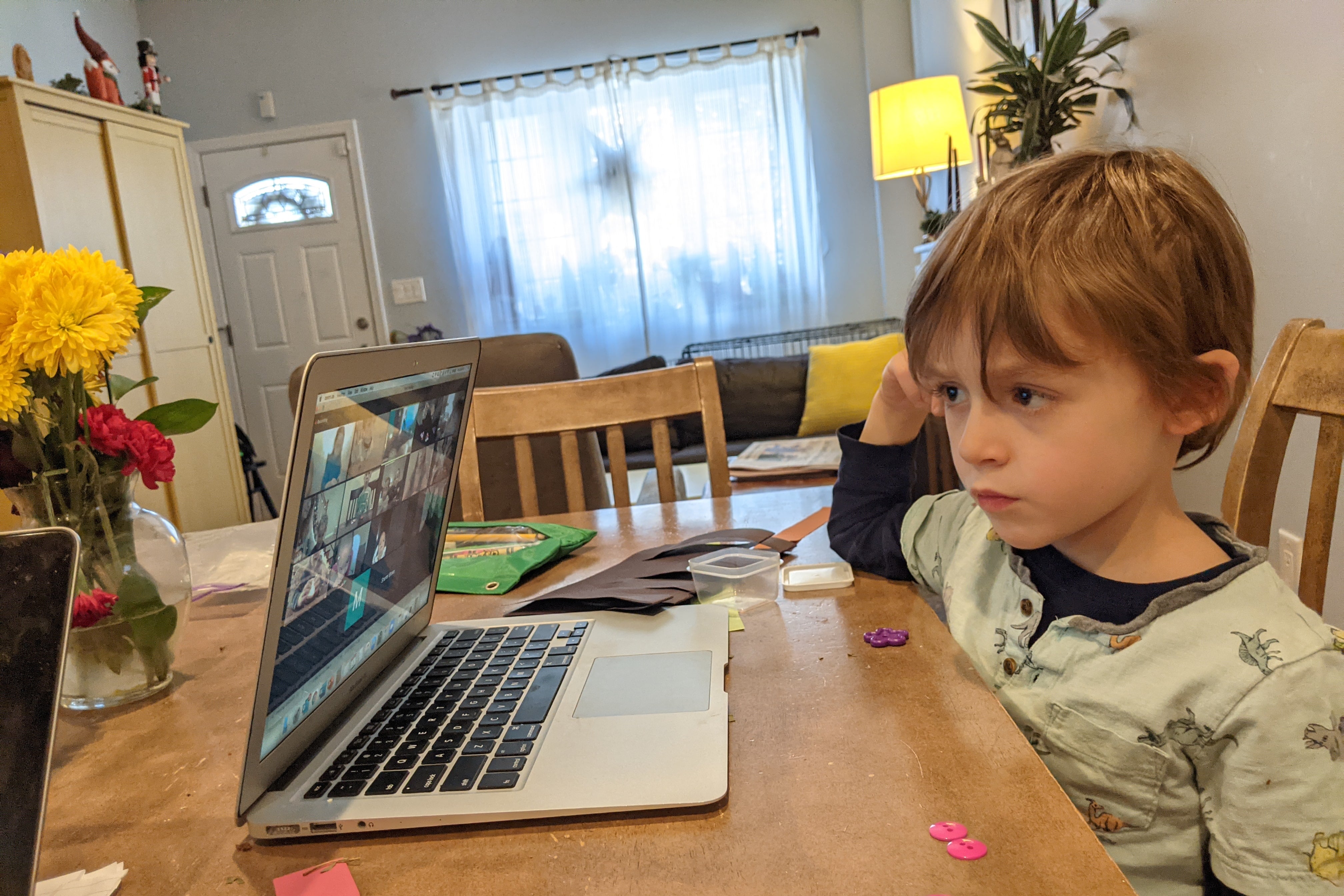

Confidently sporting a pale green dinosaur T-shirt, 4-year-old Ezra sat down at the table in his living room for “his meetings.”

Far from the boring team meetings that most adults, including his parents, have grown accustomed to in the age of COVID-19, Ezra’s “meeting” consisted of him sorting buttons by size, shape and color. Later his pre-kindergarten teacher would read a book out loud about different kids wearing clothing with various buttons, snaps and zippers.

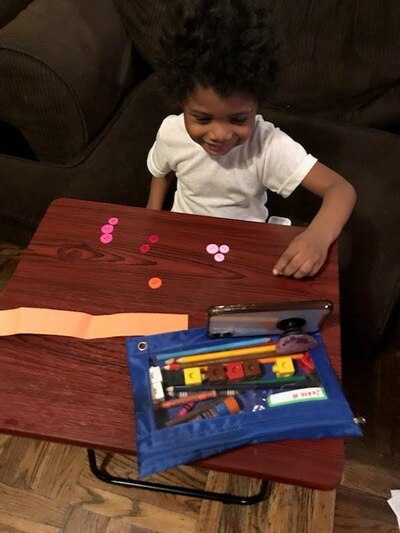

Ezra’s classmate, Jaden, 3, also enjoys being like the rest of his family. “He sees everyone doing the same thing: I am at my laptop, his mom is at her laptop, his older sister is at her laptop, so what do little kids like to do? They want to do what everyone else is doing,” said Jaden’s father, Jermaine Millhouse.

Both Jaden and Ezra attend pre-kindergarten at Kai’s Comfy Corner, one of 136 centers that are part of the PHLpreK program. Like child care providers across Philadelphia, Kai’s Comfy Corner has made adjustments to cope with the realities of the coronavirus pandemic — it’s among just 74 who are offering some remote learning.

The change has been an adjustment for families and teachers alike. Kai’s Comfy Corner enrollment dropped from about 70 students to 18, and the center adopted a hybrid model with three days in person and two days with a half hour of virtual learning. The remote days allow the teachers to deep clean the classroom and write lesson plans that integrate both in-school and at-home learning.

At the onset of the hybrid model, parents and teachers at Kai’s Comfy Corner were concerned about the impact on early childhood development and kindergarten preparedness. But several months in, some staff and parents say the center has made the best of a bad situation, with surprising results.

“From our end it is going really well, although I am sure it is much more work for [the staff]. Honestly, I have been surprised at how engaged Ezra has been in the virtual modules,” said Patrick Manning, Ezra’s father.

Millhouse said it took Jaden a few weeks to learn to sit still and pay attention during the 30-minute remote classes. By imposing a routine that mirrored the real classroom, it became easier. “We had to plan it. We had to set it up like they were in school,” he said.

Now, more than three months into the school year, the 3-year-olds and 4-year-olds interact enthusiastically with their teacher and classmates on Zoom. On one recent Thursday, Jaden jumped to answer a question about a book the teacher was reading.

“What does an author do?” the teacher asked,.

“The author writes the book,” Jaden said.

For perhaps the first time, parents are getting a glimpse into how much planning going into pre-K lessons. What may look chaotic, especially on Zoom, has its purpose.

Bryanah Tonkins, head teacher, initially tried to start with students muted, in order to mimic a classroom practice of “having your listening ears on” when another student is talking. But teachers found they missed valuable things that students said while muted.

“The environment of just letting them talk when something comes to mind is good. It helps them feel comfortable, it helps them engage with the class. One-at-a-time might work in person, but it is hard to get them to understand that only one person should talk when they are physically just there by themselves.” So instead, the audio is on for all students for the duration of the class. Sometimes children talk over each other, sometimes they get off topic, but in the end they are all learning, she said.

“It is ordered chaos,” said Tonkins, “but when you go into a classroom face-to-face and you hear that hum. You always want to hear that hum in a daycare center because it shows kids are engaged, talking, participating.”

For some families, the virtual sessions are the students’ only interaction with other children. Jillian Tropea signed up her 3-year-old daughter, Journey, for virtual classes out of concern about the health of the girl’s elderly grandmother.

“I really wanted her to go to pre-K. But with my mother-in-law, it is just not possible right now with COVID,” said Tropea. Instead, she stops by the center every Wednesday to pick up the props and instructions for the activities for the week, keeping her daughter as engaged as possible on her own and joining the Zoom classes

Thursdays and Fridays.

Tropea hopes the time, although short, makes a difference and helps to combat social isolation. She worries about the toll the lack of socialization over the last nine months has had on Journey.

Ezra’s parents too, worried about the social and emotional cost of not sending him to the in-person program. That’s why they decided to do the hybrid model. “It was a constant back and forth all summer,” he said.

During the initial shutdown last spring, they started to see the effects on Ezra and his 9 year-old brother, who is attending fourth grade virtually. With all of the talk about the pandemic and quarantine, both boys were becoming afraid of going outside and seeing other people. His parents also noticed changes in Ezra’s ability to regulate his emotions.

Now Manning said Ezra is as excited about the virtual days as the in-person ones. Even if the virtual program is only 30 minutes twice a week, the continuity of seeing familiar faces five days per week has been surprisingly significant, he said.

Early childhood educators have had to adapt too. They still have to teach the children, but they also give overwhelmed parents tools and tricks to facilitate learning at home.

“The real hard part is sitting down at the planning stage each week when we have to say ‘Ok we are reading this book and we are counting so what can we do at home, what kind of supplies do we need to give to them?’” said Tonkins.

They also need to explain to parents the lessons’ objectives, how it ties in with what is going on in the classroom, and how to extend it beyond the limited screen time the students are allowed to have with their teachers.

“It is a lesson for the families as well as the children,” said Tonkins.

Most parents aren’t trained educators, and before the pandemic, some might have viewed pre-K exclusively as child care. Many parents now are seeing what it takes to get their children ready for kindergarten, she said.

“Before parents might think, ‘Ok great, my child painted me a picture’ but they might not understand what is behind all of it,” said Tonkins.

Manning said he has learned so much from watching and observing the teachers during virtual classes. Now he finds himself talking about concepts like “structured play” and trying to bring the classroom into the home. He said he hopes some aspects of the hybrid model will continue beyond the pandemic.

“Now I am not just handing him playdough to pound it out, but we will trace an ‘A’ in it or something,” he said.

Tonkins sees more progress than ever in her students, especially notable during a pandemic in which many students and families have struggled with remote learning. She attributes that progress to the children practicing at home with their parents.

“We are kind of co-teaching almost. It is really a team effort and we have to all be on the same team as we continue his learning process at the home,” said Millhouse, Jaden’s dad.