This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

The Notebook prepared this report on early childhood education in Philadelphia for our spring print edition before the full force of the COVID-19 pandemic hit. We are posting the stories from the print edition online this week along with updates from the providers and advocates we featured. We asked them to explain what they – as well as the city, state, and federal governments – are doing to keep the industry alive so that when normal business resumes, the sector will be prepared. You can read about that here.

As we have already reported, the crisis presents an existential threat to child care and early childhood education in Philadelphia and beyond. Whether for-profit or non-profit, most child care centers operate like small businesses. They rely on government subsidies for low-income users as well tuition from private-pay clients. They need both to survive. As this article explains, the sector has always operated with low margins, and even before the pandemic was facing daunting challenges arising from its fragmented public-private nature. If nothing else, the pandemic is making everyone more aware how a robust child care sector is necessary to the continuation of commerce and the functioning of society.

The Black History Month celebration is underway at Wonderspring Early Education, and Helena Walton is beaming. She doesn’t just see children getting ready for school. She sees them getting ready for life.

“For me, and a lot of other parents that are here, this is the place,” she says. “It’s like a family learning together. They’re really teaching things.”

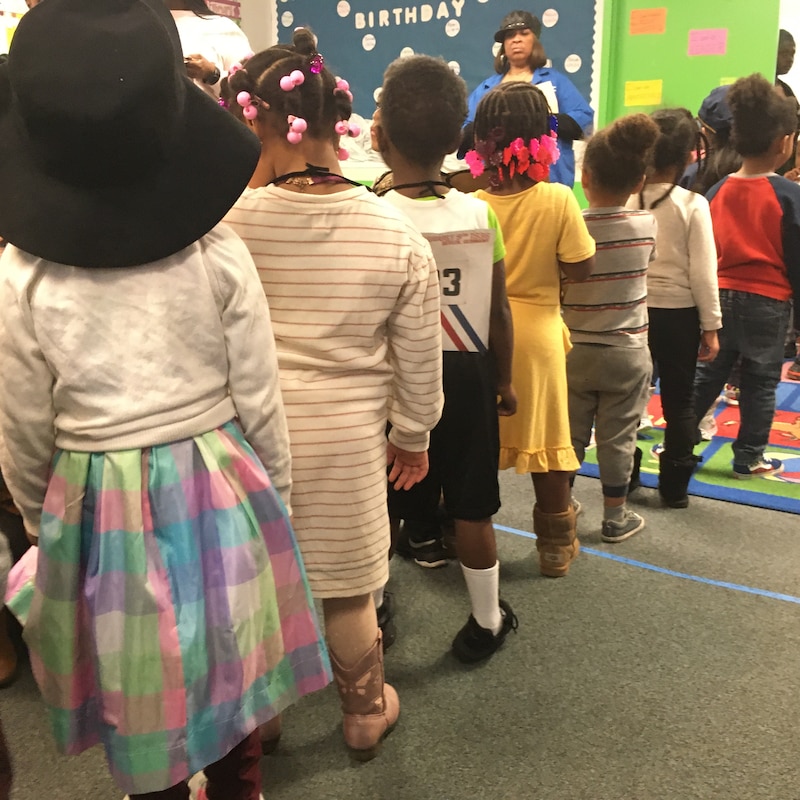

Walton is part of a packed house of parents and grandparents who have come to this child care center in Powelton Village to see their children celebrate African American achievement. Boys and girls of every color have dressed up as famous role models – Harriet Tubman, Jesse Owens, Barack and Michele Obama – to imagine themselves as doctors, artists, athletes and civic leaders. As proud families watch, the children sing, dance, giggle and applaud each other, happily acting out a future in which they star as striving heroes.

Walton glows as she watches, the timeless smile of a grown person watching children thrive. She has spent 30 years in this neighborhood, and she knows Wonderspring – until recently Montgomery Early Learning Center – well.

“It’s been a big change over the years,” Walton says when the show is over. “In the beginning you’d have children come here to just get watched over. There was not the learning experience, the social skills. Not the drive to have them do good, or be about something, or know their worth.”

As Wonderspring’s offerings have evolved, she says, the children have flourished: “Being able to speak out, being independent, being proud of what they’re becoming, being motivated.”

Quality: reading, writing, curiosity, confidence

Ask Philadelphia’s educators and public officials what distinguishes “quality” pre-K from day care, and they’ll talk about structure and rigor. Effective early education, they say, carefully and steadily builds specific learning skills. It relies on a well-planned curriculum, qualified professionals, and age-appropriate classroom settings. The “Keystone Stars” system Pennsylvania uses to rate quality measures everything from staff training and curriculum to hygiene and signage, and few would challenge the value of those metrics.

But ask parents and grandparents what makes a “quality” preschool, and talk will quickly turn from the academic to the social and emotional.

Wonderspring students at their Black History Month performance. Photo by Bill Hangley.

Lynn Dyches, another Wonderspring client, is one such grandparent. Like Walton, she was delighted by the confident and creative Black History Month performances. Her grandson and his classmates are “learning to encourage themselves,” she said, “to be wonderful people as they grow.”

That’s invaluable in a city like Philadelphia, Dyches said, where dangerous streets and overworked families can leave many young children cripplingly isolated.

“It shuts a lot of people down when they have to engage with others. And in this setting, they’re learning so early to engage,” Dyches said. “It gives them their voice. They won’t be so shy and closed in. It’ll help them deal with pressure, because they’re not so bottled up in their own heads.”

Wonderspring Director Elissha Mattheis said classroom teachers value pre-K’s social and emotional aspects as much as parents do.

“All the kindergarten teachers ask us is, ‘Can they sit in a chair? Can they regulate their emotions?’” Mattheis said. “They don’t care about the ABCs. They want that child to be able to regulate themselves, as a person.”

Educators and officials agree: the need for pre-K is most acute in Philadelphia’s lowest-income neighborhoods. But they also agree that children of every walk of life need support during the 0-6 years. High-quality preschool should be universal, they say, even if Philadelphia’s growing pre-K system still isn’t.

“There’s this concept of universal pre-K, but … we’re not really at a universal pre-K model,” said Diane Castelbuono, the Philadelphia School District’s deputy chief of early education.

In Philadelphia, pre-K services are funded and provided through a variety of state, local and federal sources, each with its own eligibility requirements and subsidies. City-funded pre-K is free for anyone. State-funded pre-K has income requirements. No single point of contact can tell parents everything that’s available. A parent walking into a place like Wonderspring might find a free slot, a low-cost slot, a full-price slot, or no slots at all.

“We have different providers, who aren’t on the same platform, who can’t share information with each other, and who are somewhat in competition with each other,” Castelbuono said.

City and District officials are working “really closely” to make it easier for families to easily access all their options, she said, but the job has just begun.

“We’re making some good headway,” Castelbuono said. “But it’s not easy to do.”

Parent needs: convenience, affordability, & reliability first

The value of pre-K is by no means universally understood. Researchers are continually discovering new facets of early development, revealing more and more about the importance of the earliest learning years.

“We’re learning so much more about the brain,” said Castelbuono. Much has been studied about what’s happening for three- and four-year-olds, she said, but “we’re learning now that 0-3 is maybe even a little more important.”

But if the science is moving fast, parents of all walks of life can still fail to understand the importance of early learning – including Castelbuono herself, who said she had to be taught not to treat pre-K like a babysitting service.

“I was always pulling my kid out of pre-K, and here I am an educator!” Castelbuono laughed. “And they were like, ‘No.’ That was really good for me.”

Pre-K providers say that parents like Castelbuono are common. Among providers’ basic challenges is to get the message across that pre-K isn’t just day care, and that parents have a responsibility to treat it like school.

“It all starts with that first phone call,” said Mattheis. “We emphasize that we need them to be involved, that you need to read to your child every day, that you need to work with your child at home … if we say that we have a concern, we need them to follow up.”

Getting parents on board with the concept can take some effort, providers say.

A basic obstacle: parents don’t always know when their child is lagging developmentally. A child that plays happily at home may act out in ways that the parent has never seen when challenged by the unfamiliar world of a pre-K classroom.

“Parents love their children more than anyone in the world, and they will overlook what we see as obvious. The famous line from a parent is, ‘He doesn’t do that at home,’” said Lisa Smith, director of the Amazing Kidz Academy in North Philadelphia. “And if the parents don’t know, they don’t know how to correct it.”

But the flip side, providers say, is that parents will quickly see the results of a quality pre-K program. After a day at Wonderspring, Walton said, her grandchildren “come home and ask questions, tell me things they learned during the day – a different culture, or some type of music, or science. They love science.”

“It’s regular schooling – it’s a school environment,” she said.

But officials know that for families, the top priority for child care is not usually its academic rigor. Whether it’s day care, pre-K, or something in between, what parents value most are safety, affordability, convenience and reliability.

Anything less is a deal breaker, officials say.

“They want quality. But they also want convenience. They need convenience,” said Castelbuono. “No one wants to be driving or riding a bus for a long time with a three year old. It’s a bigger challenge the younger the child is.”

Cynthia Figueroa, just installed as the newly-hired leader of Mayor Jim Kenney’s newly created Office of Children and Families, echoes the point.

“Unfortunately, in underserved communities, the academic offerings or the [Keystone] quality rating isn’t the first thing that ‘s being asked,” she said. “It’s, ‘Is my kid safe to walk there? When I walk in does it feel physically safe?’”

In addition, families need child care that fits their work schedules and other life demands. Figueroa spent many years running the North Philadelphia nonprofit Congreso, where she said she learned that accessible, affordable care is “critical” to family stability.

Without it, parents can stay stuck in a bad job or worse, she said. “Women couldn’t actually flee abusive relationships if they didn’t trust that there was [child care] access and stability for their kids,” Figueroa said.

So the stakes around child care are very high, she said, with accessibility, affordability and safety trumping developmental rigor. But Figueroa said that her time in North Philadelphia also showed her how badly such communities need high quality preschool. The area is full of day-care options, she said, many of them affordable and nurturing, but lacking in academic focus. That leaves too many children, particularly Spanish speakers, starting school ill-prepared.

Amazing Kidz Academy Director Lisa Smith shows signs of a quality classroom: clean floors, visible lesson plans, and welcoming, organized spaces for play and learning. Photo by Bill Hangley.

Amazing Kidz’ Lisa Smith sees those kinds of children come through her doors all the time.

“They don’t know how to line up. They don’t have patience. They don’t know how to wait their turn. They lack the social skills,” she said. “Maybe they don’t know how to write their first name or hold a pencil.”

But Smith has also seen how the pre-K curriculum helps most children close such deficits in a matter of months. In just a semester, she said, children who initially act out when frustrated can learn to work patiently on projects, play in groups, be creative or follow instructions as needed.

“They start to act like the other children – they learn,” said Smith. Out of a hundred or so children who attend Amazing Kidz in a given year, she said, only four or five have to be referred elsewhere because of behavioral problems.

The others usually thrive, she said – and families notice. Once parents see children making progress, Smith said, their expectations rise quickly. Getting parents to visit and volunteer is one of her main strategies for building demand, she said.

“When they come in and see how attentive the children are, they like that,” she said. “They get to go back to the dinner table and say, ‘at Amazing Kidz they do this and that’ … They observe everything. They talk to each other. Word of mouth is the best advertising in this community.”

City, District: expanding offerings, aligning services

To get more quality service to more young children, the challenge for City and District officials is twofold: first, to increase the availability of high-quality options, and second, to boost awareness and demand for the service.

It’s a steep task that involves aligning several major programs that operate with different funding sources, eligibility restrictions, and reporting requirements. “In government, we’re very good at confusing people sometimes,” said Figueroa. “What we’re trying to do is create some efficiency … We are at multiple tables, planning around various different [funding] streams.”

The City and District each run separate pre-K networks, and officials say that each is following separate strategies to build out their pre-K capacity.

The city’s PHLpreK program is expanding its soda tax-funded offerings. The city programs aim to serve about 3,300 children a year, currently using 138 providers. Among the Kenney administration’s pre-K priorities is to help improve low-rated centers in poor communities. Officials say they’ve helped 39 providers in “priority” communities improve from one or two Keystone Stars to the three- or four-star level.

Eligibility for the city’s programs is simple: any Philadelphia resident qualifies for free pre-K, regardless of income. A good sign for the city is that the 2019-20 cohort filled 96% of its funded slots, and served a demographically representative group: 61% African American, 12% white, 5% Asian, and 20% multi-racial or “other.”

“We feel very good about the race and ethnicity breakdown. It mirrors the census tracts,” said Figueroa.

Meanwhile, the District’s pre-K is funded by a mix of state and federal dollars, including Head Start funding. The District serves more children than the city, but has more eligibility restrictions, and less capacity to boost provider quality. About 11,000 three- and four-year-olds get served in about 160 District-run sites, said Castlebuono, and 67 of those sites are in one of the city’s 150 elementary schools. The others are in “partner sites” that include nonprofits and private providers.

In-school programs are currently staffed by District teachers, but Castelbuono said private providers could soon be working in District buildings.

“What I’m pushing for is [to] boost the number of pre-K kids in the school buildings without it actually being school operated,” she said. “You could take a provider and say, here’s your four classrooms, with your staff.”

City and District efforts are hard to coordinate, officials say, because reporting and eligibility requirements are so different. But Figueroa and Castelbuono say the two sides are working together to help “align” their efforts.

Figueroa, who was just hired this winter, said this collaboration between the city and District is just getting started. Her office will be the point of contact between the Kenney administration and Superintendent William Hite’s team, she said, and she’s begun to schedule key meetings. But city officials don’t want to ask too much too quickly, she said.

“We’re very sensitive about how best to support them, because there’s so many different moving parts for them,” Figueroa said.

One form of collaboration is already underway: the city’s health records turn out to be the best way for District officials to find children under six. For the past two years, District officials have used the city’s immunization database to send 30,000 letters annually to households with three-year-olds, informing them about pre-K and kindergarten registration.

That collaboration solved a very basic problem for the District, Castelbuono said. “We don’t know who’s out there! How would we know?” she said. “Everybody thinks it’s an easy problem to solve, but it’s not.”

And just as it’s hard for the District to know where the young children are, it’s hard for parents to find out exactly what the city and District can offer.

Currently, parents can visit the city PHLpreK website to find out what’s available for free. They can go to the District to find out what’s available with a subsidy through the state-run “PreK Counts” program. But no single place tells them everything. Castelbuono said that a priority is to develop a one-stop “portal” that connects parents to everything available, no matter who funds it.

“In this day and age we should be able to get there – we have the technology,” she said. “It’s not going to be easy, it’s not going to be quick.”

In the meantime, providers end up being the first point of contact for parents. It’s there that families often find out what’s available and how much – if anything – it will cost.

“That’s our job,” said Sheila Bonner, a supervisor at Wonderspring.

Among the challenging dynamics Bonner deals with: families on public assistance often have caseworkers or other connections that help them navigate the system. Working families who aren’t tied into public systems often have little idea of what’s available – and little time to figure it out.

“Hard-working people – they come in, and they don’t know,” said Bonner.

At Wonderspring, learning to learn

Bonner is an education veteran who has seen the change in early learning practices firsthand.

A former District employee, Bonner has spent 13 years at Wonderspring, watching the whole operation shift from a day care to pre-K mentality. It’s the right move, she said; she only wishes things moved faster.

“PhLpreK is wonderful for working parents,” said Bonner. “It’s just sad we only have 10 slots.”

The trend towards preschool goes back years, Bonner said – well before Mayor Kenney made it a priority. Interest among parents began rising as far back as the 1990s, she said, when work requirements first started kicking in for public assistance recipients. That got a lot of mothers out looking for quality child care, and started Wonderspring on its pre-K path, Bonner said.

But many parents still don’t know what real quality is, she said.

“A lot of day care has changed so much – we’re a learning center,” said Bonner. “We have to make parents know that we’re more than babysitters. We have to go to school and get degrees to do what we do. Some parents think they can just drop the children off, and they come in the next day and say, ‘She used this big word that I’ve never spoken before!’ And then they realize that we’re more than they think we are.”

Wonderspring staffer Sheila Bonner (left) with parent Rachel Hayes. Photo by Bill Hangley.

As she speaks, Bonner is sitting in the sunny office at Wonderspring, munching a muffin as the last of the Black History Month guests trickle out. With her is Rachel Hayes, a mother whose twin boys are in pre-K here.

Finding Wonderspring was a big relief, said Hayes. “Some day cares I’ve been to – pheee-ew! It wasn’t good.” The signs of low quality are easy to spot, she said: runny noses, dirty diapers, grumpy staff. “They were lazy. The quality wasn’t there,” she said.

Even costly care can be shoddy, Hayes said. “Some of these horrible day cares are still $200 a week,” she said. “And they’re licensed!”

But since she found Wonderspring, Hayes said, her boys have been thriving. They have fun at pre-K. They learn, they make friends, they come home happy. One son “used to cry all the time when we dropped him off. I came to visit him the other day, and he just ignored me and kept playing,” she said.

And slowly but surely, she said, the boys are becoming students.

“They’re counting to 20 already. All their colors, animals, basic shapes,” Hayes said proudly. “My grandmother will compare them to the little girl next door and say, ‘She doesn’t do all that!’”

The Notebook’s coverage of early childhood education is funded by the William Penn Foundation.