This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

The Notebook prepared this report on the District’s kindergarten modernization effort for our spring print edition before the full force of the COVID-19 pandemic hit. We have posted the stories from the print edition online over the past week along with updates from the providers and advocates we featured. As far as kindergarten modernization, it is hard to say what will happen with the schedule to add new schools this summer given the crisis. “The plan is to continue with the modernizations in the summer, but if the construction industry isn’t able to provide the resources…it could be that these projects are delayed,” said a District spokeswoman via text. “We are playing it by ear and monitoring as best we can day to day.” Kindergarten registration is proceeding as planned: early registration is open until May 29 for all students who will be 5 years old by Sept. 1.

When kindergarten started in the 2018-19 at Webster Elementary School, the teachers were just as excited as the students — if not more so.

Bernadette O’Brien, a 30-year teaching vet, remembers thinking, “OMG, best thing ever!” as she looked around her refurbished room in Webster’s Little School House, a self-contained, 2001 addition to the 60s-era Port Richmond school.

She looked at the new teal and gray paint on the cinder block walls and the big round tables that have plenty of room and little indents that spaced out the children evenly on their red, blue, and purple chairs. She spied the yellow stools that acted as balance balls for children who might want or need to work on their gross motor skills.

In the center of the teal wall was a huge computer screen, compatible with the new classroom iPads, better and more interactive than the old whiteboard. There was a reading and writing nook full of books, a LEGO station, Play DOH, brightly colored cubbies, bins with blocks and math manipulatives, drawers full of letters attached to key rings, a big white rocking chair next to the reading rug.

All in all, everything a kindergarten teacher could want. The children, too, when they arrived, she said, were wide-eyed with wonder.

Prior to the modernization, O’Brien and other kindergarten teachers, with just $100 a year allotted for supplies, had to buy materials themselves or repurpose their own children’s playthings.

In the old days, “you had to pack up your entire room, everything you own,” said Maria Binck, Webster’s reading specialist. When she was a classroom teacher, “five different times, I had to put it all in a truck and drive it home. I know how expensive it is.”

Over the last several years, the School District of Philadelphia has invested heavily in modernizing its kindergarten through third grade classrooms, part of a concerted push toward improving early literacy across the District. In particular, the goal is to help all students reach the important milestone of reading proficiently by the end of third grade.

The modernizations started in 2017, and cover anywhere between seven and 10 schools a year. So far, 232 classrooms have been upgraded, and when the project is done at the end of the 2020-21 school year, the total will be over 500.

Which schools to prioritize is based on those that have been on the lower end of third grade test scores, and where the buildings are in good enough condition for a new investment.

Besides the modernizations, the District has also adopted a “comprehensive literacy framework,” which offers a checklist and timetable for activities, including in a daily, required two-hour “literacy block” that involves students participating in different reading activities. In addition to the District’s literacy coaches, some schools have coaches from Children’s Literacy Initiative, which specializes in teacher coaching and creating language-rich classrooms.

No mistake, the literacy block is not about the teacher doing “stand and deliver” in front of the classroom, but combines whole group reading with small group and individualized instruction. Some students write, or act out stories with puppets, or curl up in the reading nook with a book color-coded so students can pick out ones appropriate for their level.

“Early literacy goes all the way from birth to third grade,” said Diane Castelbuono, the District’s deputy chief of early learning. “How kids learn can be traced back to early language and brain development in their earliest years.”

That document also undergoes periodic revisions to keep up with the latest research in the science of reading. One is due in time for the next school year.

“I would say in previous iterations, we’ve been probably less focused on phonics and phonemic awareness in the lower grades than we should have been,” said Castelbuono.

Playing and Learning

While doing that, the District has also worked to maintain a healthy balance between maximizing young children’s most effective means of learning — which is play — with activities involving words and letters that are more structured.

“Playing and learning are not separate, ever,” Castelbuono said. “Kindergarten is all about learning through play.”

The idea that there is somehow a conflict between children learning their letters and being able to play is misplaced, she said.

“They are not mutually exclusive things,” she said. “It does make me a little exasperated when we get asked about learning vs. play. They are interrelated. A good kindergarten curriculum will never discount play.”

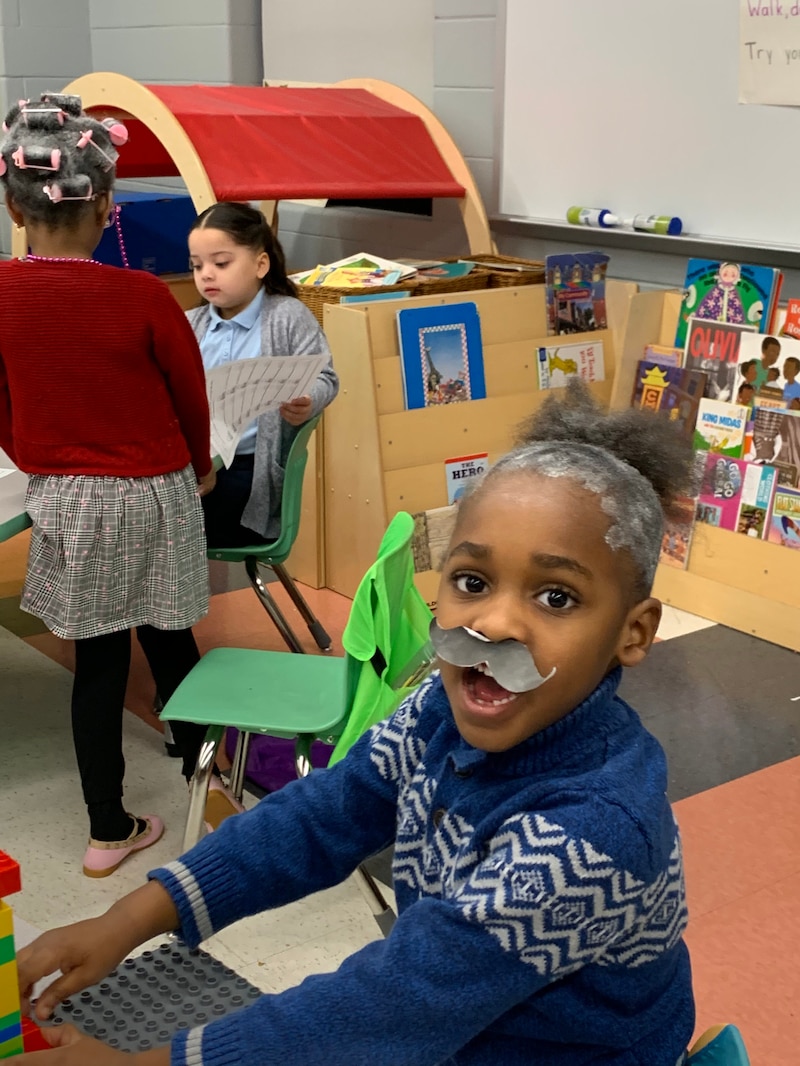

Xavier Hernandez, a kindergarten student in O’Brien’s class, on the 100th day of school. Photo by Dale Mezzacappa.

She points out that the modernized classrooms have arts centers, a puppet stage for acting out stories, and a kitchen area.

There are anxieties, however, that the increasing emphasis on structuring time makes it harder for kindergarten teachers to try out new things and to address the widely varying skill levels in classrooms that can have as many as 30 children. For instance, while writing — and its precursor, drawing — is part of the framework, it can be given short shrift.

O’Brien, for instance, said that “it’s definitely going in the direction of more academic vs. traditional play, like the housekeeping centers used to be. “Personally, I’m a little sad there isn’t as much playing with dolls and in the kitchen.”

She isn’t really complaining, though. “I can incorporate it in other ways. In the reading tent, they can role-play. I’ve learned to adapt, and the kids are enjoying it and benefiting from it. In math and literacy, they are more advanced than they ever were.

“They think everything is play. It hasn’t hurt them.”

And while adults might want to draw a sharp line between activities that specifically promote reading and writing, for the kids the line is pretty blurry, especially in the hands of a skilled teacher with the latest in equipment and materials, working in a cheerful room.

In the LEGO center, they are learning about characters; they have cards depicting settings, like a farm, on which to arrange their people and animals. “It’s not like the traditional activities that we did, but it’s great, and they are learning so many things,” O’Brien said.

One of Webster’s other veteran kindergarten teachers, Kayla Gusst, has been doing this for 29 years. The modernization, she said, “is amazing, it gave us so many good things.” She especially praises the extensive professional development for the teachers, offered after school and on some Saturdays, organized by Paula Sahm, educational facilities planner in the Office of Childhood Education.

Gusst said at the trainings, teachers come from “all over the city” to share ideas. “I’ve been thrilled,” she said, especially at the Saturday book club, in which they study the latest literature on reading best practices and discuss classroom issues and strategies.

The iPads connect to the new smart board, and Gusst can project and underline words and letters for emphasis. Before, she would have students crowd around her iPad; now all the students have access to their own.

Gusst loves it. “I learned a whole new way of using technology at the Apple store,” she said.

Like O’Brien, she is a little nostalgic for some of the traditional practices and says that the District is definitely pushing kindergarten in a more academic direction. Still, “The reading center, the listening center, the writing center, they absolutely love,” she said. “Everything is beautiful, the children love it and are happy to be in such a beautiful environment.”

She adds with a wink, “Not that my room was so bad before.”

O’Brien added that the best thing that happened in Webster was principal Sherri Arabia’s decision to use discretionary funds in the school’s budget to hire an extra kindergarten teacher and reduce class size to 20.

The smaller class size allows her to spend more time with students in small groups and individually to discern their strengths and weaknesses. Plus, she said, behavior is better with 20 rather than 30 students.

“That’s the most beneficial thing,” she said. “We have five kindergartens this year. Last year, there were four. Now I can help more kids, it’s beautiful. I pray it continues.”

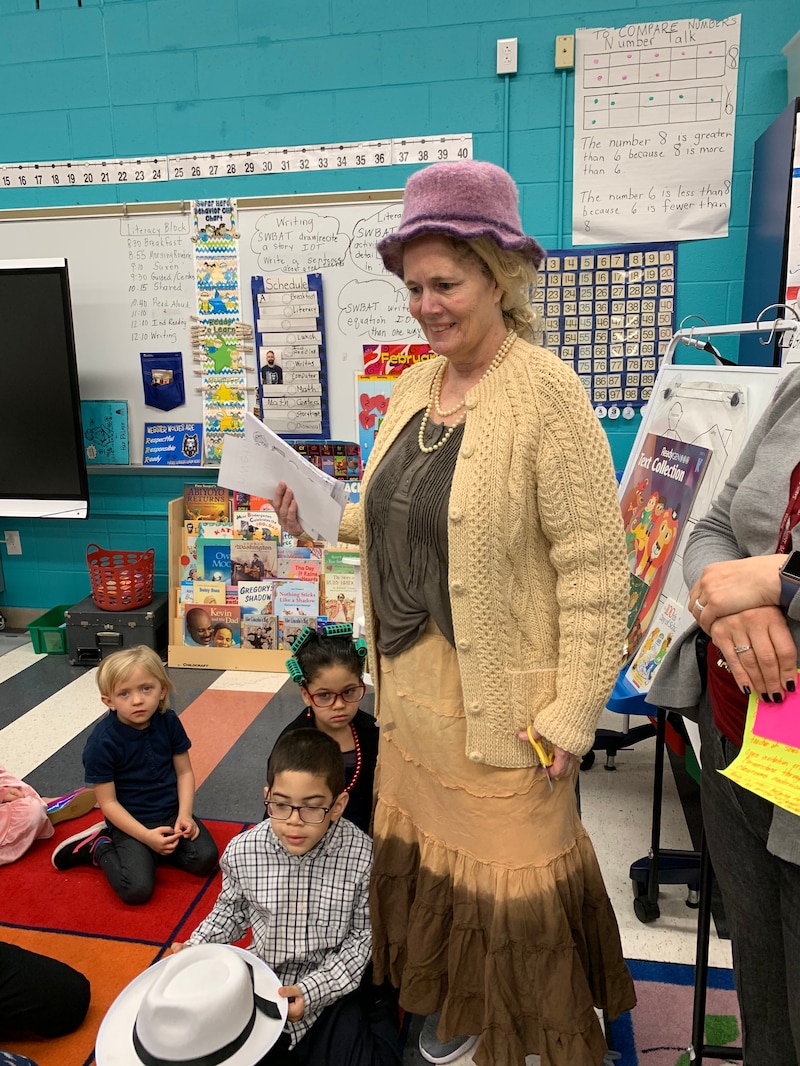

Webster teacher Bernadette O’Brien on the 100th day of school. Photo by Dale Mezzacappa

On Feb. 11, Webster students and those across the District were celebrating the 100th day of school, and many of them dressed up as if they were 100 years old. They also, with help from parents or guardians, made posters with 100 items on it.

Jeremy Hernandez’s mom helped him with a poster that had 100 fake coins along with Mario and goombas from the Mario Bros. video game. Jeremy, who was wearing a paper moustache and had gray in his hair, said his mom came up with the idea.

Jayden DiGiorgio was proud of his poster, which had 40 cupcakes and 100 beads that formed the number “100.”

“I helped cut out the cupcakes,” he boasted, while eyeing Jeremy’s poster, displayed next to his. “I like this one,” he said, adding “those coins are fake.”

Parents were clearly involved in making the posters. Binck said that not many of Webster’s parents have books at home, but that the student iPads include apps on which they can download books for when they are in the reading center. If parents have devices at home, they can also use the apps.

“They are able to get that reader, and the child at home reads with the parent,” she said.

In addition, there are professional development sessions for parents as well; each school decides how to do it.

At Webster, they are made available once a month. “As a reading teacher, it’s imperative to do that,” Binck said. “We’ve tried to be strategic when we have them.” They hold “student of the month” celebrations for all who meet certain criteria, “and when parents show up, I hold them captive and have a parent workshop. We keep it short and sweet, 30 minutes.”

Waiting for upgrades

There is not quite a world of difference at Pollock School about seven miles up Rte 95. But it is different. Helena Griffin’s classroom at Pollock hasn’t had its makeover yet — it is due to happen over the summer, in time for next year.

Pollock’s kindergartens are in trailers, older and more primitive versions of the Little School Houses that now sit in several school parking lots in areas that needed more space. Griffin is in her ninth year teaching kindergarten. She also taught first grade, second grade and sixth grade, and when she started out as a literacy intern, she was in third grade. All but the first few months of her tenure in the District has been at Pollock.

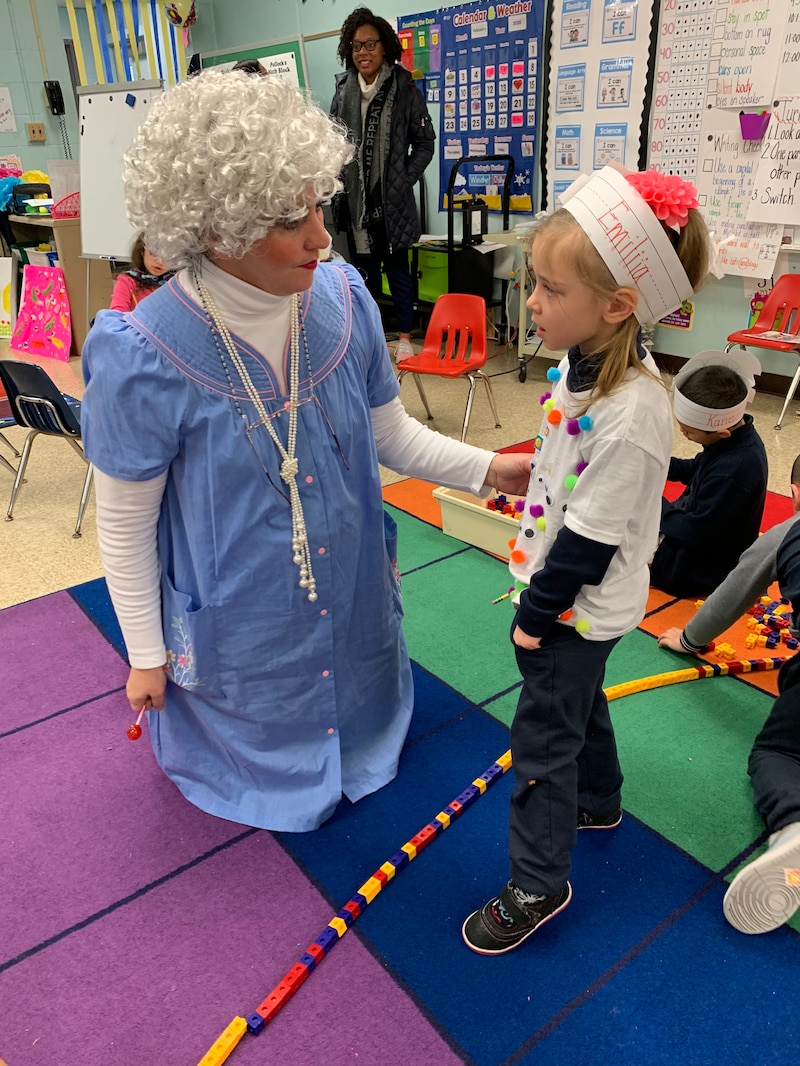

Pollock kindergarten teacher Amanda Kane on the 100th day of school. Photo by Dale Mezzacappa.

During the 100 day celebration, some of her students were counting 100 beads onto a string. Two boys were putting number cards in order from 1 to 100. She looked at their work. They were doing fine until 13, but then put 41 and 51 instead of 14 and 15. “Look to see which number comes first, “ she prodded gently. They quickly realized their mistake, and it was easy from there.

In the room, there were tables with 100 cups, 100 LEGOs, 100 fruit loops. She asked them to write something about how they are 100 days smarter since they started school.

The big difference from Webster: just about everything in this room, except for the furniture, she bought herself, spending way more than the $100 annual allotment for supplies. The LEGOs that two boys are carefully stacking 100 bricks high (or long) were once her own children’s. There is a smart board, but not one hooked up to iPads and projectors where she can draw and write on it, and manipulate different software programs, and where the kids can do it also.

Instead, two ancient iMacs sit unused in one corner of the room. With children who are accustomed to smart phones and tablets, the desktops might as well be papyrus and quills.

When asked about the impending updates to her classroom, she said, “I’m thrilled. I have chills thinking about it. It’s a lot to keep five-year-olds engaged.”

With the new smart board and individual iPads, she noted, she will be able to prepare lessons at home.

At the same time, Griffin thinks it is fine to use explicit lessons to teach reading and spend a lot of time on activities like cutting out and coloring letters and words. “We still need to work on phonics skills,” she said. “I feel like if they learn to read before they leave here, they’re going to be successful. If they know their letters and sounds, they’ll be more successful than if they did not.”

She is looking forward to how the iPads and interactive smart board will help with math skills. But she is also looking forward to the puppet center and the center for dramatic play.

“I can’t wait to go to professional development to get started,” she said — which will be in March for teachers like her whose classrooms are due for makeovers over the summer.

Regardless, all the students looked to be enjoying themselves. She and the other teachers all mentioned Fun Fridays, when the kids can pick their center and “relax” with their friends.

Over the years, she said, different leaders had different emphases, and under some, “We weren’t allowed to do certain things.” When schedules were rigid, 10 minutes for this, five for that, “it was really hard, the kids were engaged, and you’d say, time’s up, sometimes you needed five minutes more.”

Now, she said, the curriculum is still structured, there are timelines, there are literacy and math blocks, as well as established times for science and social studies. “There’s so much packed in a day,” she said.

But there are also “brain breaks” and exercise and singing. The blocks are longer, with 20 minutes shared reading, 30 minutes writing, for example. The 100 day celebration was a lot about math, but it also provided some freedom and a lot of fun.

“I feel that children are more engaged when they have time to incorporate play into the centers,” said Griffin. “I had a kitchen center, it was also a literacy center. They had menus and grocery store fliers and took food orders. They were playing, and they were learning, reading print and writing.”

Amanda Kane leads the other kindergarten located in the portable space. It’s her third year teaching at that level. She has also taught “every other grade” through eighth, she said.

“This is where I’m meant to be,” she said. “It’s where you see the biggest growth. They are so eager. When they get to play, they are able to naturally learn certain skills, like social-emotional ones, how to share, how to work together. Instead of me telling them, they learn together.

“I think they’re able to learn more if they express themselves through play. They build a tower of blocks, a parking structure, and apartment building, they can talk about where they live,

Does she like the literacy blocks? “I feel, sometimes, we work to put pressure on kids in a certain way, and it hinders their ability to come to their own way of learning.” It’s better, she said, that “they come to their own conclusions instead of us telling them what to learn.”

The 100 day projects, for example, were a big learning experience as well as a way to involve parents. Some of the projects “were so good that they asked if they could clap for their classmates. “I said, ‘of course you can clap.’”

As far as the updated classroom, “I cannot wait. I have been in the school district 17 years and to have a modernized classroom blows my mind. I think it will help students learn when they see new things, and feel our own excitement. We’ll be able to open things up to them and they’ll share in the excitement. Even if we’re just getting an interactive smartboard. But we’re getting new tables, chairs, manipulatives…it’s a new day.”