This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

The Notebook prepared this report on early childhood education in Philadelphia for our spring print edition before the full force of the COVID-19 pandemic hit. We are posting the stories from the print edition online this week along with updates from the providers and advocates we featured. We asked them to explain what they – as well as the city, state, and federal governments – are doing to keep the industry alive so that when normal business resumes, the sector will be prepared. You can read about that here.

Since the pandemic closed schools and most child care centers, the program Action for Early Learning has continued to work with families in its West Philadelphia neighborhood. As luck would have it, on Martin Luther King Day, AFEL volunteers assembled bags of supplies that included items that are now in short supply, including disinfectant wipes, hand sanitizer, tissues, band aids, and paper towels. They added items for children including crayons, construction paper, glue sticks and childrens’ scissors – helpful to have on hand while children are staying home. “We have been able to respond to the needs of our families during this crisis by distributing these resource bags through our civic groups within the Promise Neighborhood.” A total of 100 bags were distributed, along with donated books. Much of this was made possible through the Vanguard Foundation and PNC Bank corporate volunteers.

The program continues to share information on free meals and activities with families, and keep providers current on state and city payments. Via Zoom, it is continuing to train its Ambassadors/Navigators and helping families with online kindergarten registration and online activities.

Most of providers in the neighborhood have closed their doors, but two sites received waivers to remain open: YSI Baring House, because it is a 24-hour crisis nursery, and Xavier’s, because they have multiple parents who work in health care.

Donna Drain works full-time as a cook at Philadelphia’s Lamberton Elementary School in the city’s Overbrook section. But her part-time job is back where she lives, in West Philadelphia’s Mantua neighborhood, where she talks to parents, grandparents and other family caregivers about the importance of high-quality childcare and early childhood education.

“By the time they are three years old, 90 percent of the brain is already active,” Drain explained as she mingled one recent evening with some 150 West Philadelphia residents who filled a dining hall at Drexel University’s Dornsife Center for Neighborhood Partnerships at 35th and Spring Garden streets.

Drain, a grandmother and African American, has lived on 37th Street in Mantua for 50 years. She is one of 40 community residents who work part-time as “family ambassadors” in an innovative Drexel project that aims to ensure all children in the surrounding neighborhoods – a federal “promise zone” – are ready for kindergarten and reading at grade level by the third grade.

The ambassadors, who typically work weekends and nights, are paid $12 an hour to spread the word about just how important early education is for a child’s success in school and later life. They take community surveys, meet with family caregivers, distribute free books and even go into homes to help parents and grandparents acquire the skills they need to promote learning at an early age.

Family ambassador Donna Drain. Photo by Huntly Collins.

The idea is that trained parents and grandparents, reaching out to other family caregivers who live in the same neighborhood, will be more effective advocates for early childhood education than professionals from outside the community.

“I show the parents how they might interact with their children,” Drain explained. “If they are making spaghetti, for instance, they might say to the child, ‘I can’t find the spaghetti. Can you help me find the spaghetti?”

Even that kind of basic association between a word and the object it represents helps put very young children on the path to reading, she said.

Called Action for Early Learning (AFEL), the Drexel project, which is supported by federal and foundation funding, has drawn the attention of both national and local child welfare advocates. The program is part of the city’s Read by 4th initiative.

“AFEL has demonstrated that parents and early childhood staff have a thirst for learning how to best support the healthy development of their children,” said Donna Cooper, executive director of Public Citizens for Children and Youth, a Philadelphia-based advocacy organization. “What’s especially inspiring is that they’ve taken the time to train parents to learn the theory of healthy child development so they can help others in their neighborhood learn from trusted messengers.”

Cooper said the benefits will likely “last a lifetime” because knowledge about how to get young children ready for success in school will be passed on from one generation to the next.

Action for Early Learning is just one part of a broader Drexel initiative aimed at alleviating poverty in the neighborhoods around the university. The early learning project has two main components – an alliance of 26 childcare providers in West Philadelphia whose workers receive training and other assistance to boost the quality of the programs, and the cadre of family ambassadors who are trained to advocate for early childhood education among neighborhood residents.

“If we improve the quality of childcare programs and nobody comes, it’s not going to benefit the children,” said Maria Walker, AFEL’s director.

Tiffany Cleveland, a single mother of four children, has served as a family ambassador for more than two years. She said the training in early child development provided to AFEL ambassadors has not only helped her become a strong advocate for early learning but also improved her ability to parent her own children. At last month’s dinner, she cradled her month-old daughter while keeping her eye out for new families in the dining hall who might need to know about quality childcare. “Most of the families really appreciate the information,” Cleveland said.

Like a number of other ambassadors, Cleveland has parlayed her ambassador training into a full-time job in the child-care field.

Reaching for the STARS

About 1,100 children, almost all of them from low-income African American families, are enrolled at the 26 childcare sites. Some providers are home-based, others operate out of centers. A majority benefit from government subsidies for free or reduced-cost care provided by federal, state and local dollars, including the revenue raised by Philadelphia’s soda tax for PHLpreK.

More than half of the 26 providers are considered “high quality” under the Keystone STAR rating system used by the Pennsylvania Department of Education to evaluate childcare programs. AFEL regards the others as “rising STARS” and works intensely with them to boost their ratings.

The ratings, which take into account such factors as the ratio of teachers to children, range from 1, the lowest rating, to 4, the highest.

The family ambassador component of Drexel’s approach to early learning isn’t the only thing that distinguishes it from other programs in Philadelphia. Unlike most other early learning initiatives, AFEL is university-based, making use of Drexel’s enormous educational resources including its schools of education, law and medicine. Another difference is that AFEL focuses on the education of children from birth to age eight; by contrast, other programs tend to focus on only one age cohort – infants, toddlers, or pre-kindergarten children. And, unlike traditional programs, AFEL aims to reach children in a specific geographic area.

The target area, designated by the federal government, is bounded by the Schuylkill River, 38th Street, Girard Avenue and Sansom Street. It includes all or portions of eight neighborhoods – Mantua, Powelton Village, West Powelton, Belmont/West Belmont, Mill Creek, Saunders Park and East Parkside. These neighborhoods have some of the city’s highest poverty rates and some of the lowest literacy rates. In Mantua, the poorest of the neighborhoods, about half the residents live below the poverty line, almost twice the rate for the city as a whole.

Under the leadership of John Fry, named Drexel’s president in 2010, the university set out to forge public-private partnerships that would stimulate both economic development and poverty reduction in the immediate neighborhoods around the university while also pushing back against gentrification that would drive out low-income residents, some of whom have called West Philadelphia home for half a century or more.

In 2014, President Barack Obama named the neighborhoods adjacent to Drexel as one of 22 national “promise zones.” While the designation didn’t bring with it any federal funds, it gave “preference points” to public-private partners within the zone when they applied for federal grants to alleviate poverty.

By then, Drexel was already working with Morton McMichael Elementary School in Mantua to save it from threatened closure due to low enrollment and generally poor performance on state tests. With Drexel’s help, the test scores improved and the school, a fixture at the corner of 35th Street and Fairmont Avenue since 1892, was saved.

“The school then came back to us and said, ‘Our children are not starting school kindergarten- ready. What can you do to help us?’” recalled Walker.

The William Penn Foundation, along with the Lenfest Foundation, stepped forward with a planning grant to help launch Action for Early Learning. The vision was to mobilize existing resources in the neighborhood, including grassroots groups, to improve early childhood education in the catchments for McMichael and five other public schools in the area.

In 2016, the effort paid off: the U.S. Department of Education awarded a $30 million grant over five years to Drexel, the lead partner in a community revitalization effort. The funding, made possible by its “promise zone” status, was not just to go toward education, but also housing, legal assistance, medical care and other needs.

The model, based on New York City’s Harlem Children’s Zone, was audacious. What could a university best known for its engineering and technology programs do to improve the education of the youngest children in a predominantly African-American area where 65% of some 40 childcare centers were ranked as low quality under the Keystone STAR system?

A lot, it turns out.

In 2014, when AFEL began its efforts, fewer than 50% of the area’s 2,000 children under the age of five were in high-quality childcare, as measured by the Keystone STARS system. Today, the figure is 77 percent. Over the past six years, AFEL’s family ambassador program has organized a book-drop up and down Lancaster Avenue that has recycled more than 25,000 children’s books to give to area residents. Across 10 AFEL-affiliated childcare programs, average pre-literacy levels rose from the 31st percentile in 2014 to the 44th percentile in 2017.

Pre-literacy is measured by a standardized test in which children are asked to associate words with the appropriate picture.

Although AFEL started with an emphasis on literacy, it has now expanded to include the social and emotional development of the child. AFEL also has become a driver of jobs, job training and black entrepreneurship in West Philadelphia.

Twenty-three of the family ambassadors have gone on to full-time employment in the childcare field, and many of the childcare providers in the alliance have increased their STAR rating, becoming successful small-business owners.

A high-achieving home-based program

Xavier’s Family Childcare occupies the first floor of a three-story, red-brick row home in Mantua. It opens at 6 a.m. and closes at 6 p.m. five days a week. At 9:30 one morning in early February, nine children between the ages of 1 ½ and 5 had already had their breakfast and were engaged in an activity to promote social and emotional development.

They sat in a circle on the carpeted floor in a dining room repurposed as a classroom. Children’s books, alphabet posters and other educational materials filled every corner. One by one, the children stood and made their way around the circle, each introducing themselves by name to each of the others and asking how they wanted to be greeted. “Good morning, my name is Naleyah, would you like a handshake or a pat on the back?” After Naleyah, who is four years old, the others took a turn: Sarah, 5; Kamari, 3; Aava, 4; Nadir, 4; Kennedy, 4, and several others.

Two workers – Miss Terrie, who tends to the infants, and Miss Monica, who works with the older children – kept close watch. Through AFEL, these and other workers, most of whom live in the neighborhood, get help in earning accreditation as child development associates. Miss Terrie already has her accreditation, and Miss Monica is working on hers. The accreditation, offered through a course at Drexel’s Dornsife Center, gives childcare workers a national stamp of approval that they are qualified to work with young children in daycare and early childhood centers.

Dancing at Xavier’s Family Childcare. Photo by Huntly Collins.

When the Xavier’s children completed their round of introductions, Janelle Golden, who owns and directs the home-based program, turned to her Google Home Box. “Hey, Google, music, please!” Soon, the children were up on their feet and happily bobbing around the room as they danced to the Hokey Pokey and other songs. After that, it was time to settle down and read.

Golden, who is a youthful looking 50 years old, is the fifth generation of her family to live at 436 North Prescott, a quiet street with row homes on both sides. A graduate of West Chester University where she majored in elementary education, Golden said she had always been interested in the education of young children. In 2006, she converted the downstairs of the family home into a childcare facility. “I just keep giving the children what I can,” she said.

Through the Drexel partnership, Golden is able to give her students much more than the typical home-based program can provide. The children learn Spanish, not just English. They dance at the nearby Phil-A-Danco studio. On weekends, the children and their families get to attend educational programs at the Academy of Natural Sciences, which is affiliated with Drexel.

Not surprisingly, Xavier’s has a Keystone STAR rating of 4, the highest possible.

Officials who monitor Philadelphia’s new soda-tax-funded PHLpreK program have taken note of what’s happening at Xavier’s. “It’s fantastic what they are doing here,” said Lisette Rivera, a PHLpreK coach, who visited Xavier’s on the morning I observed.

As part of her job with the city, Rivera monitors 12 early childhood education sites, visiting each two times a month to make sure they are meeting quality standards. In order to get city funding, PHLpreK providers must have a Keystone STAR rating of 3 or 4. Rivera noted the many puzzles and LEGOs available for children at Xavier’s. “We’re going to have a lot of engineers!” she commented.

A few blocks from Xavier’s, Taylor’s Learning Academy, another AFEL-affiliated early childhood education program, enrolls 65 children from three months to 12 years old. It’s located in a modern, low-slung building at 631 Holly Mall, right next door to a Philadelphia Housing Authority complex, Mt. Olivet, that provides subsidized housing for low-income people aged 55 and older. Some of the residents of the complex have grandchildren who are enrolled at Taylor’s.

Taylor’s has a Keystone STAR rating of 3 and hopes to move to 4 through ongoing training of some 11 staff members and stepped-up parent engagement. During a recent visit, the pre-kindergarten students, all wearing dark- and light-blue school uniforms, read in small groups, with a teacher and an aide, while babies received one-on-one attention in the infant room.

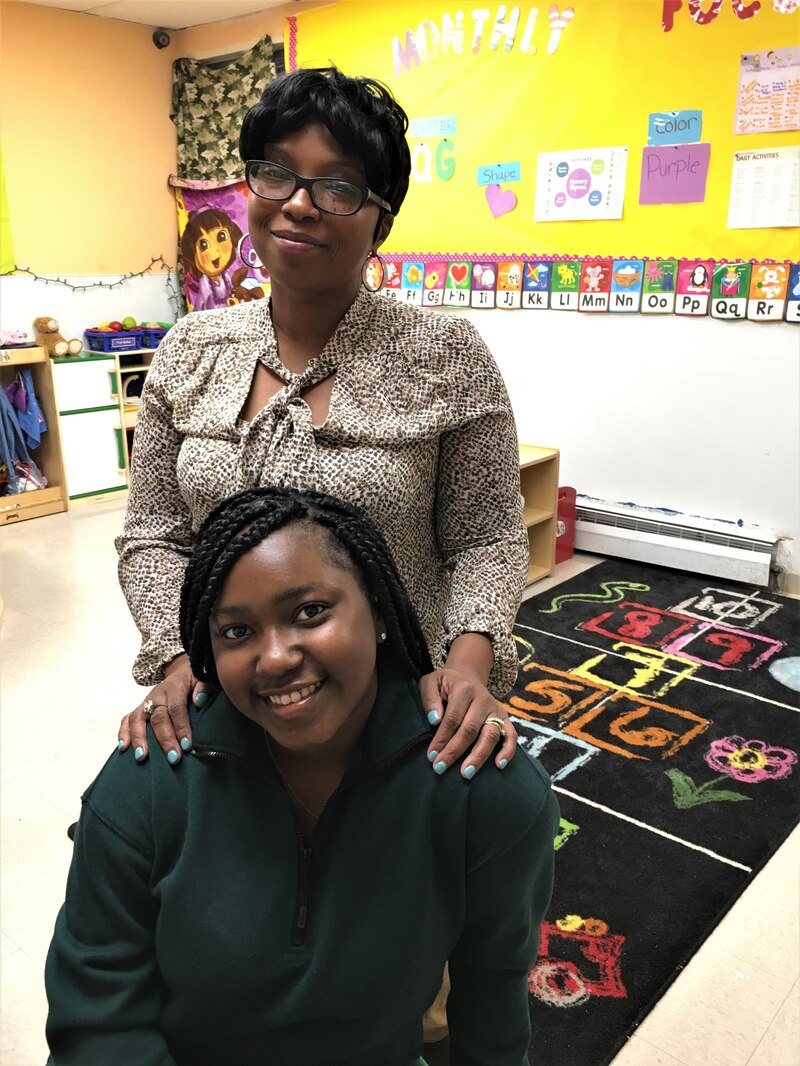

Felicia Taylor, 50, and her daughter Felicity, 16 at Taylor’s Learning Academy, which is family owned. Photo by Huntly Collins.

Felicia Taylor, whose family has owned and operated Taylor’s Learning Academy for more than 15 years, is the director.A number of years ago, she wanted nothing to do with the state’s Keystone STAR rating system. She thought it involved too much paperwork and provided too little support. But AFEL convinced her to participate.

“At first I wasn’t going to join,” she said. “But once I started going to meetings, I saw how it would benefit the children.”

At 50, Taylor is now handing off day-to-day operations at the academy to her daughter, Mariah, who is 25 years old. And ready to step up when it’s time is Taylor’s 16-year-old daughter, Felicity, who is completing a high school program that will give her a certificate in early childhood development by the time she graduates. In the program, she earns high school credit by working 10 hours a week as a volunteer at her mother’s academy.

A community of partners

A team of five people, headed by Walker, administer AFEL. The project partners with other organizations that manage different elements of the program. The 26 childcare sites, for instance, are managed by First Up, formerly known as the Delaware Valley Association for the Education of Young Children. The ambassadors program is managed by the People’s Emergency Center, a West Philadelphia organization that knows the neighborhoods well because of its longtime work on homelessness and housing. The list of other partners is long.

Walker characterized the collaboration as a “systems approach” that is sustainable because it draws on resources already in place in the community. “Our vision is that everyone has something to bring to the table,” she said. “The community has something to offer. We are not just bringing something to the community.”

As it moves forward, AFEL faces some significant challenges. One is how to retain teachers. Like the best childcare programs across the city, AFEL works hard to train teachers at its 26 sites only to see them hired away after they are trained because public schools and other employers can pay them more. To address that issue, experts agree that annual salaries for childcare workers – which typically range from $16,000 for a teacher aide to $27,000 for a lead teacher – need to be dramatically increased. The only way that can happen is if federal and state governments step up with increased public funding.

As it expands its reach to kindergarten students, AFEL must also navigate a complex web of kindergarten feeder patterns. Every year, some 350 children from the West Philadelphia area enter kindergarten at about 40 different elementary schools, some of them far outside the promise zone. “That’s a challenge to make a connection,” said Jordan Wilson, AFEL’s data manager, as he displayed a map that had red lines running in every direction to show all the different elementary schools that area children attend.

Another major challenge is how to keep AFEL’s low-income families from being driven out of the neighborhood by gentrification. As part of the 2017 tax-reform legislation, Congress created “opportunity zones” in poor areas, including West Philadelphia. If real estate developers invest in these zones, they can delay capital gains taxes and avoid federal taxes altogether on the profits they earn from their new development.

Drexel officials say they are not seeking any opportunity-zone funds for development around the campus, a decision that pleases neighborhood activists who have been fighting gentrification.

For many years, Drexel has advocated for “equitable development” – development that provides new jobs for neighborhood residents while also offering support for longtime homeowners and renters.

Among other collaborative initiatives, Drexel helps local residents stay in their homes by providing assistance with critical repairs and by helping owners untangle difficult title and foreclosure issues. It also assists those who are displaced with finding affordable rental housing in the area. On the job front, the university is part of an initiative that prepares workers for the many new jobs emerging in University City. And at its Dornsife Center, the university offers adult education, high-school completion courses, career counseling, job fairs and job training to members of the community.

AFEL ambassadors like Drain, who has worked in the program for four years, are well aware of the role that early education plays in equipping West Philadelphia youth for success in school so they will qualify for the 21st century jobs emerging around the Drexel campus and elsewhere in Philadelphia. Children who don’t get an early start often fall behind in school and never catch up, Drain said.

She recalled the story of Rakeem, a third-grader who was too ashamed to admit he couldn’t read. “I just set him down and told him, ‘Don’t you be embarrassed. If you don’t tell nobody you can’t read, you won’t get no help.’” Slowly, Drain got Rakeem to open up to her. She began showing him words she had written on notecards. First two-letter words, then three-letter words.

Soon, Rakeem was on his way, a little late, but taking his first steps toward reading.

The Notebook’s coverage of early childhood education is funded by the William Penn Foundation.