In more than six years as principal of Martin Luther King High School in Philadelphia, Keisha Wilkins has developed a ritual of sending students off in the afternoon with the same parting words: “I love you, be safe, see you tomorrow.”

But twice in the past year at the 551-student school in Philadelphia’s West Oak Lane neighborhood, students haven’t returned. A junior was found shot to death while attending a vigil for another shooting victim last October. And a junior was found shot in the head on Mother’s Day, sitting in a car around the corner from his grandmother’s house.

“There are some kids that don’t come back the next day,” she said, “and it’s not because they don’t want to come back, but it’s because their life is taken prematurely because they had to make adult decisions as children. It’s very hard for us as a school.”

Philadelphia is experiencing historic levels of gun violence. The city hit a grim record of 499 homicides in 2020, and 2021 could prove deadlier — there were 420 homicides as of Tuesday, an 18% increase over the same period the year before.

The number of teenagers killed has been on the rise. So far this year, 52 homicides have been recorded among people under the age of 18 — the same number as all of 2020. That’s up from 28 in 2019, according to the Philadelphia Police Department.

This reality is taking a toll on schools, which are already reeling from the disruption of the pandemic and now struggle to meet the mental health needs of students who have been shot, lost loved ones, or fear for their own safety.

School leaders find themselves balancing these students’ academic and personal needs. For Wilkins, this means developing a relationship with local police officers, offering weekly grief counseling, and searching for programming to keep students on the right track. But she knows she is facing an uphill battle — she estimates 30 teens and young adults with ties to the school have been murdered during her tenure.

“You can’t normalize violence, can’t normalize grief, but you can at least give some outlet,” she said.

It’s become a familiar routine at MLK high school. The police alert the school that a student is impacted by a shooting, either injured themselves or the relative of a victim, and officers pass along a white paper with details of what happened. That’s when Wilkins and her staff decide how to proceed. They reach out to the family to see what’s needed, perhaps a visit or, in the worst cases, money for burial or a funeral.

And when a student has died, the staff have to consider how to tell his peers. April Lancit, the school’s clinical coordinator, said that involves going to the classrooms and “we just opened up the floor for students and faculty to be able to express how they were feeling about what was going on.”

Twice last school year, staff received word of a student’s murder.

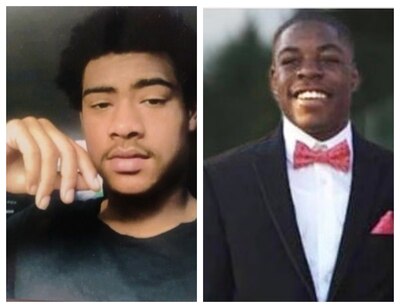

Hyneef Poles was just 17, the same age as Wilkins’ own son. She remembers him as a silly, likeable kid, and a respectful student. He was shot and killed while attending the vigil for another shooting victim. His dad, an MLK alumnus, was himself murdered in 2005, when Hyneef was a boy. “It’s unfortunate that Hyneef died the same way as his Dad,” Wilkins said.

Khalil Burgess, 18, transferred to MLK from a military academy and was in Junior ROTC. He and his twin sister had an unstable home life, staying with relatives, but he was working hard to prepare for graduation. He had gone to his grandmother’s house to wish her a Happy Mother’s Day, Wilkins said, then got in a car with a friend. He and two others in the car were shot to death around the corner.

Both Hyneef and Khalil’s murders remain unsolved.

Lancit, who oversees the school’s STEP program, a districtwide mental health effort, has been holding grief counseling sessions for students affected by gun violence every Thursday. The sessions were held over Zoom and Google Meet last year due to the pandemic but have started up again in person, and Lancit hopes participation will grow from there.

Wilkins said the fact that a grief group is even necessary in high school is “challenging,” but she sees the value for students. “Just a free space for them to actually come in and say, ‘This is what’s going on,’” she said. “’This is how I feel, this is what’s happening in my community and this is the support that I need.’”

Lancit worries about the “toxic stress” her students experience, coming from poor neighborhoods, dealing with violence, facing racism and trauma. “We could go down the list of all types of trauma that they could be experiencing and then they come in and they’re trying to, you know, study and get their academics,” she said. “But they’re also dealing with depression, anxiety, healing from things that they either witnessed or experienced or have been a part of on top of trying to get their education.”

Experts echo Lancit’s concerns about students with post-traumatic stress disorder from experiencing violent events outside school being expected to perform in class. Howard Stevenson, an associate professor in the Graduate School of Education at the University of Pennsylvania, said students could suffer from an inability to focus and remember or they could be hypervigilant in class.

“Thousands of students across Philadelphia are showing up to class traumatized and expected to perform academically,” Stevenson said.

Despite all the school and district are trying to provide, Wilkins and Lancit see areas where the larger community could help these teens. Wilkins believes students need more summer programming geared toward job readiness and occupational skills, plus a place for teens who have outgrown local recreation centers.

“I wake up in the morning, I’m 17 years old, I’m not working, I’m too old to go to the rec center, so what am I going to do?” Wilkins said. “We need more people that look like our students talking to our students having those conversations.”

Lancit would like to see more funding put toward the work the STEP program and others like it are doing. And both she and Wilkins would like more adults to come into schools and speak about the paths they have taken. “I think it’s good for them to be able to see that there’s plenty of Black and brown people that have come from where they come from that grow up and do amazing things,” Lancit said.

Youth experts suggest schools consider alternative resources for students like recreation sports, where they have a combination of physical activity and teammates, friends and coaches who are genuinely interested in their well-being. Coaches can also mentor students who may not have anyone to talk to at home.

MLK’s head football coach Malik Jones attended school with Hyneef’s father in the late 1990s and instantly developed a bond with the teen. “As soon as I knew that he was Bruce’s son, I had to just embrace him,” Jones said of Hyneef. “I showed him his dad in the yearbook. I mean literally every time I would see Hanif, he was a very affectionate kid and gave me a big hug.”

That strategy worked for Tyrell Mims, who was a star player for MLK’s football team under Jones. Mims, now a sophomore at Villanova University, credits the relationship with his coach for keeping him focused on the field and the classroom.

“A lot of kids that come to Martin Luther King come just for the four years just to be a student. The school brings in kids either from being in prison or coming from just a lot of rough backgrounds,” Mims said. “I never had my father in my life, but having Malik around was like the next best thing, like a good father figure in my life, somebody I could always talk to about things that’s not even related to football.”

If you are having trouble viewing this form on mobile, go here.