Black-run charter schools are victims of systemic bias and are recommended for closure or nonrenewal in Philadelphia at a much higher rate than other charters, a newly formed group said on Tuesday.

The African American Charter Schools Coalition held a press conference to highlight disparate outcomes in charter regulation. The group includes 21 of the 22 Black-run charters, which enroll students from 13,000 families.

By the coalition’s calculations, Black and Latino charter leaders operate 19% of the charters in the city, but account for 87% of those recommended for closure or nonrenewal over the past several years. The group also cited a study from scholars at Johns Hopkins and Tufts University showing that people of color face more hurdles in opening charter schools and keeping them operating, and they are disadvantaged more by stringent regulation.

Philadelphia has more than 80 charter schools, with a total enrollment of more than 75,000 students, or about a third of those enrolled in public schools. The school district, through its office on charter schools, is the sole authorizer.

They also sought to draw attention to the positive effects of having Black-run schools in Black communities, citing impacts that are not measured when the school district evaluates whether to keep a charter school open. They are calling their campaign “Black Schools Matter.”

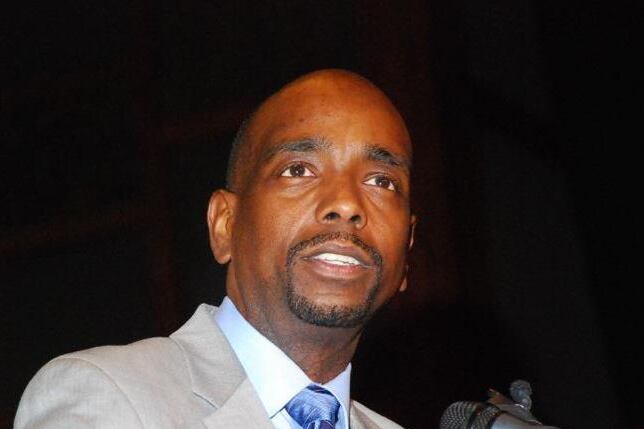

“If you look in terms of diversity and equity of staff, the Black-operated charter schools almost double the percentage of minority teachers compared to traditional charters and the school district,” said Larry Jones, the CEO of Richard Allen Preparatory Charter School in Southwest Philadelphia.

Studies have shown that having just one Black teacher between third and fifth grade significantly improves a child’s chances of graduating high school and attending college.

Those schools also are more likely to contract with minority-operated firms and vendors, Jones said. “But the real impact is the impact in having leaders and teachers and decision makers of color have on students,” he said. “If you see all of the schools operated by Blacks and educating Black students being closed, it’s a difficult situation that is hard to explain.”

Jones’ charter, opened in 2001, was recommended for non-renewal by the School Reform Commission in 2017. The Board of Education gave it a one-year extension in December, 2018 with conditions, including an agreement to meet certain academic benchmarks. Richard Allen is now in renewal status, Jones said.

The group’s statement calls for an overhaul of the district’s charter office, “so that there is fairness, transparency, and equity when it comes to evaluation, oversight and expansion. The rules shouldn’t be different for different people, or different schools based on who is or is not on our board.”

The district evaluates charter schools based on academic, operational, and financial measures. Charters recommended for closure or nonrenewal often have not met standards regarding student proficiency in reading and math, which is mostly measured by standardized test scores. For high schools, graduation rates are also considered.

The academic measures the district uses rely heavily on test scores, but also include graduation rates, disciplinary policies, and the robustness of special education and English language learner programs.

Jones said test scores should be “one measure,” rather than an “all inclusive” evaluation of a school. But he agreed that the disparity in outcomes is not a result of deliberate intent to discriminate.

“The problem is more complex than somebody said we don’t like Black schools. If that were the case, it would be easier to fix.”

Philadelphia Board of Education president Joyce Wilkerson sent a letter to the group saying she was “excited and encouraged” by the formation of the coalition and asked them for help in advocating for more funds for both district and charter schools. She also called for changes to a state charter school law that she called “outdated, ambiguous, and inequitable.”

She noted that the issues raised by the group go beyond Philadelphia and defended the district’s system of authorizing and monitoring charter schools.

“We are committed to implementing high standards. It is this commitment that motivates us to ensure that our system of authorizing charter schools is clear, unbiased, and holds all schools accountable. Through the Charter Schools Office, we believe that we have developed this system. We have a framework for monitoring and evaluating schools that focuses on student outcomes, and we apply it equitably.”