This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

UPDATED with a statement from Universal Companies on the recommendations not to renew two of their charters

The unprecedented coronavirus crisis could soon put Philadelphia school officials in a familiar position: begging Harrisburg legislators for money.

But District officials say they don’t want that to happen, even as the prospect of a billion-dollar deficit has demolished what had been a balanced budget. On Thursday, the Board of Education used its first budget hearing since the arrival of the global pandemic to urge Pennsylvania officials to keep state education spending robust even as revenues fall and to keep federal stimulus dollars flowing to local school districts.

The pandemic’s hit to the state education budget “has the potential to erase all of the progress we have made over the last eight years,” said Superintendent William Hite.

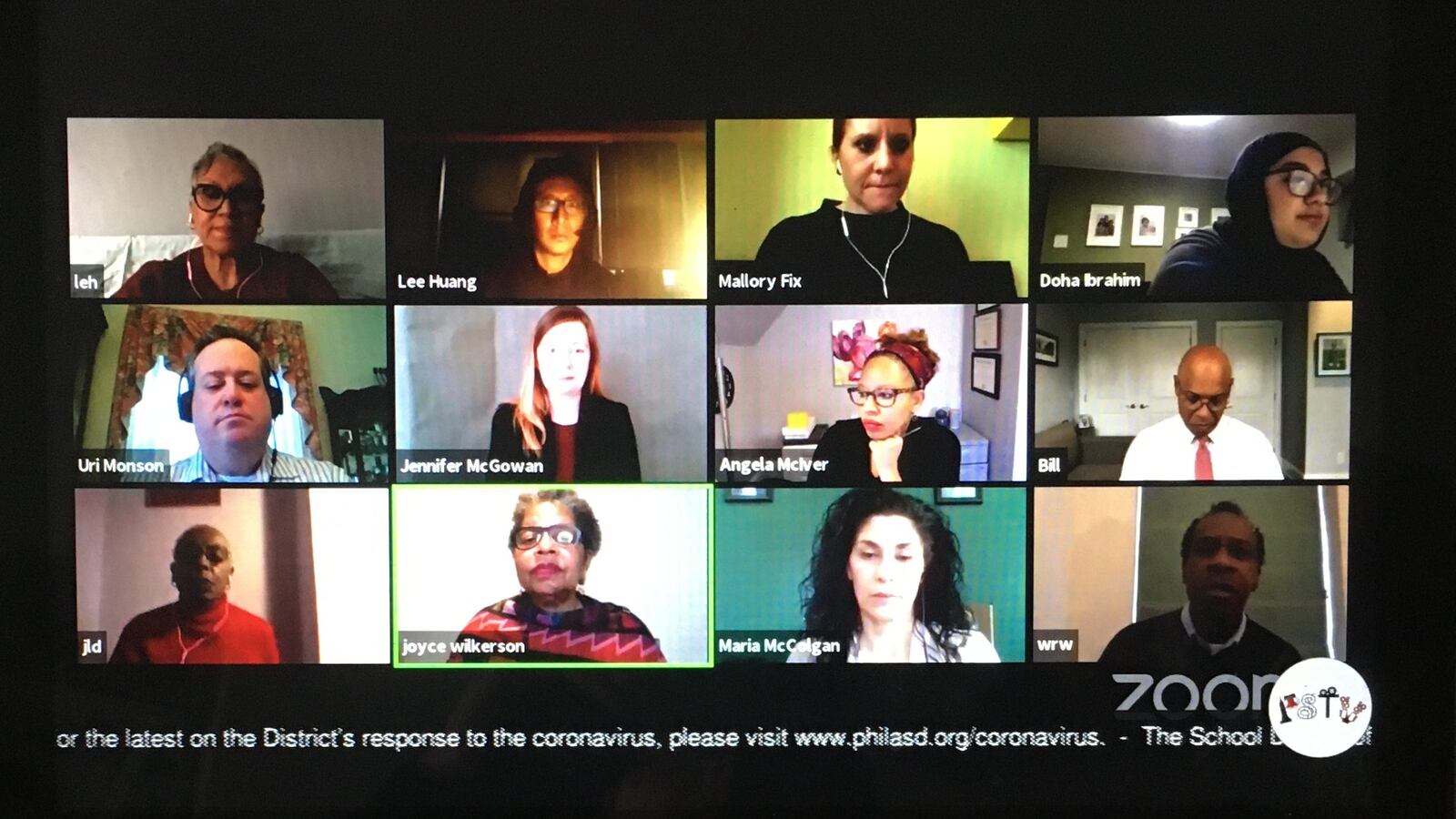

During Thursday’s hearing, conducted virtually over Zoom and streamed live over the internet and public access channels, officials laid out a raft of unpleasant fiscal projections based on the economic shutdown that the pandemic has triggered. This year’s District budget took a modest hit but is still in the black, they said. But next year’s budget gap could approach $40 million, officials said, and within five years, the District could face a shortfall of as much as a billion dollars.

The looming revenue shortfall could undermine not just the District’s finances but also its fragile gains in academics, staffing levels, and school climate, officials said.

“This is not just about a budget, dollars and cents,” said Board President Joyce Wilkerson. “There are real children’s futures on the line.”

The depth of the fiscal damage to the District will depend in part on whether Pennsylvania legislators choose to maintain the state’s own financial efforts and resist the temptation to use federal education stimulus dollars for state deficit reduction, board members said.

In theory, federal stimulus dollars are meant to supplement state spending, keeping school district budgets at their historic levels even as state revenues fall. But the stimulus law passed in March allows states to use the federal dollars to replace state spending, with the approval of a waiver by the federal Department of Education.

Such a move means lawmakers can balance state budgets, but leaves school districts without new revenues, forcing them to either cut spending or run deficits of their own.

Board asks residents to lobby

During Thursday’s hearing, board members called on Philadelphia residents to immediately start lobbying state officials to use stimulus dollars to “supplement, not supplant” state spending.

“Our public schools have made tremendous strides. … We cannot afford to take steps back,” said student board member Doha Ibrahim, a senior at Lincoln High.

Ibrahim said that she remembers well the hallmarks of the District’s austerity years under Republican Gov. Tom Corbett, who served from 2011 to 2014: crowded classrooms, deferred maintenance, and schools struggling to provide even the most basic supports. Corbett took office just as two years of post-2008 stimulus money ran out; Pennsylvania had used that money to replace its own spending, and when it disappeared, Corbett made no effort to fill the gap. As a result, state aid to districts plummeted, and to make ends meet, Philadelphia took steps that included laying off all school nurses and counselors.

Students citywide felt the pain of those cuts, Ibrahim said, and she urged the board to avoid repeating those lean years at all costs.

“We have spent much of our time in classrooms with too many students … under leaky roofs,” Ibrahim said. “Honor the class of 2020 by safeguarding the education of all future classes. … Tell them not to send our schools backwards.”

Board members echoed the point. “We need that state money as promised,” said board member Mallory Fix-Lopez.

Board member Julia Danzy urged “every person in Philadelphia” to tell state officials to maintain their education spending.

“If we do not raise our voices now, the financial impact of the coronavirus crisis will be devastating to public education in Philadelphia. We have already lived through this, and we can’t afford to do it again,” said Danzy.

“Our state officials cannot be allowed to use these [federal stimulus] dollars to replace state spending,” she said.

CARES Act stimulus

Right now, under the stimulus bill known as the CARES Act, Pennsylvania is in line to receive more than $524 million in federal K-12 education stimulus funds. It also includes $104 million from the Governor’s Emergency Education Relief Fund, which can be used at all education levels.

The CARES Act calls for those funds to be distributed to school districts statewide by formula, based on a mix of demographics and historic spending. Philadelphia is due for at least $116 million of that money.

But although the CARES Act nominally requires states to maintain their own spending, it also includes a critical clause allowing states to reduce it. Under this act, any state with a “precipitous decline in financial resources” – a category that in 2021 will surely include all 50 states – can apply to the U.S. Department of Education for a waiver that relieves it of any obligation to maintain state financial efforts.

Whether Pennsylvania will seek such a waiver is unclear, District officials and advocates said. Chief Financial Officer Uri Monson said the District had reached out to Harrisburg repeatedly but had failed to get a clear sense of the state’s plans for handling fiscal issues.

“We made several attempts to find out,” Monson said. “We’re on our own.”

But local advocates, mindful of Pennsylvania Republicans’ reaction to the 2008 recession, are girding for battle.

Under GOP leadership, the state’s response to the 2008 economic slowdown was to cut taxes and slash spending on education of all kinds. Reynelle Brown Staley of the Education Law Center said her group believes that the austerity-driven strategies of the Corbett years should not be repeated.

“We definitely do not want to repeat the mistakes of the last recession, when federal funds were used to supplant state aid and education funding was slashed for every district across the state,” said Staley. “It took nearly a full decade to recover from those cuts.”

Staley said ELC will be pushing to stop Pennsylvania from using federal dollars to reduce its own spending.

“We want to ensure that Pennsylvania does not request such a waiver,” Staley said in a statement. “The state and the federal government should be combining their resources so that more money – not less – is available to under-resourced school districts.”

National advocates are taking a similar tack. A coalition of major organizations brought together under the banner of the National Education Association – including heavy hitters representing teachers, principals, and superintendents – has been calling for an additional $200 billion in federal education stimulus. The coalition is worried by the CARES Act’s lack of what are known as “maintenance of effort” protections.

Among the NEA’s requests: “Any [new] funding must include strict protections related to ‘supplement, not supplant’ and ensure that a high percentage … end up at the local level.”

After Thursday’s budget hearing, City Councilwoman Helen Gym released a statement vowing to avoid a repeat of the Corbett years.

“Following the Great Recession, school districts across the Commonwealth suffered drastic and draconian cuts,” Gym wrote. This time around, the pandemic’s “inevitable” budget impact “must not compromise the strides we have made. Any state budget that does not fully fund each and every district is unacceptable.”

And earlier this week, a statewide coalition of dozens of advocacy groups and educators’ organizations, including the League of Women Voters, the Pennsylvania Association of Rural and Small Schools, the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers, and the Urban League of Philadelphia issued a letter to Pennsylvania’s congressional delegation, endorsing the NEA’s call for a major new education stimulus package.

“A $200 billion emergency response for K-12 schools, as recently recommended by a coalition of national educational organizations, is critical,” said the letter, co-authored by the Education Law Center.

“The COVID-19 school closures revealed the inequities in the state’s education system, as some districts have been able to transition to full online instruction seamlessly, while other districts lack the resources to do so,” the group wrote. “These inequities will only worsen without a strong federal response.”

Growing deficits expected

The short-term impact of the coronavirus shutdown on the current District budget appears relatively modest so far, officials said. The shutdown has reduced some 2019-20 revenue, but also some costs, such as those of cleaning buildings or transporting students.

Some additional revenue information for the current fiscal year is still forthcoming, Monson said, including estimates of this year’s city school tax revenue.

But for now, Monson said, the District anticipates losing about $64 million in 2019-20 revenue, mostly from lost business taxes. But it also anticipates saving about $51 million in costs. Overall, Monson said the District expects to end the 2019-20 budget year with about $13.2 million less than expected, but with a healthy fund balance of about $140 million.

From there, projected deficits rise steeply, with costs increasing and tax revenues expected to decline dramatically for the city and state alike as a result of the pandemic. Monson said the District’s budget gap could be $38 million in 2020-21, $240 million the year after that, and $1 billion by 2025.

That’s in sharp contrast with the District’s pre-corona fiscal outlook, which as recently as March – “one brief, shining moment,” Monson said ruefully – anticipated surpluses around $160 million in each of the next five years.

Hite said that his message to Harrisburg will be that it is essential to protect “the financial stability we’ve created.” When Hite arrived in 2012, the District was already in a fiscal crisis triggered by Gov. Corbett’s 2011 budget cuts, which took $1 billion out of K-12 public education statewide. Philadelphia absorbed about a quarter of that hit.

This time around, Hite said, District supporters can try to stop the looming financial crisis before it forces the District to make painful cuts to academic programs or student supports.

“We’re still in a space to advocate before making lots of hard decisions,” Hite said.

District officials have a few modest options for saving revenue, such as looking for ways to take advantage of the current low oil prices, Monson said. He said the District is reviewing all manner of contracts and spending plans to determine what’s “mission critical” and what can be cut.

But the District will also be facing new and rising costs in other areas.

“Our two largest labor contracts expire in August,” Monson said; negotiations are underway with the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers and the Service Employees International Union 32BJ, but their new deals are on the list of unknown costs ahead.

To fill gaps, member Angela McIver called on the board to explore “non-traditional” revenues, such as requiring major nonprofits to make the large “payments in lieu of taxes” known as PILOTS. About $794 million in Philadelphia real estate is exempt from property taxes by virtue of being owned by nonprofits, including universities and government. For years, local advocates – including, at times, Mayor Kenney – have argued that these organizations should pay more, but without success.

McIver said the board should consider putting its shoulder to that wheel.

“I would love to encourage the District and the board to have really open conversation with the community [about revenue],” McIver said. “We may be thinking very narrowly about how we move forward …. PILOTS should be put back on the table.”

But the biggest financial boost for the state and the District alike, officials and advocates say, would be more federal stimulus.

Additional stimulus is being debated in Washington, D.C., as are various adjustments to statutory requirements for special education spending and career and technical training. But so far, the total amount of education stimulus provided nationwide is $13.5 billion, a fraction of the $79 billion in education stimulus provided by the Obama administration in 2009.

ELC’s Staley said that the state and its school districts deserve a stimulus plan that fully addresses student and school district needs and doesn’t force administrators to make painful budget cuts in the name of austerity.

“The one sure way of preventing [a fiscal disaster] is with a robust Phase 4 package of aid to states and to schools from the federal government,” Staley said. “We and our allies have been urging Pennsylvania’s elected officials to send a unified message to Washington that a larger round of federal aid is desperately needed to ensure students don’t suffer immeasurable losses.”

Contention over charter costs

After the budget hearing, the board held a joint meeting of its committees on academics and on facilities and operations to preview and discuss items that it will vote on April 30.

On the agenda for next week are votes on the renewals of six charter schools and the relocation of another. But the board has also scheduled a resolution that calls for an overhaul in state charter funding, saying that the current formula “requires districts to send more money to charter schools than is needed to operate their programs.”

Before the pandemic hit, there was a growing statewide movement among districts seeking charter funding reform, and many school boards had adopted such resolutions. Gov. Wolf laid out a charter reform agenda last summer that included a formula overhaul and backed it up in his budget address in February.

Monson’s pre-pandemic budget assumptions for the next five years were that Wolf’s proposal would be adopted, which helped account for his prediction of robust ongoing fund balances for the next five years.

Such a massive change in the charter law was always a long shot in the Republican-dominated state legislature, but the pandemic-induced crisis has pretty much pulled any hope for action on that issue off the table. Monson’s new projections assume that the Wolf administration’s attempts at charter reform will not succeed and that charter payments, particularly for special education, will continue to rise.

Reflecting the acrimony over this issue – with charters and districts fighting over inadequate education dollars – Laurada Byers, founder of the Russell Byers Charter School, urged the board to drop the resolution.

“I urge you to immediately withdraw this resolution,” she said. “In this moment of unprecedented pain and calamity, it is inappropriate and absurd that the school board of Philadelphia would propose on its agenda the passage of this divisive resolution.”

Board member Maria McColgan, whose children attend charter schools, had urged that the resolution be toned down.

“I agree there are major issues with the law … but we don’t need inflammatory language,” she said.

Amid the controversy and the crisis, the board plans to vote on the futures of six charter schools at its April 30 meeting.

The Charter Schools Office is recommending five-year renewals, with conditions, of Northwood Academy, Community Academy, Imhotep Academy, and People for People Charter School. It is recommending that the board not renew two schools run by Universal Companies – Universal Daroff and Universal Bluford.

Christina Grant, head of the CSO, said that Community and Northwood mostly met or approached academic standards, as well as metrics for organization and financial stability. Imhotep, she said, which the board granted a one-year extension in 2019 to turn itself around, has done well since it was taken over by the Sankofa Management Team.

Citing low academic achievement, it wants People for People to drop its high school and operate as a K-8 school.

The two Universal schools, Grant said, suffer from inconsistent academics and myriad operational and fiscal problems.

The charter office has recommended nonrenewals for other Universal schools as far back as 2016, including Vare Middle and Audenried High schools. But they remain open.

UPDATE On Friday, Universal issued a statement about the nonrenewal recommendations, saying it didn’t receive the recommendations before they were made public and calling them “inequitable.”

“We will address and defend vigorously our academic growth and improvement, organizational structure and stability as an Education Management Organization against the Charter’s office recommendation for Universal Bluford and Universal Daroff.” END UPDATE The office is also recommending approval of a proposed relocation of the Laboratory Charter School from three sites in Northern Liberties and Overbrook to two locations, one in North Philadelphia and one in East Falls, which would house grades 6-8.

Last year, Lab Charter proposed relocating its entire K-8 operation to East Falls. After stiff opposition from the community, the board decided then to postpone its consideration of the move “indefinitely.”

This new proposal would limit the East Falls campus to grades 6-8, but local residents are still opposed.

Carla Lewandowski told the board that the charter school potentially could pull students from Thomas Mifflin, the neighborhood elementary school, which is under capacity but has been steadily increasing its enrollment. If Lab Charter cuts into that trend, “this can result in stranded costs to the School District of $3.7 million,” Lewandowski said. “Continuing to grow and improve District-managed schools and attracting students back to great schools near where they live would also mitigate these fiscal challenges for the District.”

The Board’s action meeting will take place virtually at 5 p.m next Thursday, April 30.