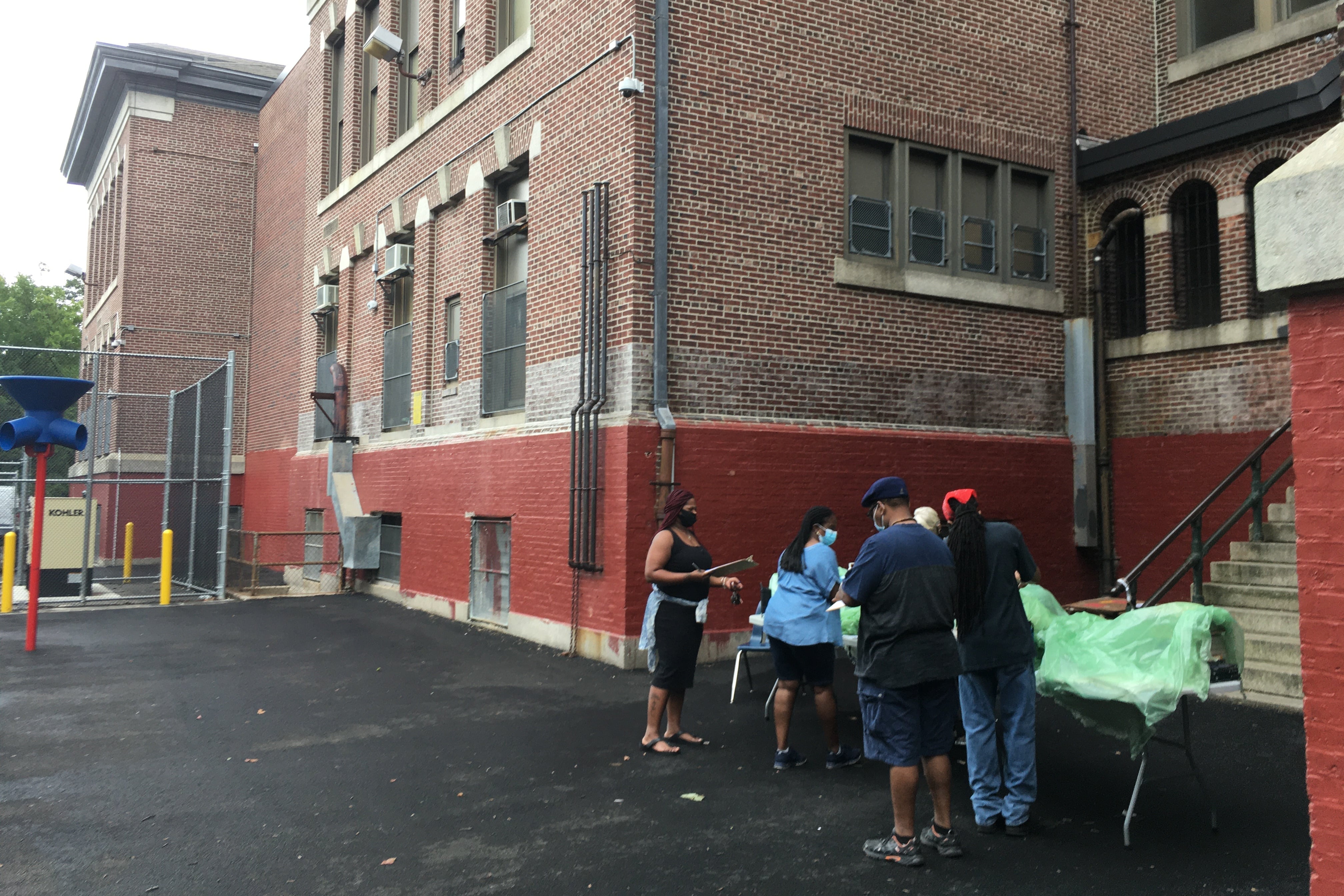

On the eve of the official start of school, parents and students arrived at C.W. Henry School in Mt. Airy to pick up books and supplies for the coming year.

The theme of the day: Making the best of a bad situation.

Eighth-grader Micah Kearney-Lester isn’t thrilled that summer’s over, but he’s not too concerned about having to start school online.

“It doesn’t matter to me. I don’t really like being at school that much,” he said as he stood outside Henry on Tuesday with a bag full of workbooks.

Kearney-Lester’s mother says she is uneasy about him starting a new school year online, but she likes what she has seen so far. As disrupted as the spring semester’s emergency shift to online learning was, said Andrea Kearney, “I saw him become a more independent student. More hands-on.”

She hopes virtual learning might accelerate students’ engagement with technology they’ll rely on for years to come.

“It’s a 21st century moment,” she said.

That same mixture of unease and hope hangs over Philadelphia, where the school year opens Wednesday with all-virtual instruction. Teachers and parents expressed lingering concerns over the quality of online learning, how to make it accessible for all children, and whether buildings will be ready for a return to the classroom later in the fall.

Officials originally wanted to begin the year with a hybrid plan, but postponed in-person learning until at least mid-November after a clamor from teachers and parents that it would not be safe.

That left principals across the city scrambling to plan for virtual learning even as they began preparing buildings. Robin Cooper, head of the Commonwealth Association of School Administrators, said that her members “taught themselves what was needed for their teachers and their students. Never have I been more proud to be president of this resilient group.”

The Philadelphia Federation of Teachers met Monday night, just hours before its current contract expired and agreed to extend negotiations for two weeks so the union and district could agree on a safe reopening plan. PFT President Jerry Jordan said that the district was tying negotiations on wages to such an agreement, which he called “forcing my members to choose between modest increases and their lives.”

He had asked for a one-year contract extension with “modest” raises in base pay, which “acknowledges the enormous challenges of COVID, and aligns with what other cities have done,” he said. He said the union wants more clarity on conditions before his members go back to work in buildings. “Negotiations are far from complete” but an accord is “doable,” he said.

Another lingering concern is the number of students who won’t be able to get online. With students expected to log on by 8:30 a.m. Wednesday, city and district officials say that there are still thousands of households without reliable internet access. They can’t yet say how many signed up for the new PHLConnectED program, launched in August to expand broadband access for students.

“We are using various tactics to engage parents,” said Mark Wheeler, the city’s chief information officer, who said there would be an update next week.

Meanwhile, students as young as kindergarten are being expected to engage via computer for hours each day. The city is opening dozens of “access centers” for K-6 students whose parents or guardians work outside the home and cannot afford child care. Students at the locations can be supervised during the school day and connect to the internet. The buildings, mostly recreation centers, are being rewired to accommodate more robust connections, Wheeler said.

On Sept. 8, 32 centers will open, with others set to start Sept. 21. Each center will have one or two cohorts of 22 students. Officials said that so far 1,147 interest forms have been completed, and 920 students are eligible.

Teachers and principals have been working all summer to solve other problems and to stay connected with students. The outreach to families has helped form closer bonds, said Stephanie Andrewlevich, principal of Mitchell Elementary School in South Philadelphia.

“No one would choose this,” she said, but finding out a parent works nights “gives us a new way to connect,” she said.

Some high schools held virtual freshman orientations, including Paul Robeson in West Philadelphia.

“Communication is a game changer for students and parents experiencing anxiety,” said Robeson Principal Richard Gordon. “We have to react ourselves to be learners in this virtual space.”

Jessica Morris, a third-grade teacher at Andrew Jackson Elementary School, lives in the neighborhood and said she has been visiting her students’ homes. Students have also been visiting her.

“I would be so relieved to get back into the classroom with my students,” she said. “That feels almost like a fantasy right now. But it’s something I want very much, and I hope it can happen in a safe way.”

At Henry on Tuesday morning, as staff handed out workbooks and children played on the nearby jungle gym, a consistent theme was that while the district’s all-online reopening may be less than ideal, it’s better than risking exposure to COVID-19. Parents hope this fall’s online academic offerings are better than last spring’s.

“I feel really nervous. The end of last year was pretty horrible. I’m hoping they have learned some stuff,” said Faridha Traylor, parent of a Henry student.

Traylor said she’d considered online charter schools and home schooling, but decided to keep her eighth-grade son connected to Henry, where he has relationships and support. She and other parents said the staff and principal worked hard to engage parents, using Facebook meetings and direct outreach to keep them informed.

“My son’s first-grade teacher stopped by our house. Dropped off a trifold with his name, a hook and supplies and a little pencil case and a plastic sleeve he can put his schedule in. Adorable,” said Alison Wear, parent of three Henry students.

But the coming challenges are vivid, Wear said. The quality of this year’s academic offerings remains to be seen. Also unclear is whether the district will be able to successfully prepare buildings for reentry, including keeping them clean.

“Soap in the bathroom — they never have it,” said Kearney-Lester, the Henry eighth-grader.

Above it all hangs the question of social justice, with a rising chorus of support for aggressive anti-racism policies and training. Solving for equity at a diverse school like Henry is “absolutely” essential, Wear said, and the pandemic has raised the stakes.

With the principal focused on day-to-day administration, the school’s parent group has taken the lead on community outreach, Wear said, “helping to facilitate a kind of redistribution of resources — school supplies, [child] care during the day. They’ve done some work to survey parents and find out what they need, or what they have in abundance.”

Perhaps the biggest question for these parents is whether students can maintain the kind of personal relationships with teachers and peers that are critical to learning.

“All three of my children have a teacher that’s familiar to them,” Wear said. “They knew each other … but this incoming class doesn’t have that relationship.”