This article was produced with support from Resolve Philly, the organization that leads Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on economic mobility.

In mid-March, some 200,000 Philadelphia students were sent home from their public schools due to the coronavirus, with hopes they would return two weeks later. That didn’t happen, and the buildings have been shuttered ever since.

From Northeast to Overbrook to Furness, students had to adapt to learning online, largely from their homes. For thousands of students from immigrant families in Philadelphia public schools, including 13% who are English Language Learners, the shutdown has posed unique challenges. There can be language barriers or confusion about the new technology. There is concern about juggling jobs with children’s course loads. There is fear about the virus, which disproportionately strikes communities of color.

But there are also victories, grace, even a touch of enlightenment. A pair of brothers cozily study on a pillow bed handmade by their mother from African fabric. Others enjoy sharing lunch as a family, eating recipes passed down by great grandparents. Many have grown closer in this isolation.

Here are the stories of three immigrant families who spoke to Chalkbeat Philadelphia about this singular time in their education experience.

It all happened so fast.

“I had stuff left in my locker. I had my personal books in my locker, my dance clothes for my dance team in my locker. I expected to be sitting [out] for a week or two and come back,” recalled Ramirrah Reid, a junior at George Washington Carver High School of Engineering and Science, of her last days attending school.

But then the principal sent out an email saying the district was shutting down. “That was my sophomore year,” Ramirrah said, “and I didn’t really get to experience it at all.”

“It all happened so fast ... I expected to be sitting [out] for a week or two and come back.” -Ramirrah Reid, George Washington Carver High School of Engineering and Science

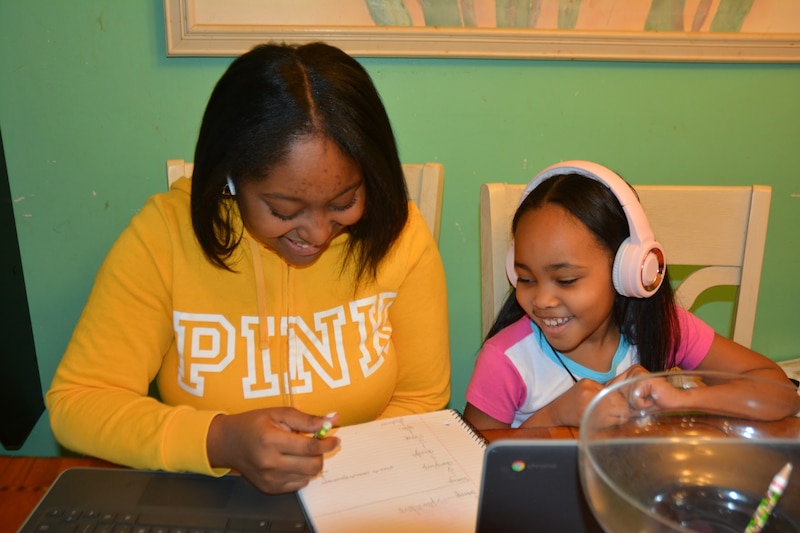

For 16-year-old Ramirrah, school is now a laptop that she uses in her home in Overbrook Park, where she lives with her siblings as well as her mother and grandmother, both of whom immigrated from Jamaica in the 1990s. As the eldest of three children, she has also taken on the role of tutor and teacher while her mother is at work as a nurse.

On a recent morning, Ramirrah watched an astronomy lesson on space missions while her sister, Samya Demercado, sat on a living room sofa in her pink and white pajamas and played a game on the cell phone. Samya had a half day and was done with school a little after 10 a.m.

“My mom, at first she was here with us, taking care of my grandmom but she just recently started going back to work so it’s just me with my siblings,” Ramirrah said. “It’s kind of a lot because I’m doing my work, then I got to make sure they’re doing their work.”

Ramirrah is juggling everything at home while still fulfilling the requirements of what she called “hardcore” classes — Honors Pre-Calculus, Honors Physics, AP U.S. History, and an English 101 dual enrollment course at the Community College of Philadelphia.

According to the African Cultural Alliance of North America (ACAN), an organization that assists African and Caribbean immigrants, virtual learning has brought on an extra burden for families. The organization provides tech training for business owners and says they are working on a grant to help families adjust to virtual learning.

“There have been a lot of issues with digital learning in the African and Caribbean community,” said ACANA CEO Voffee Jabateh. “We do get parents having difficulties...issues like trying to log onto Zoom and not having the proper internet. In some cases, parents do not have the proper tools. Some of them only know how to go online over the phone. The parents might not know how to follow up or check their work, they only take their [students’] word for it.

Reporter Samaria Bailey and immigrant students appear on The Source with Andrea Lawful Sanders - WURD Radio

Player not showing? Click here.

Ramirrah said before returning to work, her mother supervised her younger brother and sister. Now, although she has stepped into the role, she is just as, if not more, bothered by the fact that she can’t be near her close friends. While Ramirrah is not shy, she does sometimes keep to herself and felt like school “really brought me out of my shell.” She tries to stay positive, avoids thinking about the stress and keeps herself busy. But some days it’s not easy.

“I prefer to be in school - just the whole school experience – going to different classes, meeting new people, going places after school with my friends,” she said, crying. “I don’t think I’ve ever come straight home after school.”

“Going virtual,” she continued, “I’m missing out on most of my high school experience.”

Ramirrah’s sister, Samya, said she felt similarly, like remote learning has taken something from her. When she was a second grader last year at Overbrook Educational Center, she was in the annex building. This was supposed to be the year that she moved up to the big building, where she could see all the older students, including her brother, walk to lunch in the cafeteria.

“But, now I’m in my house. I’m not in the building,” she said. “I feel furious because I want to see all my friends. I can’t see any of my friends and how funny and crazy they are.”

Samya has been struck by the heavy workload she’s expected to finish every day and turns to her teacher or sister if she needs help. The computer puts a strain on her eyes, she said, so much so that sometimes she feels as though they are “burning.” Ramirrah says she also gets headaches sometimes. Their brother, on the other hand, prefers learning at home without the distraction of classmates.

But virtual learning has brought on some residuals that they enjoy. Ramirrah and Samya have come to appreciate their grandmother and mother’s food, especially recipes passed down from their great-grandmother. Before, they might have eaten the school’s breakfast and lunch or ordered takeout meals. Now, they eat more of their family’s native foods – including special Jamaican sourced frankfurters, tin mackerel with boiled dumplings, and porridge.

“Sometimes what I will do is come down and make them something to eat because I don’t want them to be sitting around the computer all day, eating chips and stuff,” said their grandmother, Marlene Johnson. “I think I feel more for the children because sometimes you can see that they are confused. [But] they do their work.”

Learning at home has been an adjustment for all of Aracely Isidoro, an immigrant from Mexico, and her four children. But the sacrifice is perhaps steepest for her oldest, Jazaret.

The 18-year-old is an advanced construction student at YouthBuild Philadelphia, an accelerated program for nontraditional students to finish high school. Learning at home means she might miss out on one of the most important pieces of her program — the hands-on training needed to eventually earn a certification in her field. Jazaret watches the local coronavirus cases rise and restrictions on in-person learning remain in place, and she feels uncertain about her future.

“It’s complicated to get your certificate without having any experience,” said Jazaret. “We are going to get our diploma [but] we might not get certified because we don’t have the required hours or the hands-on experience.”

Juntos, a community-led Latinx immigrant organization based in South Philadelphia, said such uncertainty has come to mark the experiences of countless families and called on the School District of Philadelphia to do more.

“We have seen parents weigh between taking a job or leaving their children home alone, older siblings becoming teachers for their younger siblings, all while families fight for internet access to ensure their children are able to attend classes and then resolve issues that come up with the online platforms all in a language that is not their own,” Juntos said in a statement.

Learning inside the family’s three bedroom home in South Philadelphia, Jazaret misses having a “seat partner” who she could ask questions of in class. Jazaret described her new version of class as “in my bed … just staring at the computer.”

“When [we] go to normal school, if you have a question, you ask your seat partner. Now, it’s really difficult because we don’t know each other because our cameras are off.” -Jazaret Isidoro, YouthBuild Philadelphia

“Now, it’s really difficult because we don’t know each other because our cameras are off. We don’t have that connection or communication,” she said, adding that she sees a change in her siblings, too. “Normally, [I’m] used to after school, after three, the kids come in, they are full of energy but now it’s quiet.”

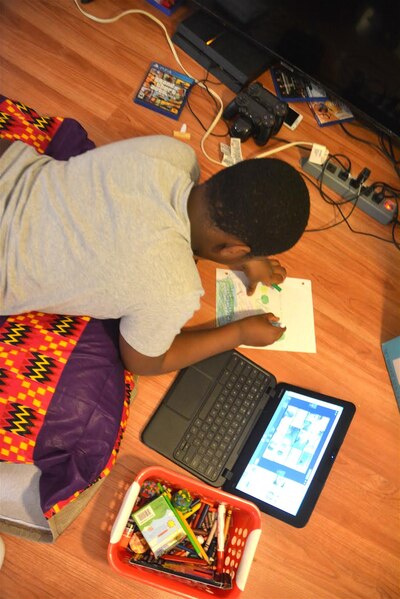

Her brother, Alan Perez, an 8th grader at Andrew Jackson School, also attends class in his bedroom. He said he initially liked the idea of virtual learning because he didn’t always enjoy learning in a school building. “I was actually pretty happy that we weren’t going back. I didn’t really like going in person. I thought it was nice to have freedom to roam around the house on breaks,” he said.

“My feelings have changed drastically.”

Alan knows that he procrastinates without someone watching him, especially when his mother is downstairs, and not able to mind him. So he admits he sometimes doesn’t pay attention in class. “It’s like, since I’m not being watched, I drift off doing my own thing…mostly playing video games,” he said. “I do feel I am learning. I still am able to turn in my assignments correctly.”

Jazaret and Alan said they also assume tutor roles for their two younger siblings, Angie, a fifth grader, and Francisco, a third grader. Their mother, who doesn’t speak English, said through a translator that their stepping in has been a huge help, as has a nearby church that offers tutoring two days a week.

“It’s very hard for me and my kids. I also didn’t study in Mexico, so the method of learning is very different and also much more advanced,” she said, noting that Jazaret and Alan’s help with the younger kids “makes it easier [but] it’s still complicated.

“In the case of my younger son - he has a hard time focusing on the task at hand. The teacher will send a message if the younger child is missing homework but there is no additional support,” she said.

One of the silver linings to having school at home for the family is the growth of their relationships. Jazaret and Alan observed that Angie and Francisco, who’ve been mostly immersed in American customs, are now more exposed to Mexican food and language.

“My younger siblings, they are speaking more of their native language, instead of English, which is good. During lunch or breakfast, we are eating more of our native food than normal school. They are eating better now. Here, we eat what we normally eat and our own fresh food, compared to the school’s processed food,” said Jazaret. “That’s one of the great things that came out of it. You have more time to connect or talk to your family than you would normally.”

When the Mohammed brothers, Aunullah and Mohammed-Muftahu, awake in the morning, the first thing they do is pray the Fajr prayer, one of the five daily Islamic prayers. They then shower, eat breakfast, and by 8:30 a.m., they are logged into their laptops for school. This is their regular routine, and according to their mother, Halimatu Mohammed, it has been slightly modified for virtual learning – as have other parts of their lives.

Mohammed, originally from Ghana, has to balance supervising her sons’ learning with her work as a visiting scientist at Northeastern University, including writing scientific papers and editing journals.

“I have to put a lot of these things on hold. Or, the majority of my work is done when they are asleep at night,” said Mohammed, who moved to the U.S. in 2000. “Whereas, I was a little bit relaxed on the sleeping time, now I have to be a lot stricter. I realized having a calendar for each child helps out a lot.”

Kou Dolo, an ACANA social media consultant, said the pandemic is a challenge for many working parents, including African and Caribbean business owners who have had to bring their children to work. She observed one instance recently while visiting a store along a majority African business corridor.

“There was a student in the store during [business] operations and people kept coming in and out and she was basically in class online and there were a lot of distractions [and] asking the teacher, ‘Can you please repeat?’” said Dolo. “I spoke to the president of the small business owners association and he talked about how they can’t leave their kids alone, they don’t have a babysitter, they have to bring their child to work with them.”

An active parent, Mohammed serves as a parent representative board member for her sons’ school, Independence Charter School - West, and regularly contacts their teachers to ensure they are on or ahead of target. At home in their Southwest Philadelphia neighborhood, such engagement translates into what the eldest, 12-year-old Aunullah, described as a mom who is stricter than the teacher.

“I can’t get as loose as I want to because in school there’s certain things that I can do, that I can’t do in here. At school, if you want to stand up, you can stand up. Here, if you stand up, you have to sit down, and you have to pay attention in class,” he said. “Mom is stricter when it comes to school. She takes it really serious.”

On a late November afternoon, while Aunullah participated in a science lesson on the four hemispheres of the Earth, a piece broke off of his headphone jack. It’s the fourth pair he’s had. Seated nearby, his 9-year-old brother, Mohammed-Muftahu, listened intently to a Spanish class while the teacher reviewed the terms for the three meals of the day.

The brothers sat at a table usually used by their mother for some of her seamstress work. Mohammed observed the boys, providing direction in her Ghanian language, Hausa, while also tending to their three-year-old sister. At one point, she urged Aunullah to put his headphones back on, to which he responded with a minor protest.

“I don’t like it,” he said. Both sons wore casual clothes, as opposed to a uniform that they would normally have worn if they were in the school building.

At other times, they attend class in their rooms, planted on a pillow bed Mohammed recently handmade using an African-printed fabric, an effort to make them feel comfortable while online.

The issues they’ve experienced are similar to those reported by other families – computer freezes, sound failures, screen fatigue, wandering minds, and some sibling discord.

“I was in the room doing my class [and] he kicked me out while I was lying down,” said Mohammed-Muftahu, pointing out one of his brother’s antics. “When I’m not looking, he will come in my class and start [throwing] his hand up. It’s annoying. Sometimes, he types all of this stuff in the chat and the teacher says stop but it’s not me.”

Aunullah admitted that he is prone to distractions and will play games while his teacher is prepping lessons or if he finishes his work early.

Ms. Mohammed said the games were initially a problem, but through a rewards system she’s created, she’s been able to rein it in. She describes the entire experience as an adjustment – from the all-day management of the kids while tending to her own business to the constant buying of headphones and having to visit the school for supplies. But on a broader plane, she describes it as a “blessing.”

Because they are home more, the children are learning more of her native language — and she’s learning different sides of their personalities.

“I deeply appreciate it now that my kids will actually…initiate the conversation in my language and now it’s like a competition for them. I really love hearing them speak it,” she said. “These times are affording that and it’s allowing me to know my children. I feel like I’m a lot closer to them.You get to learn the different personalities of the kids. So, it’s like a blessing in disguise.”