This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

When Science Leadership Academy CEO Chris Lehmann was packing up his office in preparation for his school’s move earlier this month, one thing that he chose to keep was the sign on his office door that read: Principal 201A.

“[Thirteen] years walking into this office every day,” he wrote on Facebook. “The sign comes with me to the new space.”

The “new space” is in Benjamin Franklin High School. There, his office will likely not be in Room 201A. Still, the sign is a symbol of his open-door policy and of his intention that the culture of SLA will not change in its new location.

SLA is a 500-student special admission high school founded in 2006 by Lehmann, in partnership with the School District and the Franklin Institute. The school’s educational program is based on five principles: inquiry, research, collaboration, presentation, and reflection.

So the move – out of rented space in a former office building that cost roughly $1 million annually – was an opportunity to put these principles into action. For instance, the faculty asked the students to research office furniture to bring to the new building.

One day earlier in the spring, students seized a recently delivered chair that they had picked out for Lehmann’s new office.

The students said they wanted chairs that were breathable — less back sweat. So the wheeled chair has no solid back. It has a metal bar that wraps around most of the circular seat. A group of three students showed Lehmann each and every way he could sit in it. Facing forward. Facing backward. Sitting on the back with your feet on the seat. There were more, but at that moment they didn’t have time to explain them.

SLA’s academics place it near the top of all schools in the District, and it is highly sought-after among students of all backgrounds, all income levels, from all over the city. It is also quite integrated — 38 percent white, 37 percent black, 10 percent Hispanic and 11 percent Asian.

But the school has spent its entire existence in a high-rent converted office building at 22nd and Arch Streets with no gymnasium or cafeteria.

Benjamin Franklin, one of the city’s neighborhood schools in North Philadelphia, is a very different place. The five-story, block-long building, built in the 1960s near the corner of Broad and Spring Garden Streets, is vastly underused. Its student body is almost entirely African American, with less than 20 percent from other ethnic groups. More than a third have special needs.

Hardly any SLA students drop out, but at Ben Franklin, just 59 percent of students graduate in four years. It is the site of an evening school for students making a second try at getting a diploma.

Franklin’s new, state-of-the-art Career and Technical Education program focusing on advanced manufacturing is attracting more students from out of its immediate area. But it is underutilized.

Parents from Ben Franklin fear that SLA could expand and push out the neighborhood high school, while SLA parents fear a clash between two dramatically different school cultures. Some SLA parents, who described their school’s culture as one of mutual respect between students and staff, perceived the culture of Ben Franklin as “authoritarian.”

The cultural differences between the two schools were evident in preparing this story. A reporter was welcomed into SLA for follow-up interviews with students, but he was not able to arrange a return visit to Ben Franklin. When he tried to talk to students outside at dismissal time, the students were chased off a nearby public sidewalk by a staff member as school police watched. The staffer pushed students away from the microphone, telling them to “go home.”

SLA has won several national awards for innovation. Ben Franklin generally has made the news for incidents like one in 2016 when a school police officer was caught on tape forcibly restraining a student who wanted to use the bathroom but did not have a pass.

Even though it has fewer students than SLA, Ben Franklin has five school police officers, two of them paid for with discretionary funds that the school’s leadership could have used for another purpose — another college counselor, for instance.

SLA has one school police officer who sits by the main entrance to make sure no strangers enter.

SLA students don’t wear uniforms. Ben Franklin students do.

Ben Franklin students walk through metal detectors every morning before entering their building. SLA, for all its history, has never used a metal detector, one of three high schools in the District that made this decision.

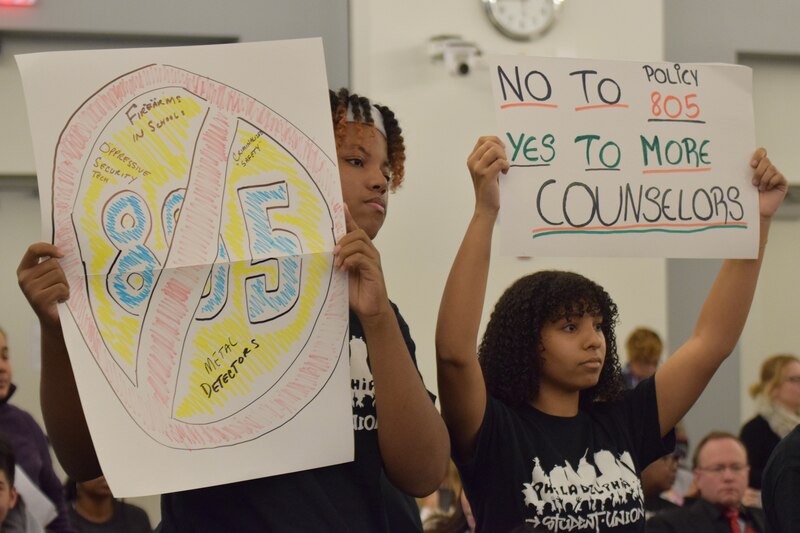

The issues raised by putting these two very different schools in the same building was brought dramatically into public view at the March meeting of the Board of Education. In the name of consistency, the board scheduled a vote that would require all schools to use a metal detector whether they wanted to or not. Members never said why they needed to do this now, although most people assumed it was in anticipation of the SLA-Ben Franklin co-location.

At the meeting, several members of the activist Philadelphia Student Union, including students from SLA, spoke passionately against this, arguing that the detectors create a prison-like atmosphere. When the board, whose members were seated last summer, passed the resolution, the vote precipitated the biggest and most raucous demonstration yet at one of its meetings. Students and their leaders shouted down the members. The board reconvened its meeting in another room, closed to the public.

Students protest Policy 805, which would mandate metal detectors in all high schools, at the March Board of Education meeting. (Photo: Greg Windle)

Opposite ends of city’s high school landscape

SLA and Ben Franklin represent the two ends of the high school spectrum in Philadelphia: selective, diverse, and high-performing schools on one end, and the neighborhood schools, obligated to take everyone, at the other. Most often, that means students who could not get into or did not apply to the citywide and special admission schools, which, to varying degrees, weed out students with poor grades, attendance, and discipline records.

Putting these two schools in the same building is cause for both trepidation and possibility.

In announcing the $39 million plan for the co-location, Superintendent William Hite touted the eventual cost savings, plus the potential opportunities for joint learning. At the same time, he emphasized that this was a co-location, not a merger, that combines practicality — taking advantage of underutilized space — with optimism that the two schools could find synergy and areas in which to cooperate and engage in joint activities.

“We fully expect that the result of this collaborative process will be an innovative high school space in the heart of the city that efficiently uses District resources and is a high-quality learning environment, featuring high-tech CTE facilities and project-based learning,” Hite said in a statement.

Committees including students and staffers from both schools were formed to help with the design process. The official goals for the renovation and updating of Ben Franklin’s building include capitalizing on the benefits of shared resources, responding to a wide range of learning styles, and “providing real-world environments for collaboration.” And there is this: “Create a safe, inviting, exciting environment for all.”

Presented with several options, the committees voted in favor of a plan in which the building will be divided by a wall down the middle, with each school occupying one half and having separate entrances. But the first and top floors will be shared spaces. On the first floor, there will be two “cafe” areas where students from each school will eat lunch, connected by a broad open lounge called the “student union.” On the top floor, SLA’s classrooms outfitted for its CTE offerings — digital media and the like — will be alongside shared learning spaces and quiet reading lounges.

SLA principal Lehmann said he is “really excited” for the student union, which was meant to feel “collegiate.” It will give students from the two schools a chance to mingle.

“When you allow people to see another group of people as ‘others,’ that’s when negative things happen,” Lehmann said. “We’re going to be sharing a building. We’ve got roommates. If you’re that guy that lives in an apartment with another roommate and the first thing you do every day is go into your room and lock the door, your roommate is going to feel a certain type of way about that.”

Students from both schools who participated in the design process, which was run by the architectural firm, described it as positive and collaborative.

“Pretty much everyone wanted the shared spaces,” said Ben Franklin 10th grader Jeramie Miller. With most decisions came trade-offs. Miller, a member of ROTC, wasn’t thrilled about that class being moved to the basement. On the other hand, his culinary program is getting new cabinets, refrigerators, and burners for the stoves.

SLA 10th grader Horace Ryans said the design meetings looked like “a lot of students spitballing ideas. It was nice to see that, even though this was a completely new group of students, we were acting like we knew each other longer than we had.”

He noted that SLA will now have classic high school features that their school has always lacked, including a gym and auditorium. No longer will gym class consist of students running through the hallways. Equity was also a concern for Ryans.

“We wanted to make sure every student had access to the same resources,” he said.

Alexis, a 10th grader at Ben Franklin who didn’t want to give her last name, initially thought the co-location was a “horrible idea,” but she is happy about the renovations.

“We really appreciate that a lot,” she said. “They’re making everything look presentable and nice — fixing things up. They’re really welcoming SLA into the school [building].”

During renovations, the Ben Franklin students have been moved around as needed; for part of the past school year, they learned in the finished classrooms. “It looks happier,” she said. “It was all dull. … It feels like a school now. Before, it was just a building we went to school in.”

Students have mixed feelings about a literal wall dividing the two schools on all but the top and bottom floors.

“Honestly, that feels really weird,” said Simone Marant, who is entering her senior year at SLA. “Being split in half makes two different worlds. Some conflict may rise from that in and of itself.”

Her classmate Arthur LaBan is less concerned about separate entrances and a divided building.

“It will allow a smooth transition,” he said. “And the shared spaces will allow us to connect with Ben Franklin students and build a community. … It’s the same people coming through the doors. So if the doors change, I don’t think that matters as much as the people.”

Students collaborate during a meeting of the design committee (Photo: School District of Philadelphia)

Culture clash

Parents are not so sanguine about the move. Simone’s mother, Leslie Marant, has sent three children to SLA. She spoke about the incident in which a Ben Franklin student was tackled by a school police officer.

“A school police officer wrestling a kid in the hallway? Over a bathroom?” Marant said. “That would never happen at SLA, and it should never happen at Ben Franklin.”

She called Ben Franklin’s culture “authoritarian” and “punitive,” in contrast to SLA. Her problem with Ben Franklin “is not the students. It’s the way people behave who are given positions of authority over those students.”

Marant said that for her, “it’s not a class issue. It’s not ‘my kid is better than these kids at Ben Franklin.’ I’m a parent born and raised in West and North Philadelphia. Absent my getting into Masterman, I am those Ben Franklin kids.”

Finding Ben Franklin parents to interview proved difficult. Sheila Armstrong, a community organizer who lives in the area, contacted several, but although many were wary about the move, none felt comfortable speaking with a reporter. She said their concerns centered on whether SLA would expand and push Ben Franklin out of its own building. School officials, including central office staff and the schools’ principals, said that would not happen. SLA was founded deliberately to be a small school with an enrollment of roughly 500 students, and it has no plans to expand.

Ben Franklin’s principal, Christine Borelli, has worked alongside Lehmann to answer the questions of parents from both schools.

“With the parents, there were a lot of concerns about the reputation of Ben Franklin — there’s so much history involved,” Borelli said, adding that many of the concerns about reputation arose from a few news articles. There was the incident when the police officer restrained the student and another about a fight on SEPTA.

“That one incident you heard about 50 times — about a fight on the subway — that’s not really representative of our school,” she said. “That was resolved pretty early.”

Yet it was clear that where trust and mutual respect mark the relationships between staff and students at SLA, Ben Franklin’s culture draws a sharp contrast.

On a spring day after dismissal, Kayla Abdur-Rahim, a Ben Franklin junior, stood a block away from the school talking to a reporter about what she said was an inconsistent discipline system and the inconveniences brought on by the construction.

“If people jump you, they don’t always get suspended,” she said. “And they never kick them out — period.

“I feel like, if they can’t even control us, how are they gonna put us together with another school?”

Her friend standing nearby cursed under her breath at the sight of the school’s culinary teacher, Keith Pretlow, approaching them with the school police looking on from the other side of the street. “I don’t care about him — we’re just talking,” Abdur-Rahim said. “He can’t stop us.”

“Oh, yes he can,” her friend shot back.

And he did. As Abdur-Rahim kept talking — “They need to get this school together” — the teacher stepped between her and the reporter, refusing to identify himself or answer questions. Instead, he palmed the side of Abdur-Rahim’s head and shoved her away, saying, “Have a good day.”

“We’re talking!” she protested. Pretlow pushed her head away again and told her to go home.

Adbur-Rahim told him to “chill,” but he kept pushing her away from the microphone. Finally, she gave up and walked away. The school police did not move to intervene.

Before Ben Franklin staff were made aware of the interviews taking place outside, sophomore Alexis said her primary concern was fighting between students. “Teenagers,” she said, shaking her head. “That’s how they do it nowadays.”

But she liked the idea of shared spaces with SLA. “I don’t want them to be completely isolated from us,” she said. “They did well on that.”

Even though, she said, “there’s a lot of stuff I don’t like” about the plan, “I am excited for SLA to come in. … It would be good at least to see them so we can get to know each other.”

Concerns about conflict

Plenty of SLA parents are wary, too. “There are still parents talking about pulling kids, which I think is disruptive to their education,” said parent Sarah Caswell. “And it’s not teaching them any life lessons.”

Caswell teaches at Lincoln High School, where her students go through metal detectors every day.

“I don’t think many parents considered the opposite end: If Ben Franklin kids have to get scanned, but SLA kids don’t,” she said. “At Lincoln, we had a shooting [nearby] last year, so I don’t care. Scan them. … To me, that’s not the hill to die on.”

Other parents have mixed feelings. Nareida Babilonia, whose son is entering 11th grade, learned about the move during his freshman year and attended the first open house for parents.

“When I got into a circle with other parents, I could tell that certain parents were a lot more worried than I was,” Babilonia said. “It was very clear there was a lot of white privilege and a lot of conversations about ‘them’ and ‘they,’ which I didn’t appreciate. Somebody even called it a social experiment, which I thought was insulting.

“The concern I was hearing from parents was about Ben Franklin having a bad reputation. And a lot of concerns like: Are we going to be separated? Is it going to be clear which kids are from SLA and which are from Ben Franklin?”

Those concerns have been addressed by splitting the school building, using separate entrances, and Ben Franklin’s uniform policy.

Babilonia said the concern about fights between students was the only one she shared, but that she was comforted by the design for use of the building and had confidence in the staff.

Her son, Jacob Prunés, said that when he first heard about the move, he was “annoyed” by the change. But he’s looking forward to the expanded facilities for his CTE engineering program. And he’s excited to have a gym next year. He’s not worried.

“A lot of [my classmates] really don’t want to move,” Prunés said. “I’ve heard some say they’re thinking about switching schools, but most of my friends are going to stay.”

SLA parent Kathleen Butts didn’t understand all the fuss, saying that parents should visit the school and neighborhood.

“The more students and parents at both schools can talk to each other in an open forum, the better it makes the partnership for everybody,” Butts said. “There are some cool things that could come out of schools sharing resources. … I’m a huge fan of service learning, and I think there’s a potential for the schools to come together to work on projects for that community.”

Ben Franklin principal Borelli said that most parents who had concerns about the school had never visited it. So she invited them. “SLA clearly has its own brand, and I would say Ben Franklin is being transformed and reinvented. … I don’t think one group of students has more than the other, but they learn in different ways.”

In fact, there was no sign that applications to SLA declined this year or that students transferred. Today, its enrollment for September stands at 509, up slightly from the year just ended.

Students collaborate during a meeting of the design committee (Photo: School District of Philadelphia)

Unity Club

A year ago, Miranda Sosa, as a freshman at SLA, had a project in her English class that required her to identify something that affects her community and figure out a way to change the impact.

She chose SLA’s pending move as her subject and formed a club for students from both schools. Throughout the last school year, they met and brainstormed ideas for shared events and activities.

“We came up with ideas for the future like a field day, where we combine the two different schools playing sports,” she said. “We’re also thinking maybe we’ll have a potluck or a dance.”

Ben Franklin sophomore and student president Maniyah Clanton said she was “nervous” when she first heard about the move, not knowing what to expect. She met Sosa and the other students through the unity club, which she organizes from the Ben Franklin side, and now says “I like change. I’m all for it.”

“The first meeting we went over to SLA during the day. They took a small group of us around their school and showed us how their day goes,” Clanton said. “I liked how they get to express themselves.”

“I also learned that SLA has their own common spaces already,” Clanton said. “And they have couches in their classrooms.”

Jeramie Miller had a great time on the tour.

“Most of the time we were just laughing and talking. There were a lot of jokes,” Miller said.

His principal cut in. “There were some parties I keep hearing about that came out of that,” Borelli said.

Miller and Clanton just smiled in response. They listed ideas that the group of students from both schools came up with for shared extracurriculars: a book club, garden club, a joint culinary class, painting club, field day, local volunteer work, art contests, a big barbecue.

Students from both schools want to share CTE courses. Borelli and Lehmann said this is a possibility for the future, but won’t happen initially. Both principals are in discussion with the District’s central office about forming some sports teams with students from both schools.

“I felt really appreciated the second time I went to SLA, because the students really listened to my ideas and we talked about everything,” Clanton said. “I stayed in touch with some people [from SLA]. … I go over there after school sometimes.”

Miller and Clanton mentioned keeping in touch with SLA junior Shyann Davis.

“I’m in constant contact with Maniyah, and we’re always talking about events we can have to bring the schools closer together,” Davis said.

A friend of Miranda Sosa, she’s taken over leadership of the SLA side of the unity committee in her free time. “We’re trying to plan an event to get the juniors together … to have a party, or get-together, with food so we can all meet.”

Ryans called the unity club a “marvelous idea.”

“We’re two families coming together in the same house,” Ryans said. “There’s going to be conflict, but it’s going to be OK.”

Ben Franklin principal Borelli put it this way:

“They’re all teenagers. They’re all high school students. They all want the same things.”