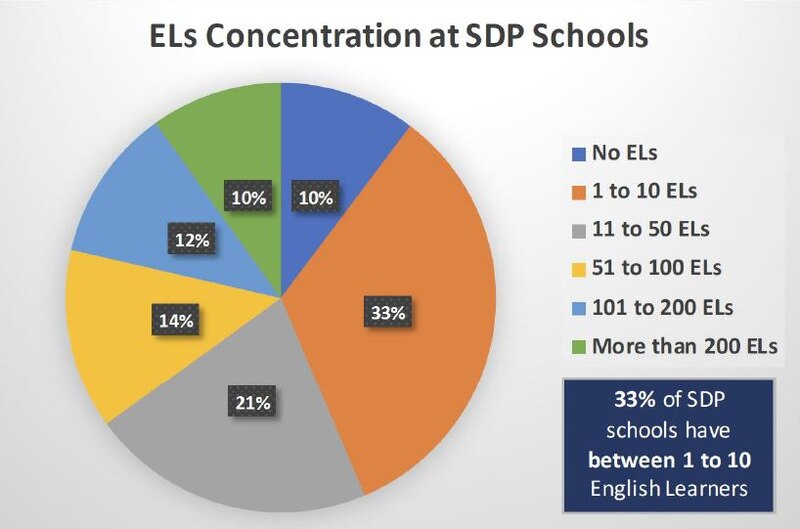

Learning Network 8 in Northeast Philly has the highest population of English Learners, with more than 4,600. And Learning Network 10 in South Philly has the largest percentage of English Learners of any District network. Although some schools in these networks have hundreds of EL students, making it easier to appropriately staff them, one-third of the District’s schools have fewer than 10 EL students.

Chart from the School District of Philadelphia.

Allison Still, deputy chief of multilingual curriculum and programs, explained that the District is “moving to models built on collaboration between the ESL teachers and the classroom, or content, teacher.”

“We’ve updated our EL curriculum, which was really driven by proficiency levels,” Still said. “Now we have a curriculum differentiated by grade-level standards with EL programming embedded in the curriculum.”

The District’s English Learners improved their growth scores this year on standardized tests, with 32 percent of students meeting or exceeding the state target on the ACCESS test, used to measure progress on learning english, compared to the state average of 36 percent. The District’s goal is to have students test out of the ESL program within six years.

The District is shifting away from “separate ESL silos,” Still said, where staff are concentrated at schools with more EL students. She outlined three “program models:” the traditional ESL model, a dual-language program now at six elementary schools, and the “newcomer program” for recent immigrant students at several high schools. But ESL teachers at the meeting said that only the program at Franklin Learning Centers offers the programming and services neccesary to qualify as a true newcomer program.

Staff and students from the newcomer program at Franklin Learning Center (FLC) packed the list of members of the public who spoke to the board. Because the District only has a limited number of high schools with any newcomer programming at all, immigrant students from other neighborhood high schools can can take the extra seats in Franklin Learning Center’s much larger program. Though the program is growing, each year there still aren’t enough seats for all the students who need it.

FLC’s program has plenty of the sought-after pull-out classes, where ESL students learn in a seperate classroom with a dedicated ESL teacher. Push-in classes are used more often when student advance to speaking higher levels of English. In push-in classes, EL students attend class with native english speakers, and an ESL teacher modifies the content for those EL students, though that ESL teacher floats between classrooms. The District now calls these increasingly common push-in classes “co-teaching,” though ESL teachers said that true co-teaching would involve a dedicated ESL co-teacher, which is rare in such an under-funded school district.

Newcomer students at FLC testified about how helpful it is to have pull-out classes with immigrant students who are also learning English, and staff urged the District to expand the program or even make it an autonomous school.

Mariam Timbo, a senior in FLC’s newcomer program who speaks French and her native language from Mali, spoke about how much the program has helped her adjust to life in a new country.

“The teachers are patient,” Timbo said. “They try to help us in all aspects of our lives, even if it’s not in the classroom.”

Timbo explained that students sit at desks in groups.

“Nobody in the group speaks the same language,” she said. “So we are forced to speak English to each other.”

Timbo said that the extracurricular activities also helped her a lot with her English.

She said she is the only English Learner on the basketball team. She also is on the yearbook committee. “And there you have to talk and explain and decide.”

Valeri Harteg, education program manager for HIAS Pennsylvania, which helps immigrants and refugees seeking asylum find support services, said she has worked with many students unable to get into newcomer programs who are struggling with low literacy levels.

“Neighborhood schools with ESL programs are generally not set up to work with these students,” Harteg said. “We have even heard concerns, in some areas of the city, that newcomer ELs who used affidavits to register for schools are not being enrolled in their neighborhood schools.”

Kristina Moon, a staff attorney with the Education Law Center of Philadelphia, presented a series of recommendations on English Learner policy to the board. She said that the District’s written policies comply with federal law, but that they are not always followed at the school level.

“Services must be based on students’ level of need, not their zip code or school assignment,” Moon said. “Students and parents complain of a lack of coordination between subject matter and ESL teachers.

“There are often waiting lists for bilingual evaluations, particularly for students who speak common languages like Spanish or Mandarin. … The District must invest in bilingual evaluators and better training.”

Kristina Moon, staff attorney with the Education Law Center of Philadelphia, speaks before the school board’s Student Achievement and Support Committee. (Photo: Greg Windle)

Moon presented the Education Law Center’s recommendations, asking that the District:

- “Ensure English Learners’ prompt enrollment in appropriate programming and reliable access to language assistance for [limited English proficiency] parents.”

- Provide “quality ESL instruction to all ELs across the District.”

- Ensure “equal access” to opportunities for all EL students, particularly regarding special admission high schools.

Cheryl Micheau, a former ESL teacher and professor who also worked in the District’s Multilingual Office, told the board that the District needed to better train principals on the needs of EL students and their teachers. Micheau also ran the District’s Newcomer Center when it first started at Benjamin Franklin High School.

“A number of teachers expressed frustration with the ways in which principals were scheduling ESL classes, with insufficient instructional time, especially for newcomers,” Micheau said. “Teachers bemoan teacher evaluations by principals, in which rubrics and guidelines designed to evaluate regular classes were being imposed on EL classes, with no apparent awareness of the special needs of ELs.

“It has been clear for many years that principals were receiving insufficient training on EL issues during their college courses. It has been well-known that training of principals on EL issues by the [District] has also been woefully inadequate, whether because the training was voluntary and few principals attended, or because the short time frame did not allow for the in-depth orientation that is so needed.”

Rebbecca Horner, an ESL teacher at Solis-Cohen Elementary School in Northeast Philly, told the board that her school has one of the highest EL populations and needs more resources.

“Although we’ve seen a rise in students in the past five years, we’ve seen a sharp decline in the supports and services they are provided, and not just at our school but district-wide,” Horner said.

She thought it was a mistake to shift — from 3rd grade on — away from push-out classes, where EL students are in a separate classroom, toward a “co-teaching model,” where EL students are in classrooms with largely native speakers.

“Instead of pulling out beginners for the entire literacy block, as we once did, we are incorporating them into reading groups, and they get an average of 20 minutes a day with an ESL teacher,” Horner said. “The new policy says that students in grades 3 through 5 should get at least one period of pull-out per day, but it was up to the principals.

“I ask you, what’s the point of having a policy if no one has to adhere to it?”

Board member Chris McGinley asked Still whether there was always an “opportunity for pull-out” for low-proficiency students.

“That’s correct, we are supporting co-teaching and [also] pull-out,” she said.

“Supporting and mandating are two different things,” McGinley responded.

Houssainatou Barry, another newcomer at Franklin Learning Center, spoke about the importance of first learning English in a classroom with others who are also learning the language. She brought an interpreter with her, just in case, but did not need him.

“In these classes, nobody will laugh at us,” Barry said. “It helps to make friends.”

She added that sometimes they’re in “different classes that force us to speak English.”

“There does need to be more mixing of American and [newcomer] students. Like in the cafeteria, people stay with others of the same background: a Spanish table, an African table, and the American tables.”

But she wants to be surrounded by other immigrants in her academic classes.

Clare Luebbert teaches ESL to newcomers at FLC. She said the program serves 180 students “and will serve more than 300 students each year as our program grows.”

“Although there are benefits to being part of FLC, in my two years working there it has become abundantly clear that in order to best serve our students, our program needs to operate as an autonomous school,” Luebbert said. She cited an “inability to provide courses tailored to students’ unique needs” and a “focus on test scores and attendance that paints our students as scapegoats and not as assets.”

“A number of school districts across the country have successful autonomous newcomer schools, and there’s no reason that our school district can’t be one of them.”

Board member Angela McIver asked which cities she was referring to.

Luebbert listed a few off the top of her head: Los Angeles, Oakland, New York City, and Atlanta.

“A lot of cities with high immigrant populations like us.”