This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

Elizabeth Taylor, a Masterman High School social studies teacher, had a lot planned before COVID-19 wiped out in-person schooling for the rest of the academic year.

She was about to start the Harlem Renaissance unit in her African American history class. Every year, she looks forward to one specific day in that class. She sets up stations around the classroom as art galleries, literary salons, and clubs, and students get to traverse those stations as if they’re living in the Harlem Renaissance — they read short stories from the time, listen to music, and view the art.

“It’s an academic exercise, but it’s fun to have students move around,” Taylor said.

Those kinds of activities grow out of one of Taylor’s core beliefs: that “learning is building knowledge through experiences.”

“But we just can’t have those same experiences now that classes are online,” she said.

Classes have technically been online for almost two months now, since school buildings closed March 13 due to the coronavirus pandemic. But Monday marked a turning point in Philadelphia’s online learning — grading began and, for the first time since early March, teachers introduced new material to students.

On March 30, the District unveiled a 10-page, four-phase plan for teachers to acclimate themselves and their students to this new reality. The first three phases involved optional virtual classes for students, as teachers learned how to navigate Zoom, Google Meet, and Google Classroom — tools for videoconferencing and delivering online assignments.

The fourth and final phase of the District’s plan, which began Monday, mandates that students attend class, though the consequences of not doing so remain unclear.

Based on several interviews Monday, this phase — when attendance and work start to count — has met with a mixed reception and some continued confusion. Most students have class from around 9 a.m. to noon each day, and teachers hold office hours in the afternoon. To log their attendance each school day, students must log in to a portal on the School District website and mark themselves present for each class.

But on Monday morning, students such as Nutsa Abashidze, a sophomore at Central High School, were already having trouble with philasd.org. Abashidze reported that when she tried to log her attendance for Monday’s classes, the website crashed, and she spoke to many other students who experienced the same problem.

“I think there were just too many people on the website at once, and it was overloaded,” Abashidze said. “I feel like someone should have seen this coming. … I hope attendance isn’t counted today.”

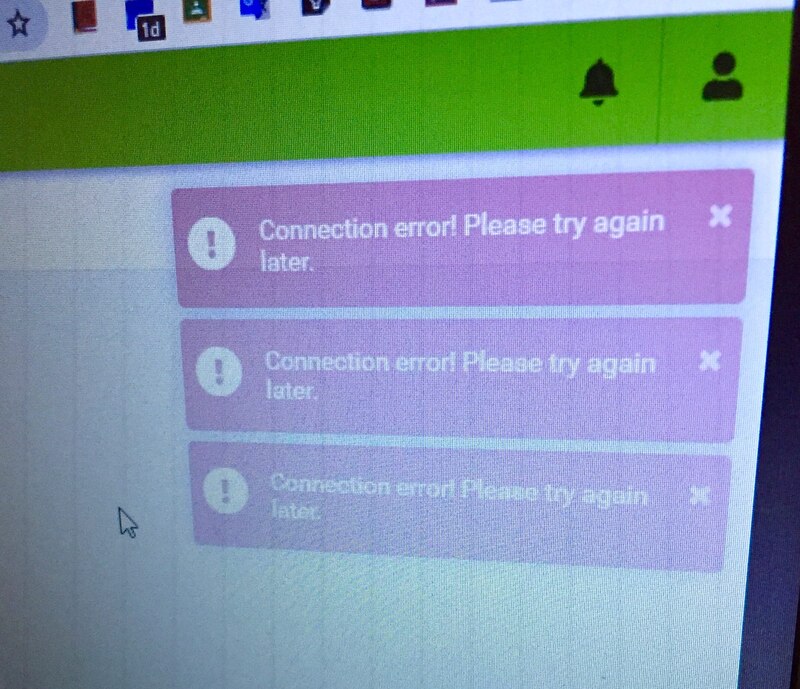

The message on many screens at peak time for logging in to the School District site Monday morning.

Abashidze said teachers at Central didn’t say how they would handle Monday’s gaps in attendance caused by the website crashing.

Jessica Brown, the principal of Masterman, did say in an email to students on Monday that teachers would record students’ attendance if they weren’t able to log it on the District website.

(Megan Lello of the District’s communications office said that there is no plan now to change the process, but that officials and the vendor who assists with the Infinite Classroom system would be watching closely to see what happens Tuesday.)

Isabel Portner, a sophomore at Masterman High School, had no trouble logging her attendance for the day, but she said there was occasional trouble with her teachers’ WiFi connection. Sometimes, a teacher would ask a question on Google Meet, and it might take up to a minute for a student to respond.

“For some teachers, the WiFi is choppy,” Portner said. “I think it makes the class less engaging sometimes.”

But despite the obstacles, Portner and Abashidze said they both find a definite upside to online class vs. in-person class. For one thing, they don’t have to worry about travel time to school.

“I have an hour commute each way,” Abashidze, who’s from West Philly, said. “You also only have class for a few hours a day, and I’ve had time to relax in between. It’s definitely less stressful.”

Confusion over grading

Students have been receiving conflicting information about how grading will work.

Superintendent William Hite has said he doesn’t want students to be negatively impacted because of their circumstances and is following a philosophy of “do no harm.” He doesn’t want students’ grades to go down because they can’t get online or because they must get a job to make ends meet during the pandemic.

Brown said the same thing in an email to the student body.

“Students will not be penalized for attendance problems or given a zero for not completing an assignment,” she said. “However, students can improve their GPA.”

Portner and Abashidze’s teachers have largely echoed that message. Portner said that all of her teachers told her that when grading resumed on Monday, her grades could only go up, not down.

“That’s nice,” Portner said. “It takes a lot of the stress off.”

But she said she’s still confused about some aspects of the District’s policy.

“What if someone just chooses not to show up [to class] for the rest of the year? Will they be punished for that?” Portner asked. “Also, what if I fail a test? Is that not gonna make my grade go down at all?”

District spokesperson Monica Lewis told the Notebook in April that students can still face consequences if they choose not to show up for the rest of the year.

“If they had an A or a B average on March 13, when the schools closed, and then decided to do no digital learning from now through June, their grade average could decline,” Lewis said. “It is possible to fail for the year if they don’t do work for the third marking period.”

Lewis added that students who don’t complete the work will be evaluated by their teachers on a case-by-case basis to determine whether they are excused because of hardship. Still, it’s unclear how much of a student’s grade would be affected by a failing test grade, or whether just attending class and doing the work guarantees a pass for the year.

Hite said the District is still working through this — whether to base grades largely on participation or on the quality of work.

In his weekly phone call with reporters on April 30, he said the District was considering how to grade. Grades could be based “simply on participation, making sure assignments are completed,” rather than on the quality of the content. “The goal is to keep students engaged; we want to introduce new material, but also reduce the regression that is likely to occur if students are doing nothing.”

The goal, he said, “is to create a positive situation for students and not be punitive.”

Some parents have expressed concern that students will lose motivation if their grades can’t go down during online school. Portner and Abashidze insist that’s not the case.

“I want to bring my grades up, and I’m glad I have the opportunity to do that now,” Abashidze said.

“Masterman’s a stressful environment,” Portner said. “Anytime you take away stress, it helps us learn better.”

Communication conflict

With circumstances constantly evolving in the era of COVID-19, especially for closed schools, some important information has slipped through the cracks, students say.

Some Masterman students felt that they were not kept up-to-date on the latest District policies. They said the information they had received from everyone above their teachers has been vague. They feel they were not made to fully understand how they’re supposed to approach online school or how they’re going to be graded.

Portner said she wasn’t informed until Sunday night that students had to log in to the School District website to fill in their attendance. She said she’s not sure whose job it is to disseminate that kind of information, but she should have been informed about that a lot earlier.

“If [attendance] is counted now, that’s kind of important,” Portner said.

Masterman principal Brown said, via email, that she didn’t specify that students should log in by 10 a.m. each day until a day or two before Monday. She didn’t offer a reason why, but she said it’s not a District requirement.

Brown added that she tries “to connect with [her] community about two to three times per week.” She said she sent students robocalls last week to remind them about the beginning of attendance and grading. She also sent The Notebook a couple of examples of reminder emails she sent out to the student body last week about grading and attendance.

Brown and Taylor both say the messaging from the School District has been clear. Taylor said she gets daily emails from officials, and faculty have weekly meetings to iron out any difficulties with online teaching. She thinks the conflicting messages students are receiving are likely due to the constantly changing situation.

“This has been such a difficult time, with people sick and losing their jobs, that I really appreciate people in our school community and District trying to reach out and be flexible and understanding,” Taylor said. “I hope this can be over soon so we can see our students’ faces again. I really miss them.”

Neena Hagen, a Notebook intern, is a student at the University of Pittsburgh and graduated from Philadelphia public schools.